-

Posts

2.440 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

87

Everything posted by Genava55

-

It is indeed quite difficult to find exact equivalents for village, town, and city in Proto-Germanic, but Wufila's Bible is a truly incredible resource for this, as he had to translate many Greek terms into Gothic so that they would be understandable to the Goths. In Wufila's Bible, there is a sort of hierarchy with Haims < Weihs < Baurgs. Haim- is used for villages and hamlets. To designate less densely populated rural communities. A few examples: Mark 6:36 : ...galeiþandans in bisitandans haimos jah weihsa... / ...that they go to the surrounding countryside and villages... Mark 5:14 : ...gataihun in baurg jah in haimom. / ...they announced it in the city and in the countryside. John 7:42 : ...us Beþlaiaim þamma haima... / ... from the village of Bethlehem... Luke 19:30 : ...in þo wiþrawairþon haim.../ ...in the village across the way... Mark 8:27 : ...in haimos Kaisarias þais Filippaus. / ...in the villages of Caesarea Philippi. The issue with Þaurp is that it is mentioned only a single time in a fragment of the Old Testament in Gothic (Codex Ambrosianus D) and it can only mean in this case 'farmland' or 'estate' because it is used for Nehemiah 5:16. It cannot refer to a village or a hamlet.

-

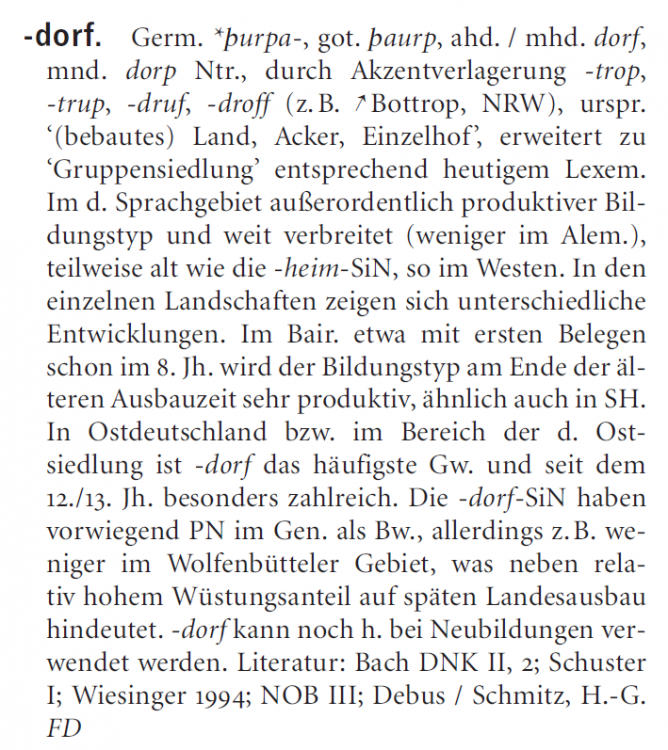

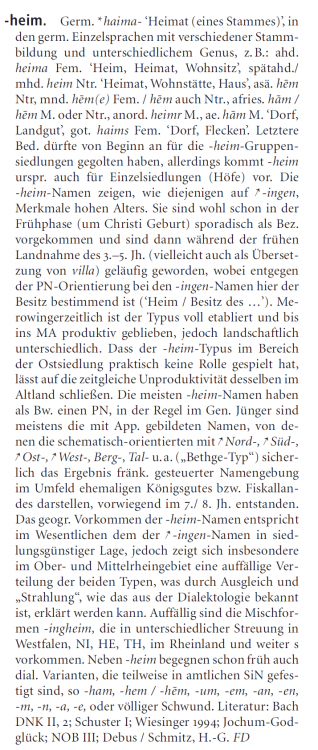

The original Latin text is the following: "Nullas Germanorum populis urbes habitari satis notum est, ne pati quidem inter se iunctas sedes. Colunt discreti ac diversi, ut fons, ut campus, ut nemus placuit. Vicos locant non in nostrum morem conexis et cohaerentibus aedificiis: suam quisque domum spatio circumdat, sive adversus casus ignis remedium sive inscitia aedificandi." Note that he uses the word "vicos" (accusative plural of vicus). So for him, they are like vici, not like villae, aedes, casae or domus. If these were truly isolated, solitary farmsteads miles apart from one another, the word vicus would actually be quite misleading. By choosing this terminology, Tacitus is making a specific point about the Germanic social structure. He describes dwellings that form local communities. Here is why he uses that specific term even if the houses don't touch. In fact, it doesn't really matter whether the buildings are close to each other or not. The real question is whether it is a territorial unit. Consequently, did the Germanic peoples give a name to this group of buildings? I think so. And I think that the word *haima- is more appropriate in this case. Because it is a terminology that can be applied to a family, a clan, or a tribe. I am reposting the description from the Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch (2017): -heim (page 254) -heim. Germ. *haima- ‘Home of a tribe’ (Heimat) ; in the individual Germanic languages with various stem formations and genders, e.g.: OHG heima Fem. ‘Home, homeland, residence’, late OHG/MHG heim Neutr. ‘Homeland, dwelling place, house’, OSax. hēm Neutr., MLG hēm(e) Fem. / hēm also Neutr., OFris. hām / hēm Masc. or Neutr., ON heimr Masc., OE hām Masc. ‘Village, estate’, Goth. haims Fem. ‘Village, small town’. The latter meaning likely applied from the beginning to -heim group settlements, although -heim originally occurred for individual settlements (farmsteads) as well. The -heim names, like those ending in -ingen, show characteristics of great age. They likely occurred sporadically as designations as early as the early phase (around the birth of Christ) and then became common during the early land acquisition (frühn Landnahme) of the 3rd–5th centuries (perhaps also as a translation of the Latin villa). In contrast to the PN-orientation (personal name) of -ingen names, the defining factor here is possession (‘Home / Estate of ...’). By the Merovingian period, the type was fully established and remained productive until the Middle Ages (MA), though varying by region. The fact that the -heim type played practically no role in the area of the Ostsiedlung (Eastern settlement) suggests its simultaneous unproductivity in the Altland (ancient lands). Most -heim names have a PN as the specific element (Bw.), usually in the genitive case. Younger names are mostly those formed with appellatives (common nouns), of which the schematically oriented ones with Nord-, Süd-, Ost-, West-, Berg-, Tal-, etc. (“Bethge-type”) certainly represent the result of Frankish-controlled naming in the vicinity of former royal estates or fisks; these predominantly arose in the 7th/8th centuries. The geographical occurrence of -heim names essentially corresponds to that of -ingen names in locations favorable for settlement; however, a striking distribution of the two types is evident particularly in the Upper and Middle Rhine regions, which can be explained by "compensation" and "radiation," as is known from dialectology. Notable are the mixed forms -ingheim, which occur with varying distribution in Westphalia, Lower Saxony (NI), Hesse (HE), Thuringia (TH), in the Rhineland, and further south. In addition to -heim, dialectal variants are encountered early on, some of which are fixed in official settlement names (SiN), such as -ham, -hem / -hēm, -um, -em, -an, -en, -m, -n, -a, -e, or total loss (elision). Literature: Bach DNK II, 2; Schuster I; Wiesinger 1994; Jochum-Godglück; NOB III; Debus / Schmitz, H.-G. FD There are two Gothic 'weihs' in the Gothic bible. One is used for 'holy' and 'saint' while the other one is used for village. But in this case it translates the Greek kōmē (Marc 8:23). It is a word with only a few mentions (with this meaning). The only reason I chose it as my second choice is that it seems to have been used much later, in the early Middle Ages, to refer in some cases to small Roman towns. Settlements which were more urbanized than the usual Germanic settlement. Anyway, it is also interesting because it is already mentioned in Gothic with a meaning that designates a kind of settlement, which is 4 centuries earlier than the later evidences. In Gothic bible, it seems Weihs was larger than Haims. My point of view is mainly to take a critical approach to linguistic reconstructions. These reconstructions are based solely on phonological rules and sound laws. A reconstruction is not a semantic analysis. That's why I prefer words that are closer chronologically. And the Gothic Bible provides an excellent case study for semantic analysis. Here what the Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch (2017) says about it: -wik / -wiek (page 692): Old Saxon wīk ‘dwelling, village’, Middle Low German wīk ‘place, settlement, (sea) bay’, Old/Middle High German wīch (masculine) ‘residence, city’ has been a subject of controversial debate regarding its origin and meaning. While older research assumed a loanword from Latin vīcus (‘quarter / city district, farmstead, manor, hamlet’) or assumed the meaning ‘trading/market place’ based on the North Germanic vīk (‘bay’), wīk has more recently been traced back to a Germanic word related to the same root as Latin vīcus, with the original meaning of ‘fence.’ This meaning evolved further in various contexts, for example, to ‘manor’ or ‘small settlement,’ and eventually to ‘district with special legal status or immunity’ (linked to terms like wikbelde / -greve). -wīk names are encountered in: Nordic countries and England; Particularly in the Dutch-Flemish region; In the Lower Saxon-Westphalian area (e.g., Braunschweig, NI); In Schleswig-Holstein (e.g., Schleswig; Wyk auf Föhr, District of Nordfriesland). This formation type likely dates back to the period of land development (Landesausbau) in its productive phase; in the Western Netherlands, it remained active until the 12th/13th century. Literature: Bach DNK II, 2; Schütte 1976; Debus / Schmitz, H.-G. FD

-

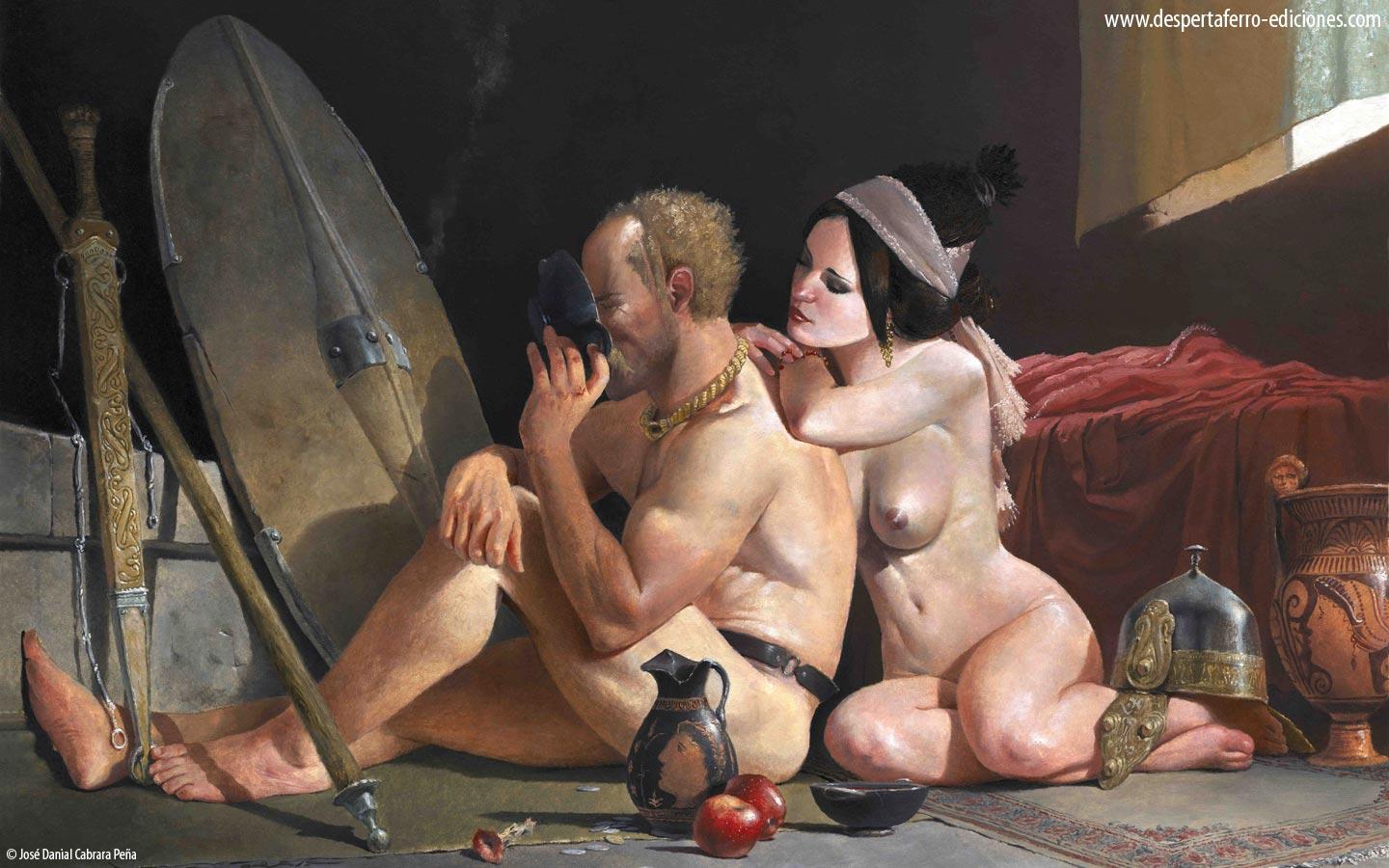

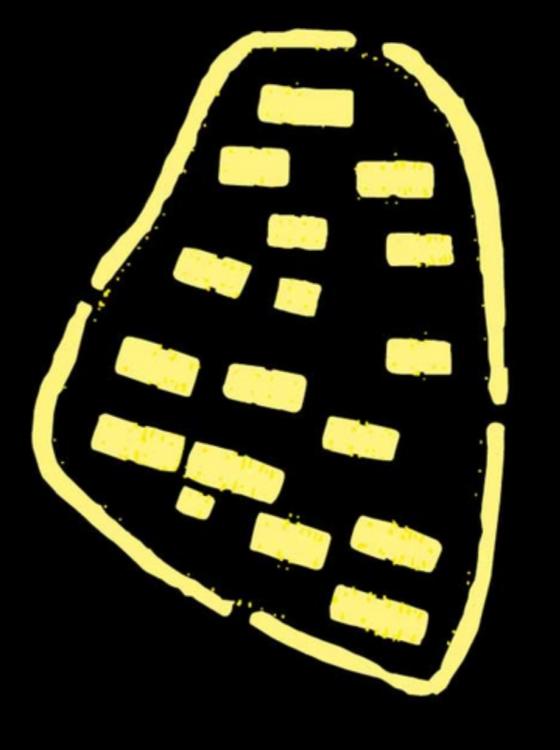

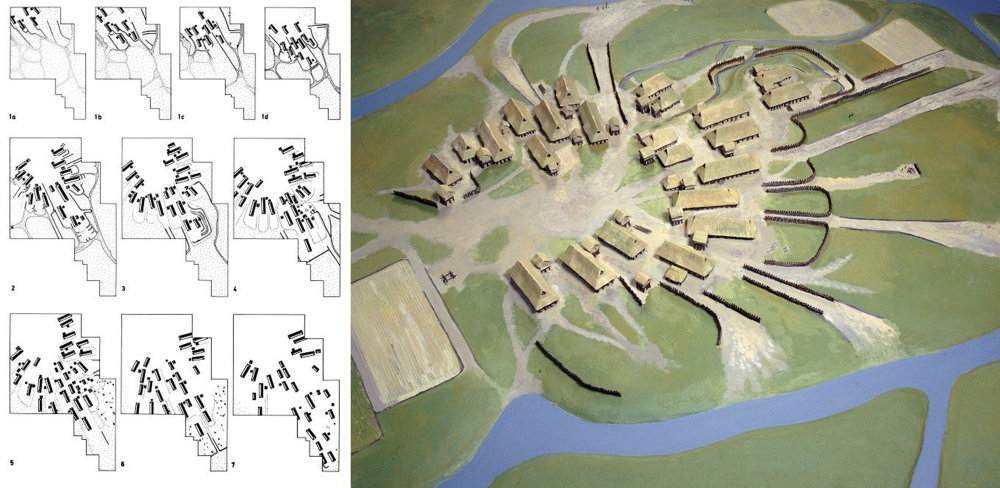

Ground plan for the village of Grøntoft in its last year. Grøntoft existed from around 450 to 150 BC. For most of the period it comprised of 12-20 buildings and accommodated around 50 people and 70-80 animals: Aerial photo of the fortified settlement in Borremose, Himmerland. Borremose is known for and identified with a former fortified settlement dating from the Pre-Roman Iron Age (400-100 BC). It was constructed during the 4th century BC, as one of the largest structures of its kind in Northern Europe, but was already abandoned during the 2nd century BC, when the houses were burned down and the whole site levelled to the ground. A plan showing the fortified settlement Lyngsmose, Ringkøbing. The rectangular houses are protected by a moat. There had been 15 long houses and two small houses. It is believed that around 8-10 people lived in each house, which means that there were around 120-150 people living in the village. The settlement was occupied between the 3rd century BC and the 1st century AD. Reconstruction of the Iron Age village of Hodde, which was located between Varde and Grindsted. As can be seen, Hodde was somewhat larger than Grøntoft. At its greatest extent it included 22 farms, blacksmiths and potters workshops. The village Hodde existed in the last century before the birth of Christ. It was a large village; at its peak, it included 27 farms with 53 houses and 200 to 300 inhabitants. Each farm was surrounded by a fence and the whole village was surrounded by a palisade as high as a person. Feddersen Wierde is an ancient terp settlement in Wremen (Lower Saxony, Germany), model displayed in the museum Burg Bederkesa. It was inhabitated from the 1st century BC to the 5th century AD. The village was built on a terp (artificial mound for flood protection), with multiple farms and longhouses evolving towards a hierarchical structure (central chief's house). Traces of collective dwellings, agriculture and livestock farming across several phases. But thanks for the effort. I think that if a linguistic dictionary said that the ancient Germanic peoples traveled on camels, you would believe it without hesitation.

-

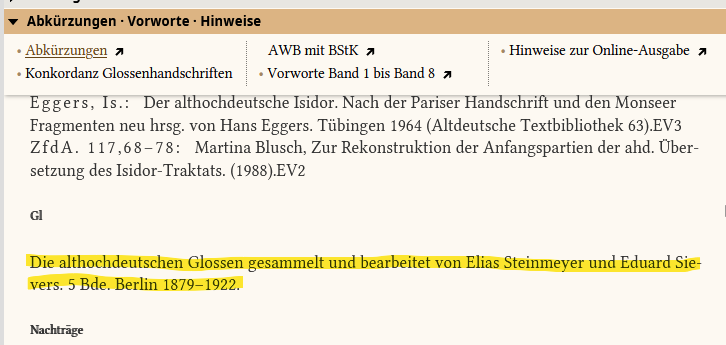

You don't seem to understand the abbreviation. Gl stands for Die althochdeutschen Glossen gesammelt und bearbeitet von Elias Steinmeyer und Eduard Sievers. 5 Bde. Berlin 1879–1922. For example Gl 1,242,35 means Volume 1 page 242, line 35... So once again you are arguing without knowing and without checking your info. Definition 1 uses Gl 1,242,35 which is the "Codex Sangallensis 911" from the 8th century AD. Definition 2 uses Gl 3,16,51 which is the "Codex Sangallensis 242" dated between the 9th to 10th century AD. Definition 2 uses Gl 3,209,19 which is from a version of the Summarium Heinrici dated to the 11th century AD. It should be noted that I had to go to the library and consult several encyclopedias to find these references. I would really appreciate it if you would make an effort before arguing from now on. It is important to understand that the "Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch" dictionary has a strict classification system and that the order of definitions for the same word follows a precise logic. The primary meanings are generally the oldest and/or most frequent. The aim is to provide a practical reading experience and to understand the evolution and diversification of meanings. This dictionary truly emphasizes this aspect and is known for its quality in this regard. Once again, I am right. The primary meaning in Old High German is indeed that of a farm or agricultural estate. It was the original meaning. I know I may sound like I'm defending something weird that nobody talks about, but it's actually something well-known in German when you're interested in the study of place names. Let's take a recent source on the subject, Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch (2017) by Manfred Niemeyer. On page 133, there is an entry for place names ending in -dorf. Here my translation: -dorf. Germ. *þurpa-, Goth. þaurp, OHG / MHG dorf, MLG dorp Neutr.; through metathesis (accent shift) -trop, -trup, -druf, -droff (e.g., Bottrop, NRW). Originally ‘(cultivated) land, field, isolated farmstead’, later extended to ‘group settlement’ in accordance with the modern lexeme. Within the German-speaking area, it is an extremely productive formation type and widely distributed (though less frequent in Alemannic); in the West, some instances are as old as the -heim settlement names (SN). Different developments can be seen in the individual regions. In Bavaria, for example, with the first evidence dating back to the 8th century, the type became highly productive at the end of the older expansion period (älteren Ausbauzeit). In Schleswig-Holstein there was also a similar pattern. In Eastern Germany, in the areas of the medieval Ostsiedlung (Eastern settlement), -dorf is the most frequent generic element (Gw.) and is particularly numerous since the 12th/13th century. The -dorf settlement names predominantly feature personal names (PN) in the genitive case as their specific element (Bw.). However, this is less common in the Wolfenbüttel region, for example; this fact, combined with a relatively high proportion of abandoned settlements (Wüstungen), points toward a late period of land development. -dorf can still be used today for new formations. I'm not making this up, it's something that's already known. No problem with that, I recognize that Old Saxon and Old English have kept mostly the collective meaning (village or hamlet). My point is that Gothic, which is oldest, only has the first meaning, as farmstead or farmland. You suggested that the Gothic language might be the one that deviated from its original meaning (this is already not very intuitive and rather inconsistent with what we generally observe in linguistics for the direction of the shift). I am disagreeing on this. And as I said, Old High German uses the first meaning in the oldest records. For me it is quite obvious that this is a change of meaning which is taking place at the beginning of the Middle Ages and which is not yet universal in all Germanic languages. There is also an interesting aspect to Old Norse þorp, a semantic analysis shows that it generally refers to a secondary or dependent hamlet, such as an isolated farm or a hamlet subordinate to a larger main village. Old Norse seems to have captured a different shift from Old English. But again, for me this is further evidence that this was a process underway during the early Middle Ages. The concept of home is not that simple and you are taking its historical dimensions too lightly. See the concept of Heimat for example, which is very difficult to translate in other languages. You seem to have a modern perception of the concept of home. I am just saying that during the pre-Roman Iron Age, this is a very different situation. Archaeologically, we observe the proximity of different families under the same roof. On the topic there are two interesting work: Adolf Bach, "Deutsche Namenkunde" (several volumes, 1952-1956). Bach explicitly categorizes -heim names as representing the oldest layer of communal village foundations (the Urdörfer). Henning Kaufmann, "Die Namen der rheinischen Städte" (1973). Here Kaufmann discusses how names like Mannheim or Bad Dürkheim reflect the Frankish Landnahme (land-taking), where a leader established a collective settlement for his entire retinue. But since they are old studies, I can simply cite the Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch (2017): Mannheim (page 390) III. It is a compound (Zuss.) with the generic element (Gw.) -heim; the specific element (Bw.) is based on the personal name (PN) Manno: ‘Settlement of Manno’. The dialect form Manm is likely influenced by the demonym (inhabitant name) Mannemer. -heim (page 254) -heim. Germ. *haima- ‘Home of a tribe’ (Heimat) ; in the individual Germanic languages with various stem formations and genders, e.g.: OHG heima Fem. ‘Home, homeland, residence’, late OHG/MHG heim Neutr. ‘Homeland, dwelling place, house’, OSax. hēm Neutr., MLG hēm(e) Fem. / hēm also Neutr., OFris. hām / hēm Masc. or Neutr., ON heimr Masc., OE hām Masc. ‘Village, estate’, Goth. haims Fem. ‘Village, small town’. The latter meaning likely applied from the beginning to -heim group settlements, although -heim originally occurred for individual settlements (farmsteads) as well. The -heim names, like those ending in -ingen, show characteristics of great age. They likely occurred sporadically as designations as early as the early phase (around the birth of Christ) and then became common during the early land acquisition (frühn Landnahme) of the 3rd–5th centuries (perhaps also as a translation of the Latin villa). In contrast to the PN-orientation (personal name) of -ingen names, the defining factor here is possession (‘Home / Estate of ...’). By the Merovingian period, the type was fully established and remained productive until the Middle Ages (MA), though varying by region. The fact that the -heim type played practically no role in the area of the Ostsiedlung (Eastern settlement) suggests its simultaneous unproductivity in the Altland (ancient lands). Most -heim names have a PN as the specific element (Bw.), usually in the genitive case. Younger names are mostly those formed with appellatives (common nouns), of which the schematically oriented ones with Nord-, Süd-, Ost-, West-, Berg-, Tal-, etc. (“Bethge-type”) certainly represent the result of Frankish-controlled naming in the vicinity of former royal estates or fisks; these predominantly arose in the 7th/8th centuries. The geographical occurrence of -heim names essentially corresponds to that of -ingen names in locations favorable for settlement; however, a striking distribution of the two types is evident particularly in the Upper and Middle Rhine regions, which can be explained by "compensation" and "radiation," as is known from dialectology. Notable are the mixed forms -ingheim, which occur with varying distribution in Westphalia, Lower Saxony (NI), Hesse (HE), Thuringia (TH), in the Rhineland, and further south. In addition to -heim, dialectal variants are encountered early on, some of which are fixed in official settlement names (SiN), such as -ham, -hem / -hēm, -um, -em, -an, -en, -m, -n, -a, -e, or total loss (elision). Literature: Bach DNK II, 2; Schuster I; Wiesinger 1994; Jochum-Godglück; NOB III; Debus / Schmitz, H.-G. FD In your opinion it doesn’t originally refer to a settlement, but that's the case for many linguists. I am doing it right now. Just consider the Brandolini's law and the time it takes to refute something. Here I took the time to construct a coherent and well-sourced argument.

-

This debate will never end, so what do you suggest? I am skeptical about *þurpą meaning village that early on. You are skeptical that *haimaz means village that early on. Is there an alternative?

-

See this lexicum : https://awb.saw-leipzig.de/?sigle=AWB&lemid=D01106 It seems clear in the case of Old High German that farmstead and farmland are the first meaning. And it is even clearer that Old High German retained different meaning and different expression related to this root suggesting a general shift from the singular to the collection. The direction of the change is obviously from a singular farmstead to a collection. The entry breaks down the definition into four distinct historical layers: 1. The Estate or Farmstead (Hof, Landgut) In this earliest sense, thorf refers to private property—essentially a "manor" or a "ranch." a) The Reluctant Guest: One citation describes a man excusing himself from a banquet: "thorph coufta ih... inti gisehen iz" ("I bought a farm/estate... and I must go see it"). This uses the Latin villam as a reference, meaning a private country estate. b) The Prodigal Son: In the famous biblical parable, the master "santa inan in sin thorf, thaz her fuotriti suuin" ("sent him to his farm/estate to feed pigs"). Here, the thorf is clearly a specific agricultural property owned by an individual. 2. The Village or Rural Settlement (Siedlung) This is where the word starts to describe a collection of houses, often defined by what it isn't (i.e., it isn't a fortified city). a) The Unwalled Town: The text defines dorf as a "vicus"—a place that has streets but "sine muris" ("without walls"). b) The Contrast with Cities: One example says, "manige uuesen in demo dorf, unmanige in dero burg" ("many people are in the village, but few are in the [fortified] city"). This shows dorf becoming a category of settlement size. c) Specific Locations: The text mentions "thaz thorf thaz dar giquetan ist Gethsemani" ("the village that is called Gethsemane"). 3. The Neighborhood or Quarter (Stadtviertel) This is a more niche use where thorf describes sections of a larger urban area, often in the plural (thorphun). a) Public Display: A warning against hypocrisy: "so thie lihhazara tuont in dingun inti in thorphun" ("as the hypocrites do in the assemblies and in the [streets/neighborhoods]"). Here, it translates the Late Latin vicos, meaning the public blocks or quarters of a town where people gather. 4. The "Crowd" or "Peasantry" (Menge von Bauern) This is the most "abstract" evolution. The word for the place starts being used to describe the type of people found there. a) The Rustic Multitude: One entry notes a scribe used dorf to translate rusticam manum ("a rustic hand" or "a crowd of country-folk"). b) The "Village-Dweller": The text even mentions a derivative: uillanus dorphere (literally a "villager" or "peasant"), showing how the word was used to build new social categories. Old High German retained the direction of this change in various ways. There is no doubt about that. The Gothic Bible uses the word haims to translate the Greek kōmē (village). Place names ending in -heim (in Germany) and -ham (in England) appeared frequently during the Migration Period (5th-6th centuries). There are also runic inscriptions that make more sense if the root is interpreted as meaning village or community. At least the shift looks more ancient. The codex Abrogans is a glossary, for example it is simply written the equivalence between 'uilla' (villa) and 'thorf'.

-

Again, as I said, in Codex Abrogans the meaning leans more towards a farmstead for Old High German. It is only later that the semantic shift happens for this branch. Your example with 'villain' is not correct. 'Villanus' doesn't mean 'villager' nor is equivalent for 'villager'. A villanus is a peasant or a worker in a farm estate, a villa rustica in the Roman perception. 'Village' is a semantic shift appearing much later during the medieval period and once again in the same direction: from a single farmstead to a collection of farmsteads. Villanus means 'villager' only in Middle English after a borrowing from French, where the semantic shift already happened. I don't see anything convincing for the moment to change my opinion.

-

Euler and Maurer are certainly respected, but they represent the 'divergence' school of the mid-20th century. Modern computational phylogenetics (like the Ringe work I cited) suggests a much tighter 'Germanic Core' than Maurer’s 1940s theories allowed for. Regarding the 'Elephant in the Room': Gothic is likely conservative because of the direction of semantic change. It is a documented linguistic trend for words describing land or enclosures to expand into words for settlements (think of English 'Town' from *tuną 'fence/enclosure'). It is almost unheard of for a word meaning 'village' to suddenly be downgraded to mean 'dirt field' in a single branch. As for why dictionaries list it as 'village': Dictionaries are tools of commonality. Since the West and North Germanic branches (which cover 90% of our surviving texts) use 'village,' dictionaries list that for the sake of the user. But if you look at the etymological root *treb-, the meaning is clearly 'to build' or 'a dwelling.' A village is a collection of dwellings; a farmstead is a single dwelling. Gothic, being the earliest snapshot we have, simply catches the word before the 'collection' phase took over the West Germanic dialects.

-

I don't see it that way. It is mainly Old Saxon and Old Norse from the 8th century that show this semantic shift, while Old High German shows an interpretation closer to that of Gothic. And languages do not always diverge abruptly; Germanic languages continued to interact for a very long time, and certain semantic shifts can become popular in one language or another depending on the context of the time. And your claim that Gothic was already unintelligible to West and North Germanic languages is BS. I can suggest you the following readings: Hans Frede Nielsen: The Germanic Languages: Origins and Early Dialectal Interrelations (1989). He explicitly argues against early, sharp divisions. Don Ringe: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2006). He supports a rather slow and gradual divergence and considers Gothic to be very close to Proto-Germanic as it has been reconstructed. This is the "gold standard" for the timeline of Germanic divergence. The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics: Specifically chapters on "Proto-Germanic" and "Early Runic," which describe the 1st–3rd centuries as a period of relative linguistic unity.

-

Beware that a reconstruction doesn't really determinate its meaning. The meaning is generally deduced from the descending languages inheriting the root. A reconstruction generally means we have no evidence for this word in Proto-Germanic, we are relying on later evidence from descending languages. The Gothic language is well documented from the 4th century AD onwards. That's the earliest Germanic language with significant information. Most of the other Germanic languages are really documented from the 8th century AD only. The usage and meaning of certain words can have changed significantly between two Germanic languages simply because of the time that has passed. For example the word *þurpą became þaurp in Gothic, which means farmland or farmstead, since it is used in the Gothic bible to translate the word agrós. In Old High German, the word became thorpf and it seems it is used in the Codex Abrogans (8th century AD) to translate the Latin villa, not in a large village meaning but more as a farmstead. But in Old Saxon, it seems the word changed its meaning and became used to designate a hamlet or a village.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Initial AppImages available for testing

Genava55 replied to hyperion's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

Anyone tried? It should be tested before releasing. -

Haimaz, Wihsa, Burgz Haimaz for home, hamlet, village. Wihsa for village or settlement in general. Burgz for town, stronghold.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Genava55 replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

That's why initially I proposed a tutorial on Alexander the Great's youth. Aristotle was his primary tutor from the age of 13. In 340 BC, the 16 years old Alexander was regent of the kingdom when his father laid siege to Perinthus and Byzantium. He fought and defeated the Maedi revolt, a Thracian tribe. He colonized their territory and founded a city which he named Alexandropolis. In 338 BC, he participated decisively at the battle of Chaeronea against the Thebans. He is clearly the best historical figure for a tutorial that builds to a crescendo and precedes an epic campaign. Edit, short introductions about the story: Edit: past messages -

Here the opinion of Nescio:

-

I think it is because @Nesciowanted to remove the feature, arguing that siege equipments cannot be used without the engineers/experts necessary.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

==[TASK THREAD]== Wonders of the World

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I put it there to not open a new thread for it. If it is an interesting task, open up a new thread. -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

==[TASK THREAD]== Wonders of the World

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

Ara Pacis or Altar of Peace The Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) is a renowned monument in Rome, commissioned by the Senate in 13 BC and dedicated in 9 BC to honor Emperor Augustus’s return from Spain and Gaul. Located in the Campus Martius, it represents the "Pax Romana" through marble reliefs featuring imperial processions, mythological figures, and fertility scenes, symbolizing peace and prosperity. -

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

A documentary on the Angles during the Roman Iron Age (1 - 375) and Migration period (375 - 568). A disclaimer: this video comes from the conservative sphere. This is a video that is fairly factual about archaeology and history. However, sharing the video here does not mean that we endorse all of the messages on this YouTube channel. Keep an open but critical mind. -

I think yes it would be better. You can make a ditch around the kurgan with a small pallisade and there add an entrance, with the statues.

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Civ: Germans (Cimbri, Suebians, Goths)

Genava55 replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Delenda Est

The earliest evidence for runes is the Meldorf brooch, dated around 50 AD. So no runes for the Cimbri. Petroglyph production declined sharply after 600 BC and it is really difficult to date a petroglyph. Furthermore, there is not a large quantity of petroglyphs in Denmark. Those were mostly found in Sweden and Norway. I would avoid petroglyphs for the Cimbri. It looks a lot like a boat burial, when a person is buried with a boat. Which is not attested for this period. The sinking of the Hjortspring boat is more probably a votive deposit, an offering to deities, from a war booty or a trophy. Furthermore, you choose a very small boat and you emphasize much more on the stone circle. Which is a bit problematic because the boat is probably the most important part. -

Vidéo+de+Evgueni+Kraї(2).mp4 I think you have enough variation

-

I think the transmission of metrics is disabled by default on installation.

-

Arsacids / Parthians Bactrian camels: Certainly Yes (Logistics) Dromedary: Certainly Yes (Logistics) Greco-Bactrians Bactrian camels: Certainly Yes (Logistics) Dromedary: Certainly No Tocharians and Yuezhi Bactrian camels: Certainly Yes (Logistics) Dromedary: Certainly No Bedouins Dromedary: Certainly Yes (Logistics & Combat) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Himyar Dromedary: Certainly Yes (Logistics & Combat) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Axum Dromedary: Certainly Yes (Logistics) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Macrobia Dromedary: Probably Yes (Logistics) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Garamantes Dromedary: Certainly Yes (Logistics & Combat) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Gaetuli / Libyans Dromedary: Probably Yes (Logistics & Combat) Bactrian camels: Certainly No Numidians Dromedary: Certainly No Bactrian camels: Certainly No Mandé–Soninke and Sao Dromedary: Certainly No Bactrian camels: Certainly No

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

The Kingdom of Kush: A proper introduction [Illustrated]

Genava55 replied to Sundiata's topic in Official tasks

...- 1.042 replies

-

- civ profile

- history

- (and 5 more)