Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 2022-09-11 in all areas

-

From my point of view: Smurf problem is bc small community and small community is bc lag and bad game's performance. Everyone wants to play with known players and many "pros" seems to be afraid to play with "unknown" bc they don't know what his enemy would do. So the new ones can't play with those 40/50 good players and many times u have to wait 10/20 minutes or more to play. And many times, someone who was waiting so long to play its removed bc some balancing thing. In fact, "Smurf problem" it's just a matter for old players and big problem for a few "Zealots of the Balance". U always can ask to that "smurf" what lvl is and most of the time he'll answer. Ofc we all wants to play balanced games. But i think we are taking this to the extreme. We should think in ways to improve the game's performance, ways to make money, fund rising, buying coffes, idk but there's a group of ppl that works so hard to give us this RTS experience (The Best in the genre) and we should think better ways to help instead of asking those few devs to make some kind of anti smurf algorithm, wtf are we talking about?2 points

-

I propse the following idea: @user1 @Stan` @Dunedan To help moderators known players ( with their non smurf acccounts only) can be appointed "mod-helpers". They are able to vote for mod functions, such as "mute", "kick", "ban" for a certain player, and if a certain amount of of mod helpers, lets say 5 for example "vote" for such an action, the consequence will be enacted. It could be ofc limited to much less time as if mods do it. In the aftermath mods will be notified, and be able to check wether the action taken was "legit" or wether there was power abuse.2 points

-

before the animations tried to imitate humans feels... 1662872933604258.webm2 points

-

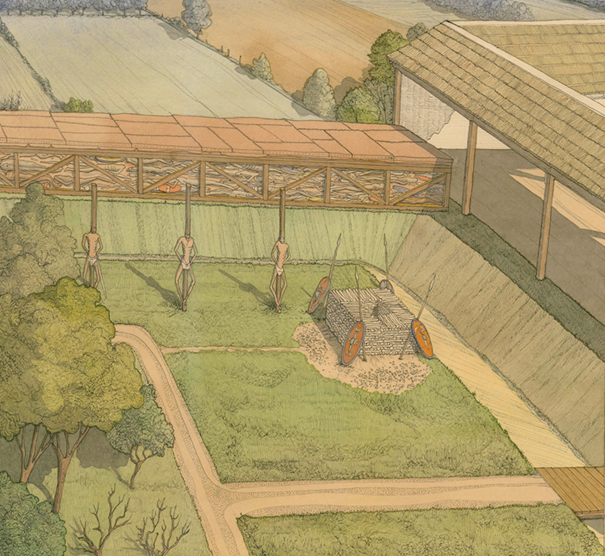

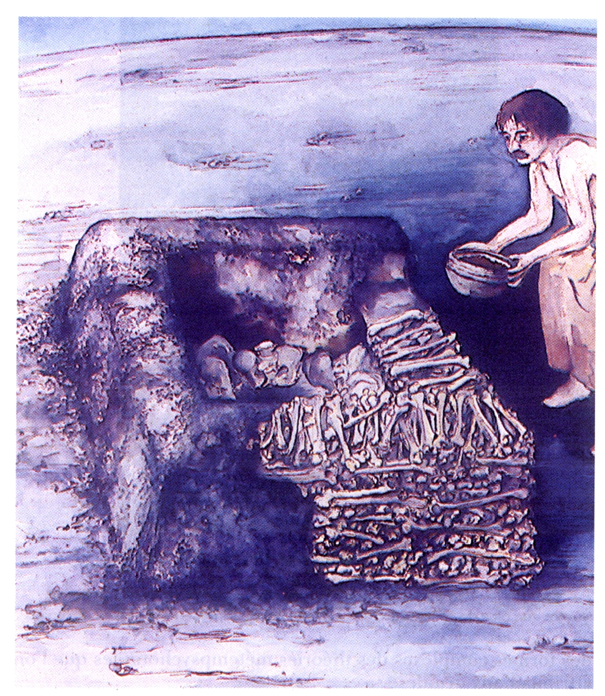

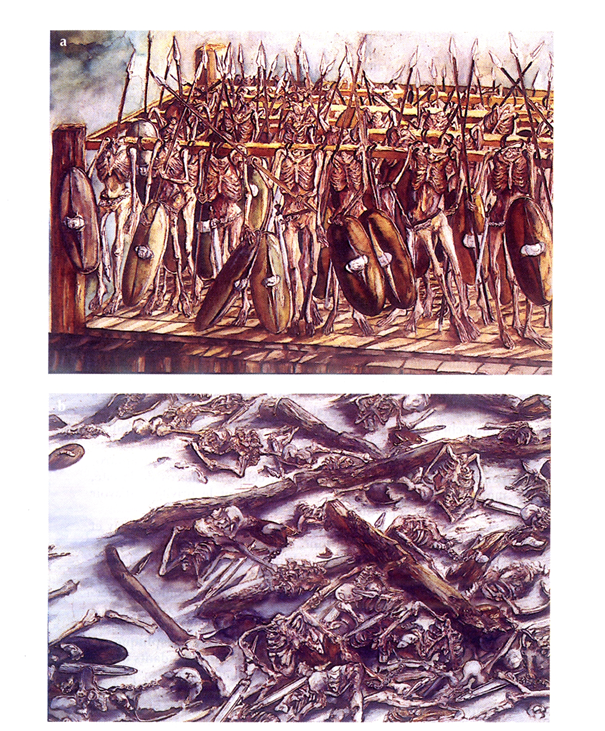

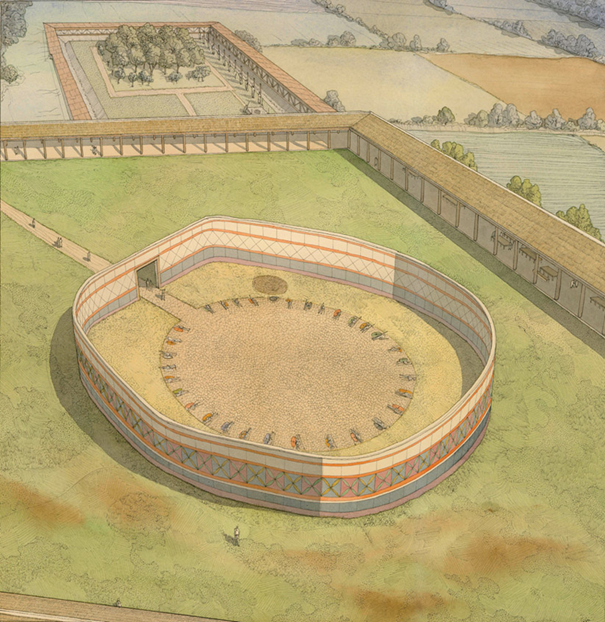

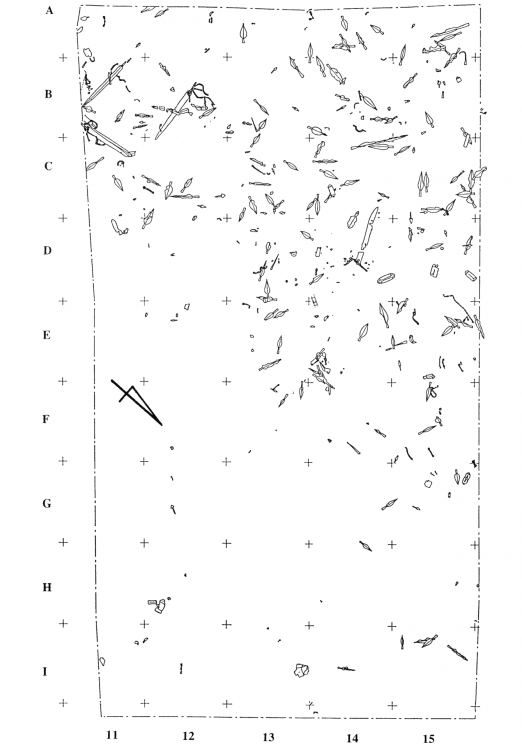

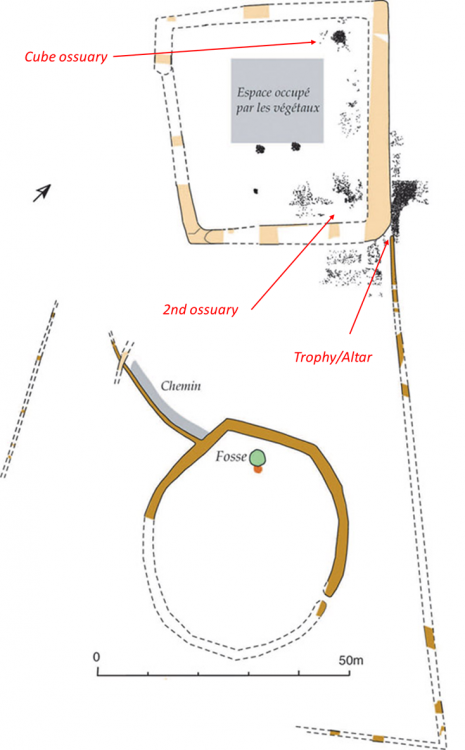

Religion is a matter of belief and rites, understood as a system of thoughts, of practices which found religious institutions and determine the function they perform in society. The relatively recent development of protohistoric archeology, in France as in most countries of Europe, has brought out from the subsoil an important body of documentation that simply did not exist 50 years ago. It will thus be difficult to find, in the sum of works and articles which were devoted to the religion of the Celts until the beginning of the 1990s, the slightest trace of sanctuaries, war trophies, sacrifices and banquets which founded and today structure our knowledge of religious practice in Gaul. The excavations at Gournay-sur-Aronde and Ribemont-sur-Ancre were revolutions in our perception of the religion of the ancient Celts. Many other places of worship and shrines have enriched our understanding of their society since then, but these two particular cases remain unique. Gournay-sur-Aronde is the better known and also the more presentable of these two examples. I will therefore present Ribemont-sur-Ancre first because it is really very interesting and fascinating. Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme department, Picardy, northern France) is significant because it reveals the existence of a forgotten battle, which was held in the middle of the 3rd century BC. Since the first exploration works done by archaeologists in 1966, Gallic weapons have been brought to light at the place of what was later recognised as a great monumental temple. They were then interpreted as burial remains later upset by the builders of the temple. We will see further that the encounter of Gallic objects and Gallo-Roman remnants on the same place is not due to coincidence but illustrates the story of a site used for nearly seven centuries. The discovery in 1982 of a strange set of human bones aroused more attention among archaeologists. It was composed of 2,000 bones coming from superior and inferior limbs which had been carefully lined up and crossed to form a kind of cube around a cylindrical cavity which contained burned splinters of human bone. It turned out that such a set had nothing to do with a funeral. More extensive research needed to be done. The bones found in 1982 Fifteen years of excavation were devoted to the study of these Iron Age levels. The topographical context provides interesting information. The place where the foundations of the great Gallo-Roman temple and Gallic remains were found is located in the valley of the river Ancre which flows into the river Somme about 15 km away. Its precise location is on a little hillock on the edge of the plateau. However, it is not situated at its top but slightly lower, on a slight slope which overlooks the valley. This area is actually an alluvial plain, perfectly flat and measuring 500 to 600 hectares. The Gallic site of Ribemont-sur-Ancre, later reoccupied by the great Gallo-Roman temple and its sacred surrounding wall, is located on the upper part, whereas the rest of the Gallo-Roman sanctuary (amphitheatre, thermal baths, residential area) go down in the valley to the river. This was the main motive for a careful archaeological survey of the place threatened by nearby construction projects. The Gallo-Roman temple The Gallo-Roman cult complex The site survey revealed the presence older enclosures nearby dating from the La Tène period, an Iron Age period in relation to the Gauls. Excavation revealed a very well-structured set of three enclosures which appears in the form of ditches and walls made of wood and cob. It is one of the characteristics of built areas in northern Gaul to be organized in such a manner. Agricultural domains, burial sites and fortified places are always quadrangular spaces bounded by more or less imposing ditches whose size corresponds to the nature of the built area. Circular enclosures are rarely found in the Middle and Late La Tène period. The three enclosures from the Iron Age These three enclosures differ architecturally. The square enclosure is bounded by an impressive ditch more than 2 m deep, remaining open, which is not doubled by a fence or a wall. The great trapezoidal enclosure consists of a wall made of wood and cob on which leans a portico on the inner side. The portico is composed of a roof resting on the wall and on posts in the front. The circular enclosure has the shape of a tower, closed by a thick wooden wall covered with cob, more than 6 m high. Inside these three spaces there was no building strictly speaking. But deposits of human bones and weapons allow us to imagine what the function of each of these spaces actually was. The quadrangular enclosure is just like one of the Gallic sanctuaries such as Gournay-sur-Aronde which were brought to light with accuracy for the first time in Picardy. It has the same plan and the same dimensions. The interior space is occupied by what seems to be a sacred wood, a grove about 20 metres wide. But it differs from it on important points: there is no altar in the shape of a large pit in the centre of the space, as it is always the case in sanctuaries. Here at Ribemont there are four altars of a different aspect located in each angle of the enclosure. These constructions were made of long human bones, forming something that looks like copings around little cylindrical wells. Of the four corners of the sacred space, only two were sufficiently preserved. In the eastern part, those who carried out the excavations unearthed a large pile of human bones, but in no recognizable order. But in the northern part they found what they called "the ossuary": an altar built of human bones - tibias, thighbones and humerus for the most part - measuring ~1.6 m on each side and with a height still preserved of 0.70 m. In the center of the altar was a hole, narrow and deep, which was filled with tiny pieces of burnt bone. This is the 2000 human long bones found in 1982, they were used for this construction. The rectangular enclosure is not closed by a thick wall isolating it from the secular world as sanctuaries usually are. Instead, there are strange constructions on the outer edge of the pit, on three sides: north, east and south. They are long wooden slatted cases (50 m long, 4 m wide and around 1.5 m high). They were full of human remains and weapons, set down with no apparent order. Finally, there is no monumental porch opening to the east: on the eastern side, common to the two quadrangular enclosures, the portico of the trapezoidal enclosure is used as a propylaeum. So it is certainly a sacred enclosure but it does not have the characteristic of sanctuaries. The lack of animal bones proves that sacrifices of domestic animals were not made. Reconstitution of a corner of the quadrangular enclosure with the ossuary Another reconstitution of the ossuary The mass grave, which is located in the eastern part of the quadrangular enclosure, is a deposit of 20,000 human bones that belong to more than 120 individuals, all male, young and rather tall. 300 pieces of weapons accompany them. The vast majority of the bones were found outside the enclosure, but some also on the other side of the ditch. But the skeletons, although found partially in anatomical order, were not complete. Many of the long bones were missing, and especially the skulls were missing. In this situation, one thinks of a process as follows: First, a crowd of beheaded warriors with their weapons were exposed on a platform elevated above the ditch. After their dismemberment, their long bones were used to erect the altars. The bones of the body were broken and burnt and finally put in the hole in the middle of the altar. Interpretation of the platform as a trophy and its degradation The trapezoidal enclosure, with the exception of the circular structure which is in its centre, revealed far fewer extensive archaeological remnants. They are also of a different nature. They are essentially animal bones, leftovers of food, and a few iron weapons discovered in a bad state of preservation. These remains were lying on the ground surface and therefore were badly preserved. They have to be related to the construction at the location where they were discovered. Porticos surrounding the wide space of the enclosure probably hosted men who shared meals. Such enclosures, significantly larger than the sanctuaries, were repeatedly discovered in the north and centre of the Gaul, and have the same characteristics. The circular construction in the centre of the previous space is the most unusual: in the Early La Tène period, the circular plan, used previously in necropolises, was no longer used. This laying out is strikingly monumental. It is a totally closed yard with an opening in the form of a small door made in the enclosure wall. The wall in wooden posts, covered with wattle and cob, was likely to be 6 m high. It was covered by a coat of clay, thinly smoothed and adorned with engravings. The interior of the space was almost empty. The remains of a paving made of sheets of flint were found there and, above all, a gigantic ditch, in every respect similar to hollow altars of sanctuaries. It contained extensive archaeological material: human remains of about 30 people, animal remains, ceramics and iron weapons. Similar material was found in the ditch of the foundations of the wall, where it was spilled, once the construction had been entirely and carefully taken down. The plan of the enclosure, as well as the material which was found in it, leads us to think that it had a funeral function. Reconstitution of the three enclosures in the landscape (not all elements are visible) This architectural complex at Ribemont is, at the present time, unique in the archaeological literature. It shows undeniable similarity with a well-identified laying out, composed of a sanctuary, an enclosure for banquets and a funeral enclosure. In spite of that, its general function is not obvious. We have to question the very specific archaeological material which was found there. It is composed, for the most part, of human remains (23,000 bones) and iron components (around 10,000) coming from weapons, elements of harness and of chariots. Animal bones and pieces of ceramics are much rarer than on any other contemporary site. They cannot be found anywhere in certain areas of the site. For example, in the square enclosure and at its periphery hardly any ceramics were found, and the animal bones are remains of horses which were treated in the same way as human bones. Both the nature and the dating of the metallic remnants show great homogeneity and coherence. Most of them are objects which date back to the Middle La Tène period. However, in the trapezoidal enclosure there were more recent objects (Late La Tène period) close to older finds. The state of the weapons is also significant. Generally, they do not present mutilations specific to offerings that can be observed in sanctuaries: they were not ritually bent or twisted. But they show traces of blows, undeniably caused by use, or during the battle in this case. The study of human bones gives even clearer information. All the remains belong exclusively to male individuals, more specifically young adults. Their size is rather tall as it corresponds to that of our contemporaries. At least 508 individuals have been determined, but the original number would have been much higher. Indeed, most human remains were not discovered in the form of entire skeletons but in fragments: chests, pelvises, limbs, hands, feet, necks, a lot of bones scattered here and there. No cranium was discovered. The cervical vertebrae discovered show that the heads were systematically cut off with a knife from the corpse not yet fully decomposed. An important number of bones bear marks of blows of different natures. These marks can be classified in two categories: those which were indubitably caused during a fight (blows of swords, impacts of spearheads, essentially) and those which are attributable to post-mortem dismemberment. There is no doubt that we are dealing with a warlike population. A selected human sample appears: young male adults, rather tall for that era, of strong constitution and well-fed. Not only were these men gathered together to make war, but it seems that it was their primary occupation: they were fed and supported for that and they didn’t have to achieve difficult tasks in the fields or in the craft industry. The weapons that were discovered near these warriors (sometimes still in a functional position on the remnants of the corpses) show they were actually used once. No attempt was made to repair them, which would have been possible. They also tell us the approximate time in which they were in use, around 260–250 BC. A few weapons from Ribemont-sur-Ancre The presence on the same place of such a large quantity of human remains and weapons can only be explained by a warlike event of a huge importance. What is striking is that the floor levels of the exterior border of the sacred enclosure which brought to light the large majority of these remains were preserved only on one tenth of their initial surface. Therefore, the number of human bones and weapons should be multiplied by eight or ten to have a better idea of the initial quantity of these remains. Consequently, the number of combatants could have included several thousands. This raises several questions: Where did this battle occur? Who were the belligerents? What were the causes for the conflict? The question of the localisation of the battlefield has been left unanswered up to now. But there are some elements. The first clues are given by the human remains. Their high quantity and above all the relatively well-preserved anatomical connection between the bones suggests that they could not have been carried over a long distance. Feet and hands still had their phalanxes, rib cages were still in place. Environmental studies carried out on the deposits of human bones and weapons tell us that the event occurred in the warm season, probably in summer (after the beginning of the harvest), at a time of the year when corpses could not be easily preserved. Remains of weapons and other accessories lead to the same conclusion: they were probably not moved over a long distance. The most realistic hypothesis is that the battle took place at the foot of the installations intended to commemorate it, i.e. on the vast alluvial plain lining the river Ancre on the west side. There, it was possible to develop a great battle front and above all to use fight chariots, hard to handle on an irregular ground with heavy slopes and on a muddy ground. The particularities of the sacred enclosure suggest that a part of its layout (the sacred wooded area) must have had a role in the way the winners conceived the battle. From this place it was possible to watch the fights, and they could imagine that gods protecting the people were settled down for a moment in the existing copse around which the sacred enclosure was built. The identity of the two opponents is revealed by the history of the place and by elements of the archaeological material. The great architectural complex built on the slope of the Ancre’s valley was intended to celebrate a victory which took place at the site itself, or very close to it. If the victors were not on their own territory, if they were invaders or if they got into their neighbours’ lands for a punitive war or a plundering operation, they would have been content with the building of a simple tropaion (a heap of weapons or a symbolic ephemeral building). The complete opposite occurred: a monumental and lasting building marked the place. Furthermore, it was regularly visited until the Roman conquest. So we can deduce that the very inhabitants of the place decided to erect this tropaion to commemorate the defence of their own territory. The name of this people is known thanks to Julius Caesar: they were called the Ambiani (Caesar, BG 2, 15, 2). This name was later given to the civitas which, in the 1st century BC, occupied the region whose centre was marked by the Somme valley. Thus the victors of this forgotten battle were the Ambiani themselves, or their ancestors, before they got this name. They may have formed a particular pagus of this civitas. A Gallo-Roman inscription discovered in front of the great Gallo-Roman temple of Ribemont mentions the name of the local population, although only the ending of the name – viciens – remains. The identity of their opponents is given by several gold coins. They were found among the remains amassed around the sacred space. These coins are all half staters or quarters of staters imitating the stater of Philipp II of Macedonia. Their origin is set in the west of France, in the region where the Aulerci Cenomani are said to have lived. So they prove that the defeated were strangers who had travelled 300 km to the northeast. It is obviously more difficult to ascertain the reasons which triggered the conflict. Nevertheless, a few pieces of historical information lead us to form a hypothesis. Caesar, on the basis of some information provided by the Remi, writes that the Belgae, a population which includes the Ambiani, came from Germanic territory and settled down in northern Gaul “antiquitus”, “in times past”, that is to say at a time previous to one that cannot be fixed precisely by human memory, thus two or three centuries before (Caesar, BG 2, 4, 1). Archaeological research confirms population movements in this area between the 5th and the 2nd centuries BC but on lesser distances than those suggested in Caesar’s text. It seems that these peoples stopped off during rather long periods, and that the first Belgic populations settled in the southernmost regions, as far as the Ile-de-France, while the last peoples had to content themselves with the northern regions. So the Ambiani may have arrived at the end of the 4th century BC or at the beginning of the 3rd century BC. That is also suggested by the pottery found in the circular building. It differs radically from the contemporary ceramics found farther south, for example among the Bellovaci, and presents, on the contrary, huge similarities with finds from the north and in particular from Belgium. It can be argued that the coming of a new population along the Channel and on each side of the river Somme, which was one of the commercial ways linking up the British Isles to the centre of the Gaul, overturned the political and economic balances of western Gaul. The Veneti and their Armorican allies had carried out commercial exchanges across the Channel for a long time. The coming of Belgae, many of whom had crossed the Channel to settle down in southern Britain, probably worked against the interest of the Armorican peoples. The high number of combatants excludes in any case the idea that it could have been a simple settling of scores on minor issues. Armoricans lost more than 500 of their men, or, in all likelihood, many more. The Ambiani, on their side, had to deplore only about 30 (minimum number identified) or, at the very most, about 50 dead. This ratio, which seems out of all proportion, is usual in antique battles. It seems that the army which was the first to surrender endured the biggest losses during the fight. It is possible that a large number of prisoners were added to the dead. For the Gauls the fight was similar to an ordeal or a sacrifice given to their gods. All the remains returned to them. The battlefield was carefully cleared of all that was lying on its surface. That is one of the main reasons for the difficulty in identifying the places of the battles of the last centuries BC, and this is exactly what Livy and Posidonius relate: The Gauls began systematically to cut off their enemies’ heads. It was the first gesture they carried out at the end of the battle (Livy, History of Rome, 23, 24; Diodorus Siculus, Historical Library, 5, 29, 4). According to Posidonius, it is likely that warriors, during the battle, proceeded to this gesture, at the risk of being killed by their enemies. The discoveries made at Ribemont confirm the technique of cutting off the heads described by these authors. All the heads were carefully cut off with a knife by those who were brave enough to become their owners. According to Livy, this operation took a long time: in the case held up as an example, it required a complete day. It was only later that the rest of the remains (acephalous corpses, weapons, horses and chariots) were collected. But that could not be done immediately. First, the place where these remains would be ultimately consecrated had to be carefully arranged. Meanwhile, it is possible that human remains and horse remains were gathered on the spot, so as to be protected by tarpaulin. Vultures and crows, since the beginning of the battle, had been watching out for their prey. Yet, the summer heat sped up their decomposition. If the bloody corpses – most often bearing wide open wounds – would had been attacked in addition by birds of prey, dogs and foxes, they would not have been transportable. As stated earlier, it was urgent to arrange the place that was to receive all the remains of the battlefield. Maybe this was done even before the beginning of the battle. The choice was a little wood in the middle of pastures and cultivated fields. The Ambiani army may have decided to settle down there to wait for the enemy. In any case, they had to draw the sacred space around this little wood before the time of the confrontation, maybe to accomplish a first religious ceremony in honour of the gods, so that they might give their support to the warriors. Indeed, the ditch surrounding the sacred space and the four cylindrical cavities had time to fill in lightly before the remains reached the place. It was necessary to build the repositories for the battle remains as quickly as possible. They were of two sorts: the first would receive the remains of the defeated enemies and the others those of the warriors of the victors. In the first case, long cases which were erected on the exterior side of the sacred enclosure. As they were not real victims sacrificed especially for the gods in their sanctuary, they were exposed outside the sacred space, exactly like the offerings that can be seen in contemporary Gallic sanctuaries, hanging on their walls outwardly. In this case, the quantity of the remains was so important that they actually constituted the enclosure of this space: there was no wall, but only boxes that marked the contours of the place. The remains of the Ambiani warriors deserved another treatment: they were the bodies of real heroes whose funerary treatment should match their status. That’s why the enclosure where they were to be deposited adopted a circular plan. Thanks to the poet Silius Italicus, we know that Gauls believed that the souls of warriors killed on the battlefield joined directly the celestial heaven if their bodies were eaten by scavenger birds (Silius Italicus, Punica, 3, 340–343). So this operation had to be done quickly and in the best conditions. This explains the very strange shape of the enclosure, the form of a high tower totally closed to the men and the terrestrial animals. It is plausible that the bodies of the 30 or 40 heroes that were carried to the place were set down in the enclosure on the paving, exposed to be eaten by birds and other animals. They were probably left in this state for a few weeks, until there was nothing left but bleached bones. The distribution of weapons and metal furniture in the charnier constituting the sacred trophy1 point

-

@Old RomanGood feedback, thank you! I've slowed down the pace of the stone and metal in the git version, so those changes will be included with the next release, which will probably happen within a week or two.1 point

-

Another winner Andy. I liked the pace set by the resource trickle instead of near limitless resources of deathmatch. The best part of course was the AI was a bit confused by what was going on. The existing army should certainly satisfy players looking for very quick games.1 point

-

1 point

-

Yeah, biomes need extended to make them allow for more stuff like this. It is a WIP tho.1 point

-

What I really experienced as positive about the AoE2 community on voobly, is that how easy it was to play with modded settings. If someone felt that there was a better way to generate the map, they would install the map and people joining the lobby would automatically download it and be able to play on it.1 point

-

1 point

-

another suggestion: add some boars to 1 or 2 mainland biomes. Some biomes just have deer.1 point

-

Is that screenshot made via F2 in the game? Could you try to switch to OpenGL backend? I also found the following quote from https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/gaming/game-bar/known-issues: So it might mean that the game bar might not work correctly on some drivers.1 point

-

suggestions for settings stuff: Allow the user to set scroll/rotate speed in the settings menu (currently this is done in game with a hotkey and resets every game) allow user to choose a resolution that fits their computer best.1 point

-

Grand temple of Amun can be used to make healers start at rank 3. Not so useful in a25 because of healers' behavior and the meatshield meta. In a26 I could see this becoming quite powerful for elephants, swordsmen, and archers that Kushites get. Also, it is a massive temple, which has the following benefits: 40 unit garrison space teleport distance is insane large hp1 point

-

Me with my score 1200 I played 1v1 with a person having a score almost 1500. I won, played a long game, defeated all units. He wasn't willing to resign and then he left just a minute before killing the last unit. Replay attached. So sorry to see such a behavior in the game :-( My nick: petiprg (1212), My opponent: auxilentmoon (1494). Thank you very much for your time! commands.txt metadata.json1 point

-

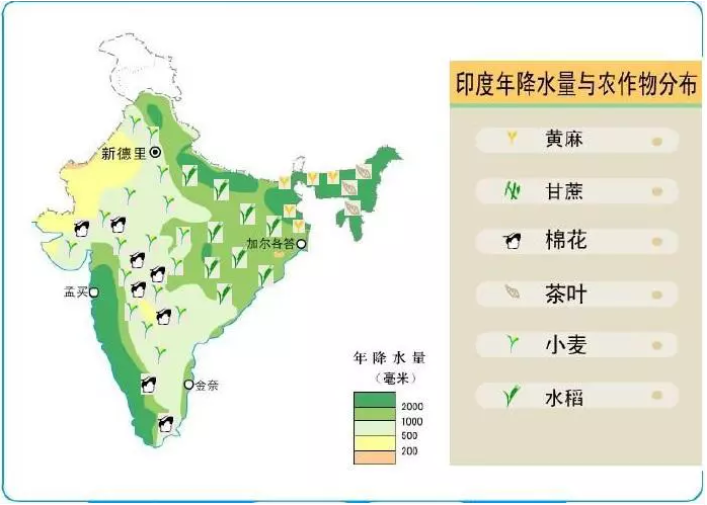

In fact, I also want to know whether the current Alpha 26 rice fields or the larger rice fields like the ones used by DE mod are suitable for Magadha? Indians also planted rice very early, and the core territory of Magadha is roughly the same as the distribution area of rice in Indian agriculture today, but I don’t know if the situation around 200 BC was the same as it is now.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I suppose the smurf score of an account could be based on IP address and player reports. Two brothers playing on the same connection would show up as smurf/dupe account but as long as no preemptive measures are taken I think it's fine. Would be nice to rate 2v2. Lag is a bit too much for 4v41 point

-

Perhaps an account creation date would be a good way to help players make their own judgments about smurfs. I was thinking the account info sheet could be expanded to help this.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)