Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 2026-01-21 in all areas

-

The more i think about it, the more I think we could just remove auto-attacking building all together. Like units do for Gaia buildings basically : don't do anything unless specified. Maybe since some cite the case where you could want units to start attacking/capturing everything nearby, violent stance would restore this poking holes in all nearby building with your spear for 40 min behavior.3 points

-

I am developing an AI called stevenlauBot. I have only made the game start move. All units go to the tree nearest to CC, cav goes to chicken, either by walking or teleportation, whichever faster. It looks cool! My plan is to make the AI to play standard tactics like how I usually play (only Han). It will be useful to practice 1v1.2 points

-

As Attack move also makes units to attack/capture buildings when they see it and Attack move(units only) attacks only units so the units doesnt get stuck attacking unnecesary buildings.2 points

-

Hey, I put this list together. It has every class, both the VisibleClasses and the Classes, for triggers, auras, techs, etc. Hopefully someone finds this helpful! classes.txt2 points

-

This problem should be no more in R28. They will only continue attacking buildings if you explicitly told them to attack or if there is no other unit available to attack.1 point

-

1) Yes. in Options > Networking / Lobby > There is an option "Max lag for observers". you need to set it to -1 (minus 1) so the spectators doesnt affect the game 2) IMHO. Yes and no. I believe It's more about ISP routing problems rather than distances. For example I mostly have some ping( ~300 ms) with some ppl from Asia, mostly from India but it's not everyone from India, just some ppl. And these same players with some lag with me doesnt lag with others in the same continent ( south america ) And I agree with this too.1 point

-

1) there is an option for the host. either the spectators don't influence the game, or the game needs to wait for the spectators. Most hosts use the first option. If there is the other option, any spectator can cause a lot of lag for the game. 2) I believe it does. huge distances will result in a bigger delay for exchange of data, so there will be extra network lag. By the way, network lag isn't the same as performance lag. For example, a 1vs1 between a strong European computer and a strong Australian computer can still be much less "laggy" than a 1vs1 between two very slow European computers.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

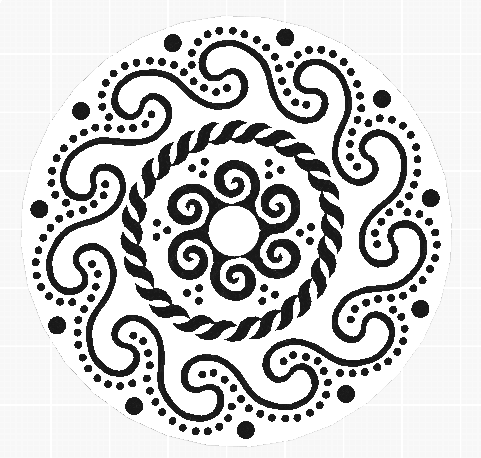

suggestions and more ideas are welcome taking into account that there may be more factions from the iberian peninsula (spain and portugal in the future).1 point

-

1 point

-

it would be nice to have a vector graphics editing program handy like inkscape. https://inkscape.org/1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I'm going to need time first to vectorize the symbol then to recreate( draw) from the reference.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

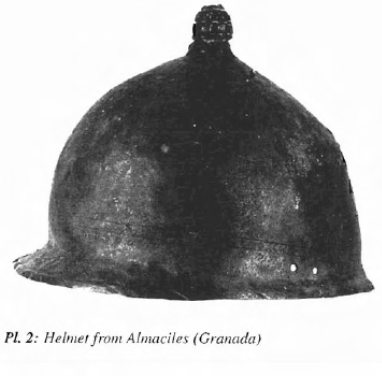

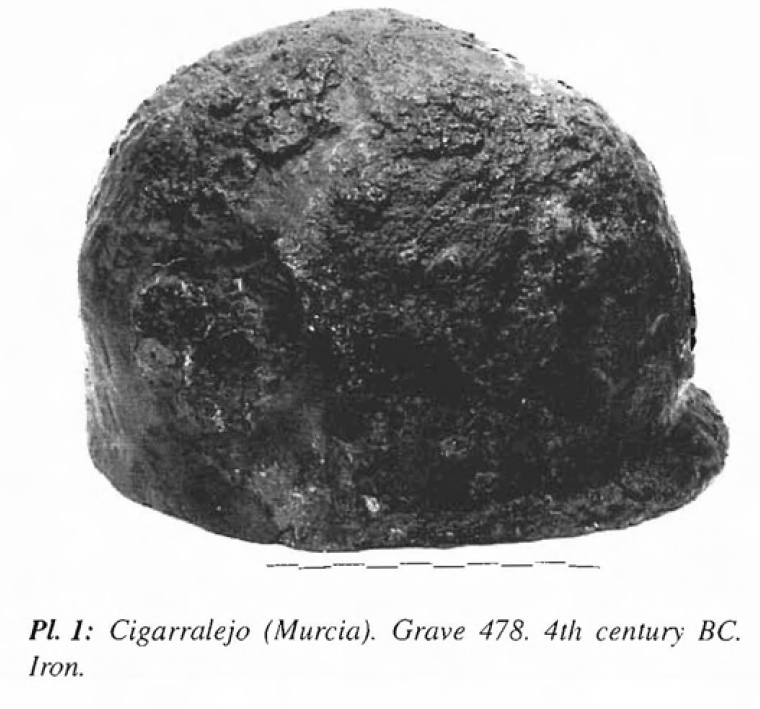

That's not bad but I think there is a misunderstanding I want to clarify. The typology of Montefortino helmets is a mess. Everybody call Montefortino a family of helmets that have very different features, conceptions and technology. This is due to a 19th legacy from early historians and it has spread everywhere. First of all, a helmet in bronze is always different from a helmet in iron. This is simply not the same technology and the same conception. They could cast bronze, because bronze can be easily molten. Not iron, at that time the only way to make an iron helmet is to forge it, hammering iron sheets and giving it the desired shape through a long processing. Finally, the Montefortino are made by various people. Romans, Etruscans, Celts, Phoenicians, Iberians and even Greeks at some point. It has a very long history and it has seen specific cultural development. The biggest difference is between the Celtic iron version and the Mediterranean version in bronze. Here's a link about the Roman Montefortino with several variants: https://www.res-bellica.com/en/montefortino-type-helmets-a-chronology/ You should notice that the bottom and the neck guard are all straight: While a Celtic Montefortino in iron is like this: As you should see now, this is really two different helmets. The iron helmet made by the Celts has a neck guard going down, because it is a separated piece riveted to the bell. While in the bronze helmet made by the Romans, the neck guard and the bell are made of a single piece. Those examples are simply to show you the most different features. Some Celtic helmets in iron don't have neck guard going down like this. There is even some Celtic Montefortino made in bronze. Those examples are simply the extreme cases to help you picture it. But generally bronze Montefortino have this straight line. It has changed only at the very end of the Republican period (1st c. BC) when the Buggenum variant started to appear: So back to the Iberian bronze Montefortino, it has clearly the same straight line feature: The case of the iron helmet from Cigarralejo is bothering. Quesada-Sanz calls it a Celtic type, and it has been found in a purely Iberian context in south-east Spain: However, I think this is a case of unintelligence due to the horrible mess constituting the Montefortino typology. This is not a Montefortino. Quesada-Sanz is mistaken and the only one having a clear mind on this one is Garcia-Jimenez. He has questioned the classification of this helmet as Montefortino and see similarity with the older Bockweiler type that has been found in Hallstatt. Cigarralejo has no tip, it has a straight line at the bottom and it is made in iron. There is not a single comparable evidence from a Montefortino helmet. If it is a Celtic type, then the tip is missing. Which is possible because Garcia-Jimenez mentioned that the helmet has been poorly restored.1 point

-

Lusitania – HIST. 1. Lusitania was the name given, generally, to the territory situated in the occidental end of the Iberian Peninsula, and which started in the North after the Durius (according to Pliny) and with “its flank to the North and his front to the Atlantic ocean”, in the brief description by Pomponius Mela. The name “Lusitania” arose from Lusus (the root Lus was quite common in Celtic territories, as A. Schulten pointed out). Thus, the country name derived from the onomastic vocable Lusus, just like all consanguinity and tribe names – mainly the tribe leader – derived from this proper name: Lusitania means “tribe” or “people of Lusus”. However, Lusus does not appear in any ancient text, despite the multiplicity of other names with the same Celtic root: Lusa, Lusatia, Luseous, Lusoius, Luseu, etc, or even Lusones in the indication of Leite de Vasconcellos, who considers Lus as a theoretical common root to Lusus, Lusones and Lusitania. The imposing certainty is this: names with the root Lus are common in Celtic countries; the Lusitanians – people of autochthonous root in this peninsular nook – formed, through crossing marriages, a group of tribes with the Celts, with Celt-Iberian characteristics and language, after the Celtic and Iberian invasions, in the beginning of the Iron Age. This explains the frequency of Celtic names in the ancient Lusitania. Every text which refers to Lusitania, its name, territory limits, geographic, historic and ethnographic aspects are from Greek and Roman classic authors and also from some writers born in Iberia, as the already quoted P. Mela. After the wars between Carthage and Rome and the ones with Viriato and his successors, the Romans kept the name “Lusitania” in the administrative division they imposed in the Iberian Peninsula. 2. The geography of Lusitania originated a series of problems as to the exact limits of the territory. Strabo considered three well-determined regions in the West of the Iberian Peninsula: the Cineticum (Algarve), the Mesopotamia (area between the rivers Tagus and Guadiana), and the Lusitania itself or primitive Lusitania, between the Tagus and the extreme North of Galicia (Cantabria), thus occupying two wide areas, the Callaecia (Galicia) and the district between the rivers Tagus and Douro. Lusitania was split in two distinct zones: the southern one, soon dedicated to trading profits and contacts with the Mediterranean and the civilization; and the central and northern zone, the former rough and plain, the latter of a wrinkled orography, tortured by deep geologic eruptions, hard, mountainous and wild. As to limits, at the time of the castrum culture, the country was apparently situated between the river Guadiana, in the South, and the rivers Douro or Minho in the North. The Lusitanian homeland occupied the northern half, the mountainous region between Tagus and Douro (the current “Beiras”). Physically, the occidental area of Iberia not only shows a diversified physiognomy from North to South – divided by the valley of Tagus – but was also a rich area, as its rivers were praised because of their auriferous sands by classic writers like Strabo, Catullus, Ovid, Lucan, Silius Italicus, Juvenal, and others. Rivers were also important communication ways: Durius, Limia, Vacua, and Munda. Tagus, in the 1st century, was 20 stadiums wide (approx. 3700 meters) in its mouth. The river Minho could be sailed up to 800 stadiums. The southern region is plainer, and we can highlight the zones of Mesopotamia and Cineticum, the latter separated from the rest of the territory by two mountain ridges which establish the cut between the current Alentejo and the farthest meridional part of the country – mountains which are currently called Monchique and Loulé. The most important river was Anas, full of fish, which was the limit between Cineticum and Ager Tartessius. The Lusitania was a wide territory, which reaches the width of 3000 stadiums in the 1st century, as a country of many contrasts: promontories, bays, coves, wide beaches, rivers rich in fish. Strabo sincerely praised the fauna in every book he wrote about the Peninsula. The fauna was portentous in Lusitania: magnificent horses (similar to the Parthian ones), wild boars, harts, wolves, foxes, jennets, lynxes, goats, hares, rabbits, this latter so abundant that it brought grave consequences to Turdetania, destroying tree and bush roots. This is why the people called Hispania – that is Land of the Rabbit – to ancient Iberia. The Lusitanian west coast is described by authors like Strabo and Avienus, mentioning the indented littoral, rivers of wide and deep estuaries, protected coves and capes like Barbarion (currently “Espichel”), the Promunturium olissiponense, the Mondego cape, the Promunturium Sacrum and the Avarum. The territory was rich in ore: gold, copper, tin, silver and iron. In addition, there was the natural richness of equine, caprine, bovine and swine livestock; the medicinal waters which were the basis of the rude Lusitanian medicine. Quoting Polybius: “The well-tempered weather, the prolific animals and people and the fruits which never spoil the country.” The Romans, who established the administrative board of Iberia under Augustus orders, insert Lusitania in the Hispaniae Ulterior province. During the overcast times of the Low Empire, its name was not modified: Lusitania. 3. The map of the distribution of people and tribes in the Lusitanian territory in the proto-historic epoch shows a stirring and colorful miscellany. The Conii or Cinets, who had contacts with the North – that is, with the Lusitanians themselves – lived in the Cineticum region and used a language with Greco-Punic-Tirsenic influences. The Vetons, who were related to the Lusitanians and were their allies, lived in the occidental Lusitania; the Turduli Veteres lived near the river Munda and in the country of Vacua. This tribe probably built the cities Eburobritium, Collipo, Aeminium, Conimbriga and Talabriga. The Transcudans and the Igaeditans lived between the Tagus and the Douro (After, the Roman city Egitania; now Idanha-a-Velha). Pliny also refers the Paesuri in the Douro’s south. Furthermore, an inscription in the bridge of Alcântara refers the Interamnenses, Talori, Arnui and Colerui tribes. The Celts, who probably found the cities of Lacobriga, Mirobriga, Anobriga, Arandis or Arani and Baesuris, lived in the Mesopotamia between the Tagus and the Guadiana. The Callaeci or Calaics and other celtici like Grovii lived from the river Douro to the North, beyond of the Lusitanian border (end of Galicia). There were also the Bracarii – ethnic groupings who lived in the mountains – the Leuni and the Seurbi. The Turodi lived in the wild region which is now the region of Trás-os-Montes. We presented here just a few tribes among the ethnic variety of Lusitania, showing the weak social unity of the country. 4. The Lusitanians were the most important people, welded by abundant contacts and crossings with other tribes – invaders, most of the times. Concerning the archeological richness of Lusitania before the Iron Age, we can affirm that the history of Lusitania gains its originality with the Lusitanian people, although they had constantly been in contact with superior people and cultures of Mediterranean provenience: the Phoenicians of Tyro, who shored in the Mediterranean and Atlantic littoral of the Peninsula in the 12th century BC, sending their vessels to the mysterious reign of the Tartessians (South of Hispania); the Carthaginians, who occupied the area up to the North of the Tagus; the Greeks from Phocaea, with their characteristic littoral occupation or in the mouth of big rivers, in the way of the tinful areas of the northern Peninsula; the Romans, who intervene in economic businesses in the Peninsula after the wars with Carthage. During the 2nd Punic War, initiated in 219 BC, the Romans begin their fight to conquer Iberia and destroy Carthage. After a long period of fights, revolts, troop and population movements, the Lusitanians prepared their spectacular offensive. They advanced to the region of Betis, allied with the Vetons and other tribes. The Lusitanian war starts in 155 and the Viriatian war lasts from 147 to 138 BC. The Iberian Peninsula, which was a conquest desire for other civilizations since the early antiquity, suffered the harshest reverse of its agitated history: since 193 BC, the tribes of the Peninsula decide to initiate the war against the Romans in Betis. The Lusitanians, after the shameful treason of Galba (when 9000 Lusitanians were barbarously slaughtered and 20,000 were sold in Gaul as slaves), organized themselves around Viriato, and the following years were the hardest times for the Roman hosts: Galba, Lucullus, Vetilius, C. Plaucius, Fabius, Servilianus, Scipio, were defeated by the brave Lusitanian leader. The Lusitanians were the only Iberian tribe who maintained their freedom war for such a long time, with the peculiar characteristics we know. We call Lusitanians to the Iron Age group of tribes. They dedicated to hunting, a rudimentary agriculture (mainly the mountain tribes), shepherding, and fishing, but they also had an important economic life – which is proved by the existence of commercial cities like Moron – a rich agriculture in the low areas, an intense life of relation, an art, a bellicose and liturgical literature; they lived in walled cities on high cliffs for defensive reasons which are called castros or crastos, citanias or cividades (examples in Portugal: citania of Briteiros, Sanfins, Sabroso, Cividade of Terroso; castros of Santa Luzia, Castelo dos Mouros in Idanha-a-Velha, Monsanto da Beira, etc.). The houses were round, made of stone, covered with stems, some of them without windows and some of them rectangular. The circular houses sometimes reached a diameter of 5 meters (in the Citania of Briteiros). Walls reached 50 centimeters thick. The walls of big castros were polygonal or cyclopic – their circuit sometimes lengthened 50 meters to 1000 meters and was sometimes reinforced by a second defensive curtain. 5. Comforts did not miss daily life: clothing, manufacturing of flax and wool clothes, leather, esparto, metal and ceramic (doria) objects, artisans, blacksmiths, millers, warriors, farmers, priests, housewives taking care of their children, toasting acorns and milling them to make bread, grinding corn with manual millstones, and a typically Iron Age loom in each familiar aggregate. They had varied food and multiplicity in living styles. Lusitanians lived according at least three living styles: mountain life, plains life, and littoral life; these two more dedicated to trading between near settlements and external trading with the Mediterranean, Northern Galicia regions, Betica and Turdetania. They exchanged products directly and with pieces of gold or silver, like money. Even coins were used in some southern cities, like Baesuris, Ebora, Ossonoba, Sirpens, Myrtilis and Salacia. 6. The Lusitanian religion was polytheist. They believed in natural forces: they practiced physiolatry and magic impregnated by extraordinary beliefs, which are described by Strabo, Pomponius Mela, Pliny, Avienus, Diodorus and others. They worshiped the rivers: Tagus, Mondego, Lima (Limia, Flumen oblivionis that is, River of Oblivion), the woods, the big promontories, the Moon, the stars and the winds (the Serra of Sintra was the altar of the Moon cult; according to Martian of Heraclea and Ptolemy, it was called the Serra of the Moon). They also had the main gods: Endovelico, Ataegina, Macario, Revalanganiteco, Ilurbeda and Trebaruna. The Lusitanian pantheon is full of earth and fertility gods. The woman and the earth were united in the cult of the holy fecundity, as in any primitive tribe. Warlike tribes worshiped the god of war and the gods of metallurgy were also worshiped in the whole territory. They practiced human sacrificing, but only with prisoners and war enemies. The dead were cremated, and their ashes were buried in little clay urns: cremation, dancing and singing, and a funereal banquet in the end. 7. The auriferous richness of Lusitania originated the castro jewelry (*): brooches, bangles (**), pins, torques, bracelets, ear-rings and other rings, which were found in the castros of Lanhoso, Lebução, Paradela do Rio (Montalegre), Estremoz, Briteiros, and many other localities. Techniques: cold hammering and lamination, and the foundry; ornamentation techniques: the granulated, grained, or powdered, and ornamentation of pricks cut with chisel, with globules (spouting), as in the famous bracelet of Chaves. The following tools were found in excavations: hammers, anvils and chisels. The rude Lusitanian structures were modified with the Roman occupation. The Lusitanian-Roman epoch is a period of big agitation in social, economic and military life: mass migration of population who colonized regions outside the primitive Lusitania – like Valencia – and outside the Peninsula – like Romania; destruction of castros and annexed pathways; creation of roads, new urban centers over the remains of old settlements, monuments who attest the existence of a superior civilization. But what is remarkable is the predominant permanence of the Lusitanian facies in the Roman civilization of the Lusitania, although the history of the autonomous Lusitania ends in 45 BC. It becomes a Roman province in 25 BC, with precise borders in the river Douro, northward, and the Mediterranean, southward, with a wider territory than the one of Viriato’s epoch, and constituting an “imperatorial province”. With Claudius it was subdivided in Conventus: the Pacensis (seat in Pax Julia), the Scallabitanus (seat in Scallabis), and the Emeritensis (seat in Emerita Augusta). In Lusitania, Romans erect their essentially practical architectonical art, with monuments of big size, some of them beautiful and lasting: bridges, aqueducts, temples, construction of magnificent houses with marble, statuary, and inimitable mosaics – influenced by Roman and Greek artists who set foot on the Lusitanian land – which can be seen in many cities like Conimbriga, Vila Cardilio (municipality of Torres Novas), Torre de Palma, Pisões (municipality of Beja), Abicada (municipality of Portimão), Estoi (municipality of Faro), and greatly important cities like Olisipo [Lisbon], which was restructured, Egitania Emerida Augusta, Conimbriga, Pax Julia, etc. Concerning ceramic, we can notice that little plain or ornamented vessels and dolia in the Lusitanian castros. In the former, there is ornamentation in S’s, chess-pattern, and triangles, and also ceramic with stamped matrixes (rosettes, stylized palmipedes, etc.). Later, this ceramic was replaced by the magnificent arretine ceramic or with varied ornamentation of Gaulish or Italic importation. Not much later, Lusitanian potters managed to improve the manufacturing of terra sigillata, which was called Hispanic by convention. In jewelry, other examples of several origins cause modifications in the castro jewels. The Romans oppose their fine and perfect statuary – which can be seen in several museums – to the bellowers and rude statues of Calaic and Lusitanian warriors. In small-sized statuary, the quantity of ex votos and little worship figures exemplify the variety of Lusitanian cults and the perfect Roman assimilation of the polytheist religion of the Lusitania of castros (*). 8. Roman Lusitania – Lusitania was one of the territories which resulted from the administrative division of the old province of Hispania Ulterior, made by Augustus. Before this division Hispania was constituted by two big provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, consequence of the Roman conquering effort, each one ruled by a praetor since the beginnings of the 2nd century BC. In this first administrative organization of Hispania, it is not easy to distinguish the military purposes from the mere administrative ones. Anyway, this first administrative division modeled the future initiatives of organizing the territory; in fact, the old republican administrative divisions are the basis of Augustus’ new territorial board. It is also necessary to understand that Hispania was homogeneous neither in physic geography nor in human geography, and the living style of the different tribes who habited there were very different; the urban civilizations of the Mediterranean littoral were culturally very distant from the semi-nomad people of the mountains, mainly dedicated to shepherding. When Augustus reorganized Hispania he was certainly thinking about practical economic situations, which would allow the Roman dominance in the territory, and not in the interests of the several tribes who lived there. The division of the Hispania Ulterior in two provinces, Betica and Lusitania, corresponded to a alleged military necessity – the territories where the presence of military effectives was necessary for the complete control of the region belonged to the Emperor; the Senate was responsible for the administration of the southern territories, which were conquered by senatorial initiative, and where the eldest Roman urban nucleuses were installed and flourished, being the presence of the armies already unnecessary. The borders of the Roman province were the Atlantic Ocean, as West and South limits, the course of the river Douro, as the North limit, and eastwardly the course of the river Guadiana – which washed the capital city, Emerita Augusta (the current Spanish city of Mérida) – by the Spanish table-land up to the interior course of the Douro, and then down to the sea. The borders of this Roman province were kept until the Low Empire, and not even the administrative reform of Diocletian, in the end of the 3rd century, inflicted significant changes in both Lusitania and Betica. Authors are not unanimous either about the exact borders of Lusitania or the date when Augustus administratively remodeled the territory. Discrepancies are partially due to a confounding of the alleged “ethnic unity” – the Lusitanians – with the Roman administrative region, and due to the nationalist exploration that has been being ideologically implanted in the national [Portuguese] historiography since André de Resende. In the border controversy, the Portuguese territory in the left margin of the Guadiana has been attributed both to Lusitania and Betica, according to different opinions. As for the date when the province was created, it is known that it occurred somewhere between 27 BC (accepting the testimony of Dion Cassius), to 16 BC – 13 BC, when Augustus returned from his second journey to Hispania. *The Portuguese adjective used was castreja, which is an untranslatable word and means “belonging or referring to the epoch of castros”. A castro was, as said earlier, a fortified Lusitanian settlement. (Translator’s Note) **The Portuguese word is víria, which means “bangle used by ancient warriors”. Hence the name Viriato, which meant “warrior who used a víria”. I do not know the English translation of this word. (Translator’s Note)1 point

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

.thumb.jpg.c3fb1e93f55dd587d8281ef58d932508.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)