-

Posts

2.428 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

87

Everything posted by Genava55

-

Some plankton are dropping, other are increasing, the trend is difficult to assess currently, most scientists are unsure of this publication and remain unconvinced because there is a sampling issue from the data. Most of the monitoring data are not continuous in time and in space. If you are interested, the impact of an afforestation of the Sahara is discussed here: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10584-009-9626-y.pdf https://www.nature.com/articles/srep46443

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Adding new factions to the game

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

But the problem is the same. Do you really think that the Aztec and the Mayans built windmills and treadwheel crane? Do you think they built siege workshops? Do you think that the unique tech of the Aztecs, Garland Wars, is historically accurate to give a +4 attack bonus to the infantry? These problems with historical accuracies is inherent to the core gameplay of the game. This is the same with 0AD, barracks are not something very common in ancient times. -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Adding new factions to the game

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

A lot of things do not make sense in Aoe2 and they still maintain these things (and people are approving) because it will break the balance if removed or altered. -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Adding new factions to the game

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

I agree. Adding civilization only to add civilization, without having a minimum of documentation about them can be problematic if a nitpicker like me appears. Joke aside, faction like the early Germans are tough to document correctly. But I think one day they need to be include to make the transition to the part II. Currently we should focus on those with enough documentation and on the current factions that are in an upgrading process (thanks to people like you). Anyway I don't see why it should be a problem. Most of the differences are cosmetics/esthetics. All the factions follows the same basis for the buildings and the units, so clearly to bring enough diversity, the game need to include a lot of factions. -

I use the SVN version but I have this that is appearing, is it normal ? The healers are very nice by the way There is still the wooden scabbard on the fanatics Edit: and do you want to keep the different shades for the bronze helmets? Because currently there is this issue only with the Celts and I am not sure it will be appreciated by the players:

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

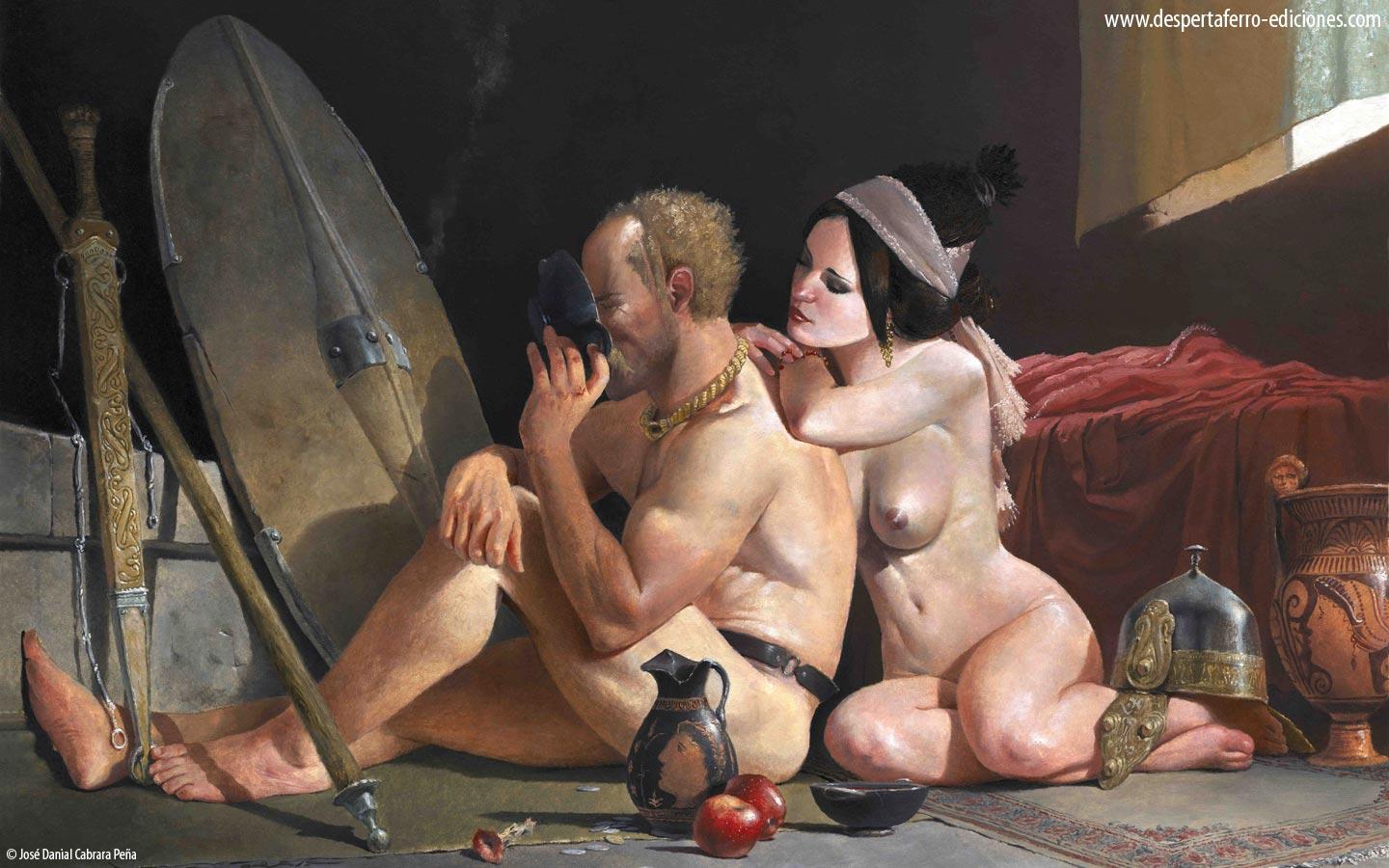

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

The Kingdom of Kush: A proper introduction [Illustrated]

Genava55 replied to Sundiata's topic in Official tasks

The Rosetta stone displays the word "Khopesh" (ḫpš) in Demotic Egyptian but the translations are inconsistent with "sword" in English and "Sichelschwert" in German. Sadly the Greek part is not helpful since they had translated it as ΟΠΛΟΝ (silly Greeks lol). Since the text is very religious and mythological, it is difficult to know if there are some outdated legacies inside. So it is not helpful. However, it seems on the wikitionary that the Greek word ξίφος (xíphos) could comes from the Egyptian zefet (zft), which has continued in Demotic Egyptian as sefy (sfy), which designate both a knife and a straight sword.- 1.042 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- civ profile

- history

- (and 5 more)

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

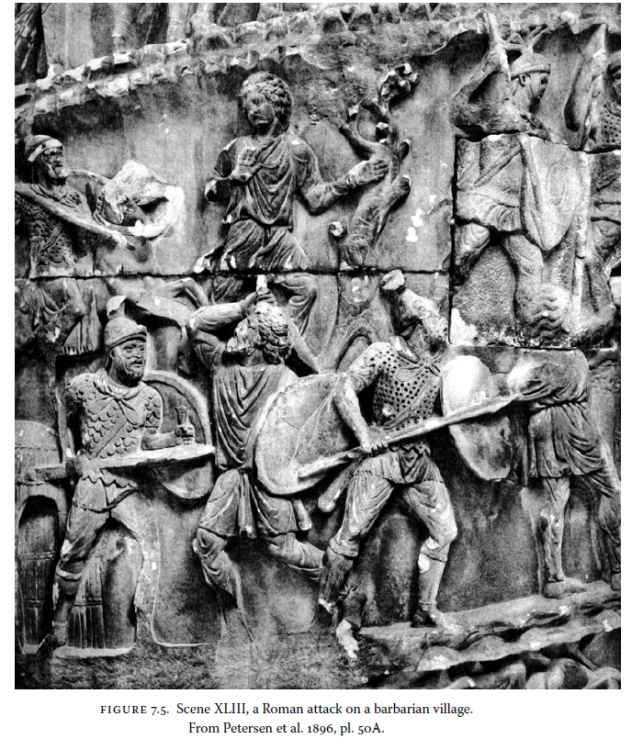

Arminius (*Herminaz?) could have Roman equipment from his past (Arminius is actually Cherusci but I think everybody wants him to be a playable hero, the other possibility is Maroboduus which is more accurate and more interesting). Ariovistus (*Harjafristaz? or a Celtic, Ariouistos?) could have Gallic equipment. Ballomar could wear a 100% Germanic outfit and carrying only Germanic weapons. Edit: Maroboduus could increase the experience gained by his troops as a reflection of the regular training he ordered. Ariovistus could give a territory extension bonus or a capture bonus as a reflection of his conquest in Gaul and his skills in politics. Ballomar could give a bonus in looting. -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

Sadly, there is absolutely no such thing as common armor for the Suebians. Neither helmets or chainmail were common, even in noble burials. Scale armor are only found in Roman auxiliary tombstone gravure. For the 3rd century AD, there is a chain mail found in Vimose https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-early-iron-age/the-weapon-deposit-from-vimose/the-chain-mail-from-vimose/ -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

A mod for M2TW -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

More: https://imgur.com/a/3bG69 -

Totally right.

-

That's a problem. I wonder if anyone did a comparative analysis of the civilizations before to design the factions. Clearly, the Celts are not economically better than the Greeks, the Romans or the Persians.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

The Kingdom of Kush: A proper introduction [Illustrated]

Genava55 replied to Sundiata's topic in Official tasks

- 1.042 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- civ profile

- history

- (and 5 more)

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

The Kingdom of Kush: A proper introduction [Illustrated]

Genava55 replied to Sundiata's topic in Official tasks

For me, indeed the butt-spike looks more like a sarissa-type than a dory-type. However, I found suspicious that nobody clearly expressed their use of the phalanx. Maybe it is only a long spear like in the case of the Cherusci. Since the Kushite faction has already a very diverse roster, maybe the pikemen can be moved to a champion unit or to a reform to research by the player as suggested by Sundiata.- 1.042 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- civ profile

- history

- (and 5 more)

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

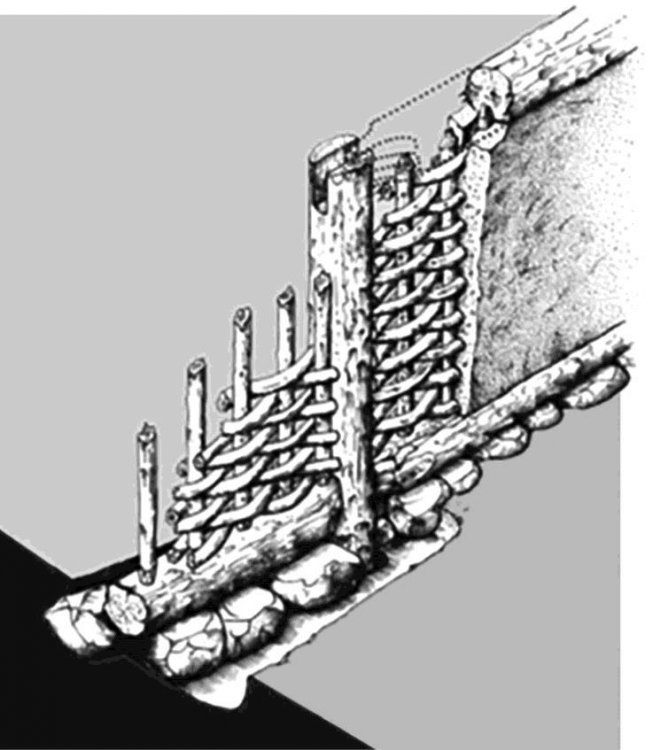

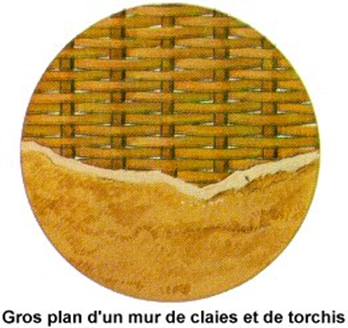

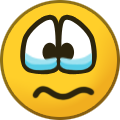

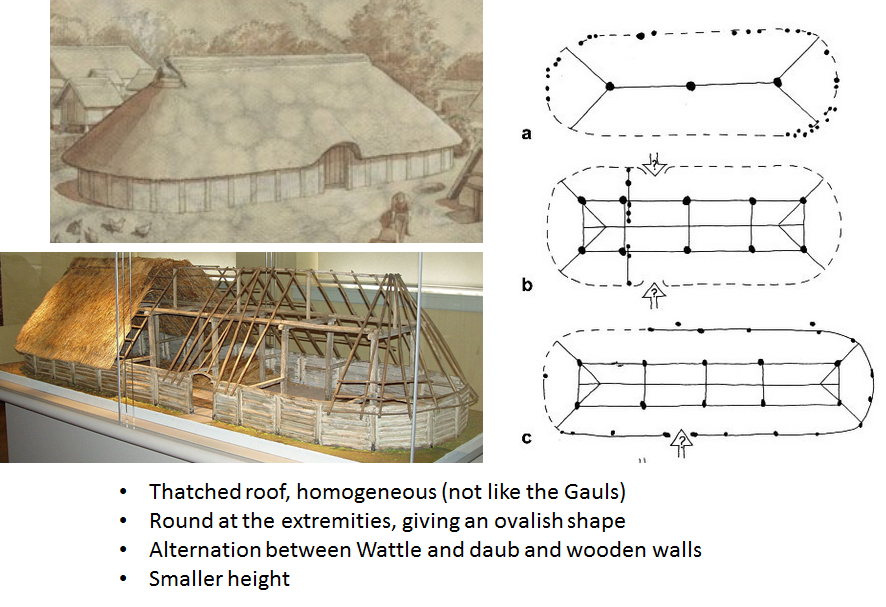

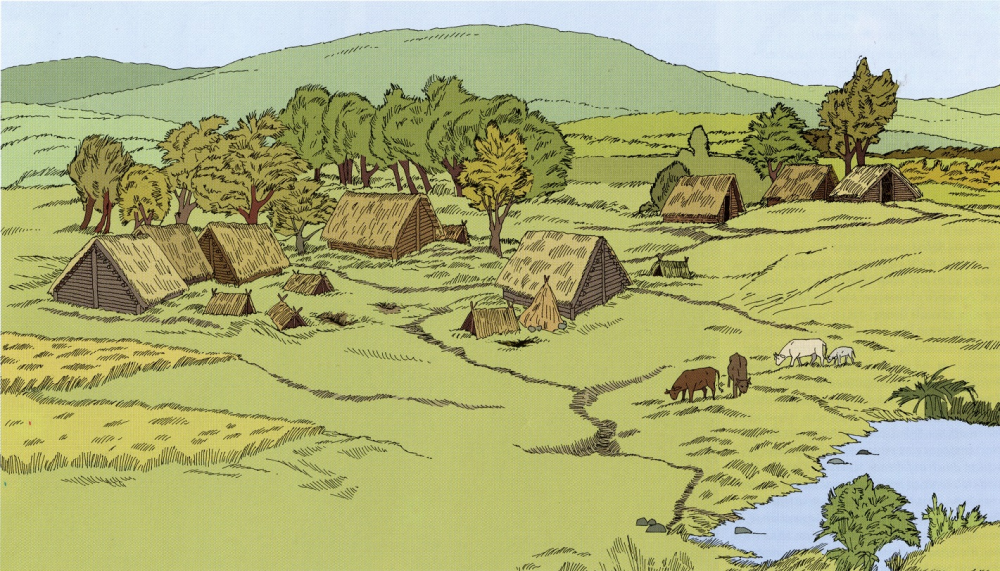

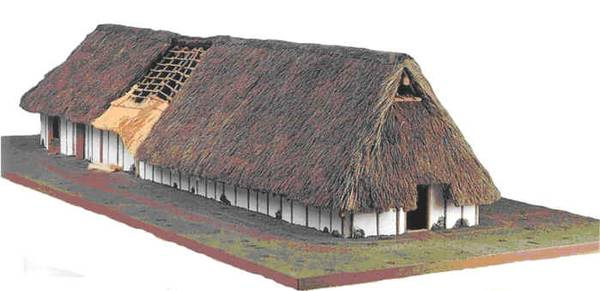

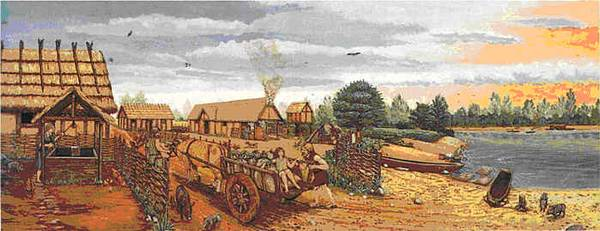

This kind of architecture could be perfect for later Germans like the Goths: While for the Early Germans like the Suebians, an example for the houses: Idea for a fortress: -

- 33 replies

-

- 1

-

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

Ok, so we could include some late architecture for this faction, notably as last phase buildings. https://elpais.com/elpais/2019/01/29/inenglish/1548751265_273108.html https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/reccopolis-revealed-the-first-geomagnetic-mapping-of-the-early-medieval-visigothic-royal-town/77961BE80B56E7F85F06F516B0E8C4C9/core-reader -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

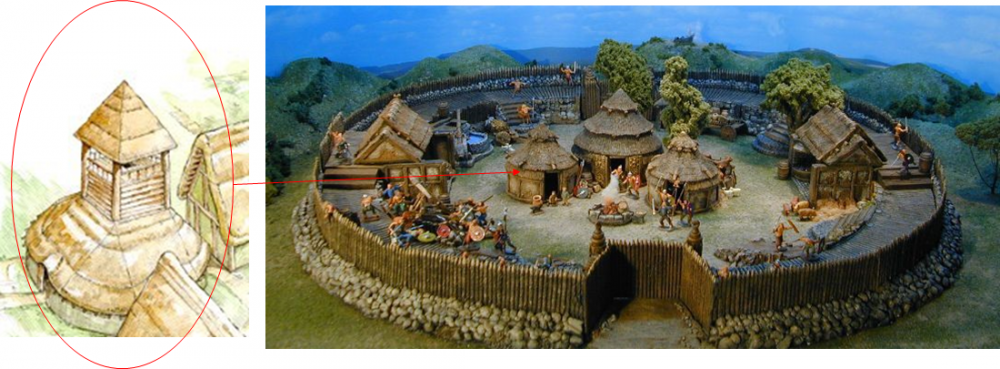

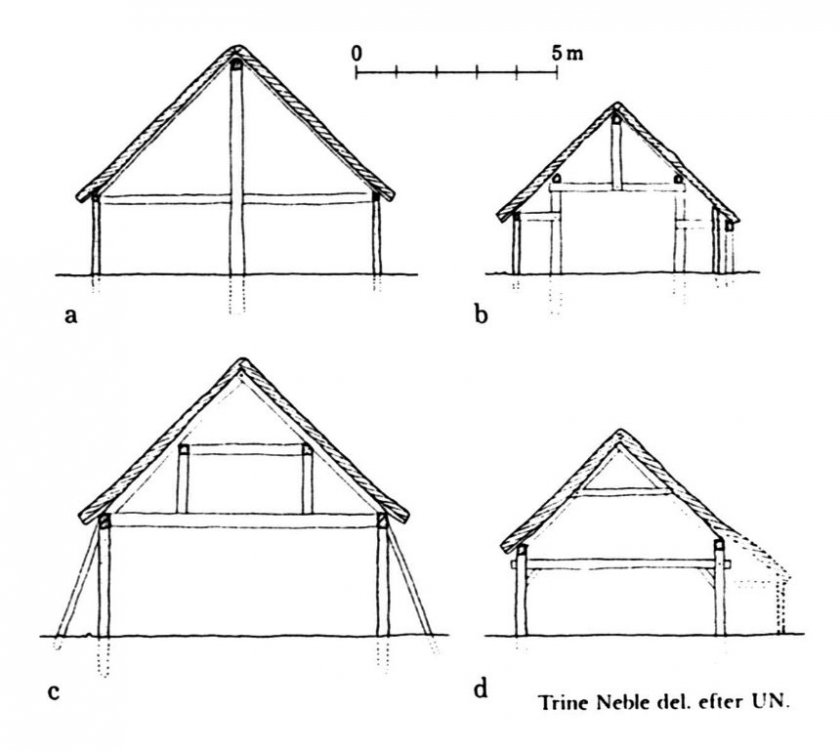

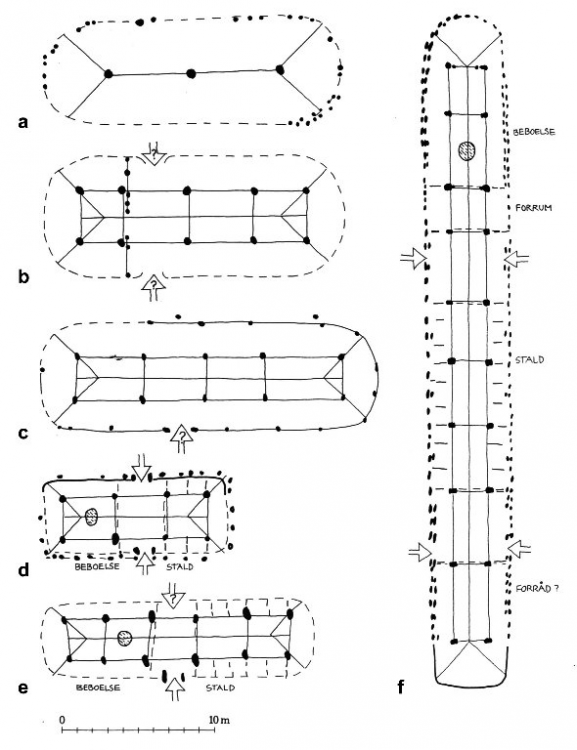

Fig 1. Excavation plan of a Migration period house at Lojsta (Gotland) and elevation of the reconstructed entrance wall and cross-sections at the second and fifth trestle from the entrance (after Boethius & Nihlén 1932) Fig 2. Sketched cross-sections of Danish house types, a: a two-aisled Neolithic/Early Bronze Age house; b: a three-aisled Early Iron Age house; c: a Viking Trelleborg house; d: a single-aisled Late Viking/Early medieval house with a lean-to added (after Näsman 1987) Fig 8 abcdef. Sketch plans of Danish houses: a; Neolithic - Early Bronze Age; b: Early Bronze Age; c: Late Bronze Age; d: Celtic Iron Age; e: Early Roman Iron Age; f: Late Roman - Early Germanic Iron Age. Tie beams, purlins and central ridges are drawn with unbroken lines. Hipped roofs are marked with an angle at the trestles at the end walls. Room divisions and stalls in byres are marked with broken lines where probable. Probable or certain fireplaces are marked by hatched spots (after Näsman 1987) -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

@wowgetoffyourcellphone Do you want to include the Visigothic Kingdom inside the Goths faction? -

If the Thracians are included as a faction, it will be centered on the Odrysian Kingdom. There is enough material to have a quite diverse faction, with a few unique weapons.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

Why not but it is exactly what is done for the Celts. But anyway, even a full set of thatched roofs could be different from the Gauls. The color and the texture can vary Illustrations, models and pictures from the Alamannen-Museum (4 and 5th century AD): Feddersen Wierde https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feddersen_Wierde https://www.burg-bederkesa.de/archaeologie-im-museum/feddersen-wierde/ Franks - Wohn-Stall-Haus aus Bielefeld, Archäologie-Museum Münster http://www.ingelheimer-geschichte.de/index.php?id=148 Reconstruction of a gothic long farm house near Masłomęcz am Hrubieszów (2nd / 3rd century) http://www.wioska-gotow.pl/ Vandalen settlement (4th C. AD) Thuringia