-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Free Games and Offers

Lion.Kanzen replied to Widukind's topic in Introductions & Off-Topic Discussion

I had no idea, I love playing Clash Royale. The others I do not install due to lack of space on my cell phone -

Indeed it must be the other way around, that in real life rarely happened. At least under normal conditions, the cavalry served to end these pests.

-

especially IV. It has several thousand palisades and berry bush similar to the old model. Your Mongols could be similar to that of Empires Apart or our Xiongnu. We had the idea of using our cavalry to hunt. The scale of our game is better. sacrificing immersion in a history RTS game is a mistake.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Mercenary use in the punic and successor factions

Lion.Kanzen replied to PyrrhicVictoryGuy's topic in Gameplay Discussion

sorry but Carthage have swordman as mercenary, I don't see useless, at least that unit. -

Eso sería una segunda versión. Por ahora la v1 tiene el espíritu de ser sencilla. I also have a nomad shipwreck map planned similar to what it happened to Christopher Columbus in 1492 and the Santa Maria shipwreck. You shipwreck on a huge island and create a fort camp out of the remains. The island is full of natives with Stone age technology. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Navidad I like the idea of creating a palisade fort with the wood of the wreckage of a ship.

-

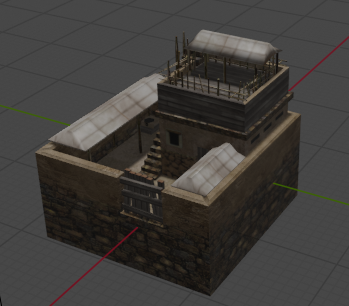

For now my plan is to bring generic material that serves multiple purposes to the game. the first one I will bring will be the Civic center or Villager center of a poor province. is poor and generic, so that it can be tested by any 0 A.D player on their maps,

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Nerfed archer accuracy XML file

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

Melee cavalry. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Nerfed archer accuracy XML file

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

I'd give them a good attack and a poor hp, Good archer defense (pierce) but fatal crush and hack armor. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Nerfed archer accuracy XML file

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

the idea is that , they are like mosquitoes, a pleasant pest to kill. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Tutorial Campaign

Lion.Kanzen replied to Freagarach's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

Some Gaia stuff, some wild animals to kill, maybe a wolf. A shipwreck. That's sounds cool. -

Ideally, they should be annoying, not efficient.

-

Maybe formation is necessary bonus.

-

I am not asking for hard counters, only looking for a logical way to stop the Mauryas. How should the Greeks work with their hoplites and pikemen? Maybe the mechanics should be a mix of spear and projectile (javelins) ------- Siege towers should be stopped with cavalry and slingers or with catapults(ballista).

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Addition of Han Chinese to 0AD

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

@Lopess could be used for Mesoamerican mods. It's just changing tones. -

Yes I agree.

-

@wowgetoffyourcellphone In your game they are quite balanced, the counters. I don't remember how the elephants worked, what were the units that counter them?

-

4+ vs an 1 it should be the formula. May be 8 hoplites.

-

did you do tests?

-

Skirmishers must take down Elephants and may be bonus for Bolt shooter vs Organic Units. in compensation for slow firing and to diminish the effectiveness of accuracy (in case of not being enough) or simply the bonus would be vs infantry and elephants.

-

I think the agreement was for all factions to have siege rams.

-

Bonus hoplite vs elephants?

-

on some maps, small mines should be increased.