-

Posts

2.300 -

Joined

-

Days Won

23

Everything posted by Nescio

-

To clarify, I'm not totally against it. While the situation described in the Arthaśāstra postdates the Mauryas, at least some of the weapons listed in 2.18 would have existed in the 1st C BC. Well, we know onagers were invented by the Romans during the 4th C AD, therefore the Indian weapon wouldn't have resembled one. The same reasoning applies to the mangonel (“traction trebuchet”) and springald designs. This also speaks against it: Sarvatobhadra is a cartwheel-shaped device that, when spun, hurls stones. Now I don't know what to make of that cart-wheel, might it have been horizontal? The easiest solution would probably be to give the Mauryas a Greek-style (i.e. Macedonian) torsion engine. I'm not saying they had, just that's not inconceivable.

-

That “catapult” would have been invented during the Magadha–Vajji War of 484–468 BC, i.e. around the time of Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC) and the Greco–Persian Wars. However, it's very important that the Buddhist and Jain literature emerged many centuries later. The source in question, the epic Trīṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacharitra “Lives of Sixty-Three Great Men”, was written by the Jain scholar Hemachandra (AD 1088–1173). It's not entirely impossible they just might have existed. We just lack sources, descriptions, dimensions, drawings, etc., which would probably make it quite challenging for artists to model and animate one, but if someone wants to give it a try, I won't stop you. That's not really surprising. Indians had neither bricks nor stone architecture at the time; war elephants and fire are very effective against wooden structures. The first attestations of battering rams I know of are from the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), and those emerged in a region where wood was scarce and bricks and stone architecture existed for millennia.

-

Yes, the Arthaśāstra is a fascinating text. The relevant section is book 2, chapter 18, especially 2.18.5 and 2.15.6. It's mostly a list of names, though, most of them poorly understood. There are suggestions from commentaries and scholars what they could mean; they're speculative, though. More importantly, there are no drawings, descriptions, measures, weights, distances, etc., making it very hard to do anything with it. Apparently we had the same idea. Possibly. We know that during Hellenistic times a plethora of complex engines existed (see e.g. Philo of Byzantium's treatises) which otherwise disappeared without a trace. By the time the Romans (Caesar's legions in the 1st C BC) started making their own torsion engines, as opposed to relying on Greek allies to provide artillery or using what they seized from the arsenals of Syracusae, Carthago Nova, and other cities they conquered, there was basically only one (though highly effective) torsion engine design left.

-

First of all, I apologize for reviving this old thread. I did so because I believe it's still relevant, possibly even more than in the past, now siege workshops have been enabled for all civilizations and war elephants and battering rams become increasingly different. The traditional view that Chanakya (the mentor of Chandragupta Maurya) was the author of the Arthaśāstra is no longer held. In fact, the consensus is that not only the text itself, but also its sources postdate the Mauryas. For more information, see this post: https://wildfiregames.com/forum/index.php?/topic/27113-bibliography-and-references-about-ancient-times/&tab=comments#comment-402302 Did they? Do you have any reliable sources? As far as I know there is no evidence the Mauryas had artillery. That said, it's not entirely impossible either: the Mauryas emerged in the power vacuum left by Alexander's campaigning in India. Alexander's army had skilled engineers and multiple Greek cities were founded in the Punjab (now Pakistan), which became part of the Maurya empire (and outlasted it), therefore it's theoretically conceivable (though quite speculative) they supplied the Mauryas with Greek torsion engines and crews.

-

Bibliography and references about ancient times (+ book reviews)

Nescio replied to Genava55's topic in General Discussion

A text frequently mentioned in connection with ancient India in general, and the Mauryas specifically, is Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra. You can find the Sanskrit at: https://sarit.indology.info/kautalyarthasastra.xml The text was considered lost for centuries, but rediscovered in 1905. The first complete (English) translation, by R. Shamasastry, appeared in 1915 (it's now in the public domain and available at Wikisource); however, this translation is often faulty at best: when the work reappeared, it was poorly understood; many of the words were unknown and did not appear in any Sanskrit dictionaries or commentaries available at the time. A second manuscript appeared later; both derive from a single version from Kerala. There's also fragmentary manuscript from Northern India, and four fragmentary commentaries have been found. Based on these R. P. Kangle published a critical edition in 1960 and a new English translation in 1963. The Arthaśāstra has been widely studied and the scholarly understanding now is much better than it was fifty or hundred years ago. A new, good, and recent translation is: Patrick Olivelle King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India : Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra : A New Annotated Translation (Oxford 2013) To properly understand the text, one should read the introduction carefully. It's over fifty pages, and contains a wealth of information. As you may know, the Mauryas (c. 323–184 BC) were the first Indian empire to rule most of the subcontinent. After three generations (Chandragupta, Bindusara, Ashoka), it shattered and a Mauryan rump state was ruled by a succession of kings for another fifty years. Centuries later a king Gupta founded the Gupta dynasty (late 3rd C AD – 543); his grandson greatly expanded the state and took the name Chandragupta I, after the founder of the Maurya dynasty; his son Samudragupta and grandson Chandragupta II further expanded it. The Guptas were only the second empire to control most of India; their heartland was in the same region as that of the Mauryas, and they had the same capital (Pataliputra). For this and other reasons, the Guptas strongly identified themselves with Mauryas. The Gupta period was a golden age of India, and many Sanskrit texts were canonized under them, including the most important, the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics. Traditionally Kauṭilya was equated with Cāṇakya and the name Viṣṇugupta as the author of the Arthaśāstra. This is no longer accepted in modern scholarship. Kauṭilya is the author of the work; his name is mentioned in the text itself, as well as in Manu and other texts; the other two are not named, they're added in the later tradition. Cāṇakya is the well-known teacher, advisor, and chancellor of Chandragupta Maurya; he's likely a historic person whose name and fame became legendary (not unlike Buddha, Socrates, and Jesus). Kauṭilya was most likely identified with Cāṇakya, for political and symbolic reasons, under Gupta emperor Chandragupta I. Viṣṇugupta is a highly symbolic name: Viṣṇu is the most important god and Gupta the name of the dynasty. It was probably added as a third name (three is very symbolic number) later under the Guptas, possibly under Chandragupta II. Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra has been dated as early as the Mauryas and as late as the Guptas. Modern scholarship has shown neither can be the case, both on linguistic grounds and content and culture. Kauṭilya compiled his work from several older works; we know this both because it lists several names, and because the work covers heterogenous topics and uses very different words in the first part(s) of the work than in the rest. It was probably titled Daṇḍanīti (the title Arthaśāstra was attached to it centuries later). An important scholar named Manu, from the Manusmṛiti (“Manu's Laws”, probably from the 2nd C AD), extensively used Kauṭilya's work. From it it's evident the version used was quite different from the one known in the present, therefore it must have been overhauled (at least once) afterwards, the so-called Śāstric Redaction. This restructured the text, divided it into chapters, added chapter-ending verses, enumerations, and a table of contents, and inserted new chapters, dialogues, and a heavy emphasis on number symbolism. Kauṭilya's sources were probably written between c. 50 BC and c. AD 50. Not later, since only silver and copper coins are mentioned; gold coins were introduced c. AD 100 but not mentioned in the text. And not much earlier either: The text explicitly forbids the use of wood in fortifications, whereas it's known from archaeological finds (and Greek texts) that the Mauryas had wooden city walls; stone fortifications and bricks were used in India only after the Mauryas. Moreover, the Mauryas ruled a vast empire and had a huge army; the world in the Arthaśāstra consists of many small kingdoms, confederacies, and tribal states (as was the case after the Mauryas). Furthermore, corral is mentioned multiple times (in books 2, 5, 7); it came from the Mediterranean; one of the types is called ālakandakam, from Alexandria in Egypt, another vaivarṇikam, possible named after the Greeks (Ionians); while India is known to have traded with the Persian Gulf already in the second millennium, direct sea trade between Egypt and India took off only after c. 100 BC. Kauṭilya's version was probably compiled somewhere between AD 50 and 125; the absence of gold coins favours the earlier date, and it can't have been much later, since the text was already well known by the time of Manu. The Śāstric Redaction probably happened between AD 175 and 300. Not earlier, because this version was not known to Manu, and not later, because this was the version known to and heavily influential at the Gupta court of Chandragupta I and his successors (AD 319 onwards). Basically Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra is not reflective of India under the Mauryas. Nevertheless, it's a fascinating and important text, worth reading. -

For the record, I did just rebuild 0 A.D. from scratch and did not encounter your error (Fedora 32 and gcc 10.2.1 here, not Artix Linux). Doing a grep shows: #include <deque> is present in the following files: Whether or not it should be include in any other files is something for people more skilled in C++ than me to investigate and decide. [EDIT] #include <queue> is present in:

-

Indeed, the debate is nothing new, it started already in the late 19th C, and it will probably continue until 2300-year-old elephant bones suitable for proper DNA analysis (both nuclear and mitochondrial) show up in Egypt on the one hand, and on the other in Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Spain, Sicily, or Italy. What's also fascinating is that the forest elephant hypothesis does not solve all issues, and various old suggestions resurface from time to time. Yes, I read that article too. Basically the author is saying that the notion that Indian elephants are bigger is a topos (a literary commonplace), which is not as far-fetched as it may sound to non-classicists; topoi are actually quite common. Moreover, Schneider 2016 is not the first to propose it (see Tarn 1926). Furthermore, assuming that Ptolemaic war elephants were forest elephants does not make Polybius unproblematic. First he writes 5.84.2–4: [2] ὀλίγα μὲν οὖν τινα τῶν παρὰ Πτολεμαίου συνήρεισε τοῖς ἐναντίοις· ἐφ᾽ ὧν ἐποίουν ἀγῶνα καλὸν οἱ πυργομαχοῦντες, ἐκ χειρὸς ταῖς σαρίσαις διαδορατιζόμενοι καὶ τύπτοντες ἀλλήλους, ἔτι δὲ καλλίω τὰ θηρία, βιαιομαχοῦντα καὶ συμπίπτοντα κατὰ πρόσωπον αὑτοῖς. [3] ἔστι γὰρ ἡ τῶν ζῴων μάχη τοιαύτη τις. συμπλέξαντα καὶ παρεμβαλόντα τοὺς ὀδόντας εἰς ἀλλήλους ὠθεῖ τῇ βίᾳ, διερειδόμενα περὶ τῆς χώρας, ἕως ἂν κατακρατῆσαν τῇ δυνάμει θάτερον παρώσῃ τὴν θατέρου προνομήν· [4] ὅταν δ᾽ ἅπαξ ἐγκλῖναν πλάγιον λάβῃ, τιτρώσκει τοῖς ὀδοῦσι, καθάπερ οἱ ταῦροι τοῖς κέρασι. Only some few of Ptolemy's elephants came to close quarters with the foe: seated on these the soldiers in the howdahs maintained a brilliant fight, lunging at and striking each other with crossed pikes. But the elephants themselves fought still more brilliantly, using all their strength in the encounter, and pushing against each other, forehead to forehead. The way in which elephants fight is this: they get their tusks entangled and jammed, and then push against one another with all their might, trying to make each other yield ground until one of them proving superior in strength has pushed aside the other's trunk; and when once he can get a side blow at his enemy, he pierces him with his tusks as a bull would with his horns. Which is followed by 5.84.5–6: [5] τὰ δὲ πλεῖστα τῶν τοῦ Πτολεμαίου θηρίων ἀπεδειλία τὴν μάχην, ὅπερ ἔθος ἐστὶ ποιεῖν τοῖς Λιβυκοῖς ἐλέφασι· [6] τὴν γὰρ ὀσμὴν καὶ φωνὴν οὐ μένουσιν, ἀλλὰ καὶ καταπεπληγμένοι τὸ μέγεθος καὶ τὴν δύναμιν, ὥς γ᾽ ἐμοὶ δοκεῖ, φεύγουσιν εὐθέως ἐξ ἀποστήματος τοὺς Ἰνδικοὺς ἐλέφαντας· ὃ καὶ τότε συνέβη γενέσθαι. Now, most of Ptolemy's animals, as is the way with Libyan elephants, were afraid to face the fight: for they cannot stand the smell or the trumpeting of the Indian elephants, but are frightened at their size and strength, I suppose, and run away from them at once without waiting to come near them. Note Polybius' cautious “I suppose” (ὥς γ᾽ ἐμοὶ δοκεῖ), though. If the Ptolemaic elephants were indeed forest elephants, then 5–6 makes sense: forest elephants are certainly smaller than Indian elephants. However, then 2–4 becomes problematic: Ptolemy's elephants were clearly large enough to carry turrets (!) and to match Antiochus' Indian elephants forehead to forehead (συμπίπτοντα κατὰ πρόσωπον αὑτοῖς). Gowers 1948, Gowers and Scullard 1950, and Scullard 1974 (yes, the two advocating war elephants were forest elephants) suggest that Ptolemy IV may have had not only forest elephants (which refused to fight and fled), but also some Indian elephants (which were the ones that did engage Antiochus' elephants). Charles 2007 argues this is not only a possibility, but actually the most likely explanation. Moreover, Ptolemy's (few) Indian elephants would have had turrets, but not his forest elephants (the majority). Charles concedes other scholars believe Ptolemy IV had no Indian elephants: Moreover, in his 2016 article, written in response to the 2014 Eritrean elephants genetic study, Charles gives the following possibilities: Ptolemy had only forest elephants, those that engaged the Indians were older, larger males. Ptolemy had mostly forest elephants (which were afraid), but also a few Indians (which did fight). Ptolemy had mostly forest elephants (which were afraid), but also a few bush elephants (which were much larger and fought). In this case the forest elephants would be those from Τρωγοδυτική in the Adoulis inscription and the bush elephants would be from Αἰθιοπία. Ptolemy had only bush elephants, but most were too young or too poorly trained and refused to fight. Unlike in 2007, he now dismisses scenario 2, stating that it's unlikely any Indian elephants of his predecessors would still be alive under Ptolemy IV. This leaves scenarios 1, 3, and 4. Scenario 1 could work, especially if “some of the Seleucid Indians were not fully grown, and were therefore a better match for adult forest elephants”. Scenario 3 is problematic, if the Ptolemies had access to both forest and bush elephants, why would they bother catching inferior forest elephants, when bush elephants would offer a very real military advantage over the Seleucids? Scenario 4 is supported by the recent DNA research, but is at odds with the notion that Indian elephants were bigger than African elephants in Antiquity, and if the Ptolemaic elephants were bigger, then it raises the question why they failed to defeat the Indians. In the end Charles favours scenario 1. (Unlike him, my order of preference is 4, 2, 1, 3. ) To end this post, I'd like to point out another article by Charles, written only two years later: Michael B. Charles “The Elephants of Aksum: In Search of the Bush Elephant in Late Antiquity” Journal of Late Antiquity 11.1 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1353/jla.2018.0000 In it he entertains the idea that the Aksumites may have had at least one bush elephant, the one that was shipped across the sea to attack Mecca, in what became afterwards known as the “Year of the Elephant” (it's date is disputed, somewhere between AD 550 and 570), and even got a surā in the Qurān named after it. However, that's beyond our timeframe. The reason I'm mentioning it is to illustrate that bush elephants as war elephant is gradually becoming an acceptable possibility, even among scholars who earlier accepted Gowers and Scullard's view of only forest elephants. That's it for today, I hope you like it.

-

What I wrote was: Yes, I know, and I actually pointed that out myself, in the other post: While the forest-savanna mosaic has a different shade of green than the equatorial forests of Congo, it also has a different shade of green from the Sudd and surroundings in South Sudan, as well as a different shade of green from that covering a significant part of Ethiopia. This is simply not true. Really a lot of DNA analysis has been done in the last two decades. I'll discuss this in a separate post, there is simply too much. This deserves a separate post too. That one shouldn't simply repeat Gowers and Scullard's notions from 70 years ago, instead, look at the evidence presented by modern research. I apologize for my choice of words. I was sincerely shocked with you not distinguishing one end of South Sudan from the other. It's like equating the Russia–Finland border with the Russia–Ukraine border. Yes, the southern Butana is not that far from the South Sudan–Ethiopia border, however, the South Sudan–DRC border is on the other side of the country, c. 1000 km away, and, more importantly, of a completely different biogeographic zone than the South Sudan–Ethiopia border and the the bulk of the area in between (covering most of South Sudan). I believe I'm repeating myself. Which is yet another argument against the notion that forest elephants colonized all of Africa within only a few thousand years. Quite the contrary: I'm arguing they would not travel to the Congolese border, or India for that matter, to get elephants, no, they would simply source elephants from their own backyard, i.e. the Butana and its surroundings. Likewise, we know the Ptolemies catched elephants in Sudan and Eritrea and Carthage got them from the Atlas region, not from Sierra Leone. Excuse me? Interestingly, you wrote only two months ago: To which I then answered: African war elephants were either L. cyclotis (as suggested by Gowers and Scullard about 70 years ago) or L. africana (as supported by recent DNA analysis). Neither L. a. pharaonensis nor any other unattested subspecies is a serious alternative.

-

Great, many thanks for the clarification!

-

What is the advantage of embedding? Why not simply use e.g. Firefox's? Also, I noticed the libraries/source/spidermonkey/ folder in the svn development version is already 3.3 GB. For comparison, the public mod is 4.2 GB and the .svn folder, i.e. the entire revision history since the start, is 5.8 GB. Why is the SM folder so large? Firefox incorporates the most up-to-date version of SM (doesn't it?), but is only c. 64 MB to download and c. 250 MB installed size. Great! I like your ambition! The more up to date software is, the better! However, I read SM68 requires C++14 and SM78 uses C++17, so I guess that'll require a lot more work?

-

@Stan`, when adding new portraits to the public mod, could you add folders under art/textures/ui/session/portraits/units/, one for each civ, as is already the case in actors/units/ ? Ideally each actor would have its own icon, so subfolders could help keeping things manageable, and have matching file names.

-

Generally I like consistency. However, for hero portraits specifically, I think it's far more important they look good, are recognizable, and stand out. I would strongly recommend against basing hero portraits on actors in game; to me all soldiers look rather similar (possibly because I always play maximally zoomed out). I like the Boudicca and Nastasen portraits, not because their high detail, but because of the contrast between background and portrait; moreover, their bright background really differentiates them from the icons of other entities. As such, I recommend giving all hero portraits, or at least each hero of a civ, a clearly differently coloured background.

-

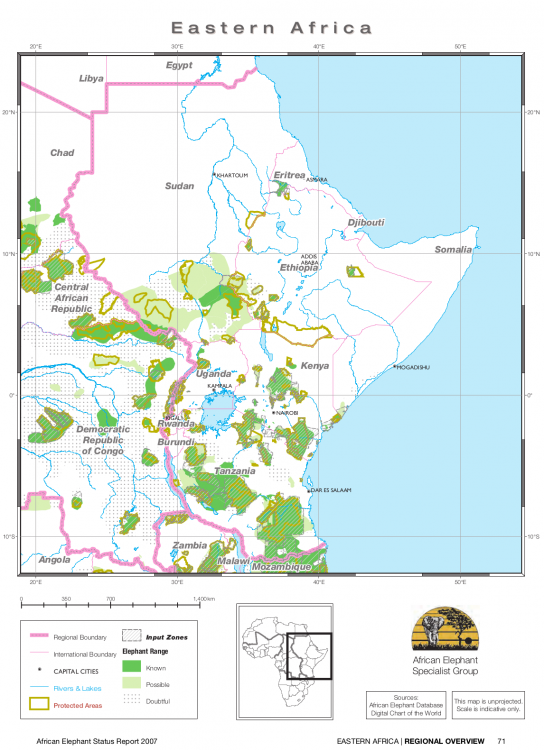

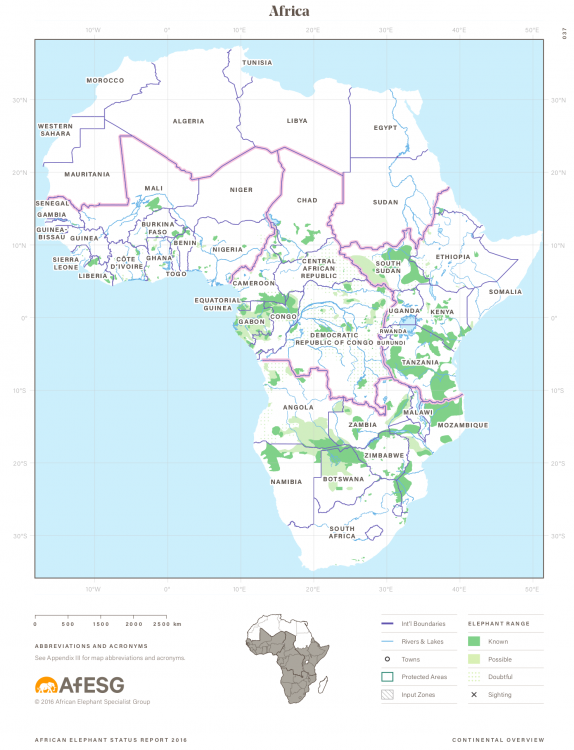

Well, I certainly don't fully agree with every single point all those articles make. However, that's how modern scholarship works: look up the actual sources, read critically what others think, engage in discussions, form your own opinion, then publish (or post on a forum ). As I wrote earlier, I disagree with Gowers and Scullard's point, which has since become the communis opinio, that the Carthaginians and Ptolemies used forest elephants (L. cylcotis). For this to work, one has to make various assumptions, nor is there real evidence in support. By contrast, the idea that they used (small) bush elephants (L. africana) is a much more simpler explanation. Now the names “bush elephant” and “forest elephant” may be a bit misleading. While forest elephants live in the equatorial rainforests of West and Central Africa, they're not afraid of grass. As for the bush elephants, savannas are not completely treeless, and herds of bush elephants inhabiting woodlands have been found throughout Africa. Elephants actually like trees, they offer shade (and food). You mean Pliny Naturalis Historia 6.185: herbas circa Meroen demum viridiores, silvarumque aliquid apparuisse et rhinocerotum elephantorumque vestigia. ipsum oppidum Meroen ab introitu insulae abesse LXX p., iuxtaque aliam insulam Tadu dextro subeuntibus alveo, quae portum faceret. The ‘greener grass and a bit of forest’ is in contrast to the desert between the 1st and 6th cataracts, described only slightly earlier (6.181, 6.182). Here is a recent study of the (now isolated) elephant population of Eritrea: A. L. Brandt et al. (2013) “The Elephants of Gash-Barka, Eritrea: Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Patterns” https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/est078 which shows that Eritrean elephants are genetically bush elephants and clearly not forest elephants. Moreover, the area the live in is actually adjacent to the Butana (i.e. the “Island of Meroë”) in neighbouring Ethiopia and Sudan, and matches Pliny's description (arid, but with grass, trees, and elephants). This sentence is rather misleading. I'm assuming good faith, i.e. that's not deliberate. Please have another, more careful look at an appropiate map. As you know, the Butana is the area between the Blue Nile and Atbara (or Black Nile); its lower, northern part is in Sudan, the upper, southern in Ethiopia. Adjacent to it is the Gezira, the area between the Blue Nile and White Nile. On the other side of the White Nile is Kordofan. To the south is the Sudd, a large swamp along the White Nile, which was known to and reached by Egyptians, Romans, and Arabs, but considered impregnable (I guess this also formed a natural border for the Meroitic and later kingdoms); the Sudd is now in South Sudan. Beyond the Sudd is a transition zone, and only afterwards you reach the forrested Congo-South Sudan border, more than 1000 km away from the Butana. Actually we do, one just needs to understand Africa has several distinct ecoregions (I've listed them over here). While the exact size and location of those ecozones has changed over the past thousands of years, the qualitative picture is basically the same. For elephants specifically, forest elephants live in the tropical moist forests stretching from Guinea and Sierra Leona to the Democratic Republic of Congo. In the forest-savanna mosaic, or at least the part along the Congolese border, both forest and bush are known, and possibly hybrids too. However, in the East Sudanian Savanna, the Sudd, and the rest of East Africa there are no forest elephants, only bush elephants. For where elephants live nowadays live in East Africa, see this map from J. J. Blanc et al. (2007) “African Elephant Status Report 2007 : An update from the African Elephant Database” https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/9022: And one of Africa from the 2016 update: To summarize, the elephants surviving today in Mali, Chad, practically all of South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea are all bush elephants, not forest elephants.

-

For maps situated in Africa, it's important to realize the continent consists of several distinct ecoregions (get a decent map or consult Wikipedia (linked). From north to south: Mediterranean zone (used to be fertile): coastal Morocco to Egypt. Atlas Mountains (wooded): Morocco to northern Tunisia. Sahara (desert): Mauretania to Egypt. Sahel (transition zone): Mauretania to Sudan. Sudan (savanna): West Sudanian savanna: Senegal to Northern Nigeria; North Central savanna: southern Chad, northern Central African Republic, western South Sudan; East Sudanian savanna: Uganda to Eritrea. The Sudd (swamp along the Nile in the centre of South Sudan) separates the savanna regions. Forest-savanna mosaic (nomen est omen): Guinean: Senegal to Cameroon; also includes the Dahomey Gap; Northern Congolian: Cameroon to South Sudan. Tropical moist broadleaf forests (I doubt anyone would ever use this technical term in daily language): Upper Guinean forests: Guinea and Sierra Leone to Togo; Lower Guinean forests: Benin to Cameroon; Atlantic Equatorial coastal forests: Cameroon to Democratic Republic of Congo; Northwestern Congolian lowland forests: Cameroon to DRC; Congolian rainforests: Cameroon to DRC. The above is roughly the situation north of the equator. Below the equator you get practically the same ecoregions, though in reversed order, under different names, in different countries. The different ecoregions are actually identifiable from space: Of course, it's easier on schematic maps: These vegetation zones correlate (i.e. not a 1:1 correspondence) with climate: precipitation (rainfal): temperature: and, to a lesser extent, even language families:

-

@StarAtt, hello and welcome to the forums! You might want to have a look at these posts: https://trac.wildfiregames.com/wiki/Alpha24 https://wildfiregames.com/forum/index.php?/topic/28286-0-ad-development-report-september-2019-–-may-2020/ https://wildfiregames.com/forum/index.php?/topic/27385-0-ad-svn-gameplay-patches/&tab=comments#comment-390076 Some of the things you listed as changes are not actually changes, e.g. The “diminishing returns” mechanic was introduced years ago, was simplified in 2016, and has not changed since then. What's done this alpha is that the tooltip was updated. Many other tooltips and user-facing text strings are reviewed, standardized, and updated as well. They never had an extra mine. This is simply a false entry removed from the kush.json civ file. The civ files are outdated and still contain misinformation, cleaning them up and correcting them is on the agena, so you can expect more of these ‘non-changes’. D2792 / rP23800 (which was actually reviewed and accepted by you, @badosu).

-

https://code.wildfiregames.com/D1323

-

@Sundiata, some more articles on African war elephants, first a few old ones: W. Gowers (1947) “The African Elephant in Warfare” https://www.jstor.org/stable/718841 W. Gowers (1948) “African Elephants and Ancient Authors” https://www.jstor.org/stable/718306 H. H. Scullard (1948) “Hannibal's Elephants” https://www.jstor.org/stable/42663097 W. Gowers & H. H. Scullard (1950) “Hannibal's Elephants Again” https://www.jstor.org/stable/42661466 Then several published more recently, a few already of which were already mentioned earlier in this thread: L. Casson (1993) “Ptolemy II and the Hunting of African Elephants” https://www.jstor.org/stable/284331 J. F. Shean (1996) “Hannibal's Mules: The Logistical Limitations of Hannibal's Army and the Battle of Cannae, 216 B.C.” https://www.jstor.org/stable/4436417 M. B. Charles (2007) “Elephants at Raphia: Reinterpreting Polybius 5.84–85” https://www.jstor.org/stable/4493501 M. B. Charles & P. Rhodan (2007) “Magister Elephantorvm: A Reappraisal of Hannibal's Use of Elephants” https://www.jstor.org/stable/25434049 M. B. Charles (2008) “African Forest Elephants and Turrets in the Ancient World” https://www.jstor.org/stable/25651736 Ph. Rance (2009) “Hannibal, Elephants and Turrets in Suda Θ 438 [Polybius Fr. 162⁻] — an Unidentified Fragment of Diodorus” https://www.jstor.org/stable/20616664 M. B. Charles (2014) “Carthage and the Indian Elephant” https://www.jstor.org/stable/90004712 M. B. Charles (2016) “Elephant Size in Antiquity: DNA Evidence and the Battle of Raphia” http://www.steiner-verlag.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Steiner/Zeitschriften_Historia/Historia_2016_1_53-65_Charles.pdf B. F. van Oppen de Ruiter (2019) “Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art” https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/4/160/htm There are more, of course. Personally I'd highly recommend Casson (1993), if you've not read it already. For those of you without access to an university library, the last two are freely accessable, the rest is available at JSTOR, which allows some limited access, but you can also get them via https://sci-hub.tw/, of course.

-

Practically all domestic ducks are mallards; this paticular photo is from the so-called “Indian runner duck” breed, but it's the same species.

-

A few more images that could be helpful, first a few side views (note the distance between front and hindlegs, the length of their hindlegs, and the size of their tail): Some skeletons: Some skulls: And their historic range (green): Keep in mind it's possible to view things in game from any angle. No, not at all. I listed them in the order I'd prefer to see them added, however, that's just my two cents. It's completely up to artists to decide what they want to work on, and when. One other thing, sexual dimorphism varies greatly from species to species. Often it's not very pronounced (e.g. wolves, horses, camels, tigers), but sometimes different actors are needed (e.g. cattle, elephants, lions). For the bison, the differences are not that great, bulls are a bit larger and have differently shaped horns, but nothing that's really noticeable from a distance, so one version is sufficient. However, many deer species have clearly visible differences (size, fur, antlers) and may need two or three versions: male (stag, buck), female (doe), and young (fawn).

-

Armour, highly unlikely. Riders, reins, baskets, goods, etc., yes. Bactrian camels would (should) be used by the Han Chinese and Xiongnu traders, like the dromedary camels used by the Carthaginians and Persians in game. (Off-topic, actually hybrid camels, i.e. offspring from crossing Bactrian and dromedary camels, were preferred in the Near East. They were bred around Afghanistan, but remains have been found from India to Serbia, indicating their widespread usage in trade networks. Likewise, mules, i.e. infertile offspring from a jack (male donkey) and mare (female horse), were bred around the Mediterranean and considered pack animals superior to both donkeys and horses.)

-

Your duck looks great! While in reality ducks can dive, swim, and fly, what matters for 0 A.D. is their walking animation, like the chicken or peacock, because otherwise units can't catch and kill them for food, which is the main purpose of animals in game. Unfortunately amphibious entities are not (yet) possible, it would also be great to have for e.g. crocodiles and hippopotamuses. As for colour variation (i.e. textures), the one with the green head, brown chest, and light body is most iconic, but those are always adult males: Females are brown: As are young adults, both female and male (you can see they're young because their feathers are not fully grown): Ducklings have a different colour pattern and are covered in down: However, there are also entirely white ducks: And many colour variations in between: Finally, where in the world mallards live: Given the nature of 0 A.D., I don't think it's worth it creating ducklings or young adults; having just one mallard shape + animations is good enough. For textures, I'd recommend having at least three: brown, multi-coloured, and entirely white, in a 3:2:1 ratio. More texture variation would be welcome, but is not a priority, and could always be added in the future.

-

See https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/ Assets in the public domain (“CC0”) or licensed under CC BY (attribution) or CC BY-SA (attribution and share-alike) can be used. Things released under NC (non-commercial) or ND (no derivatives allowed) can't.

-

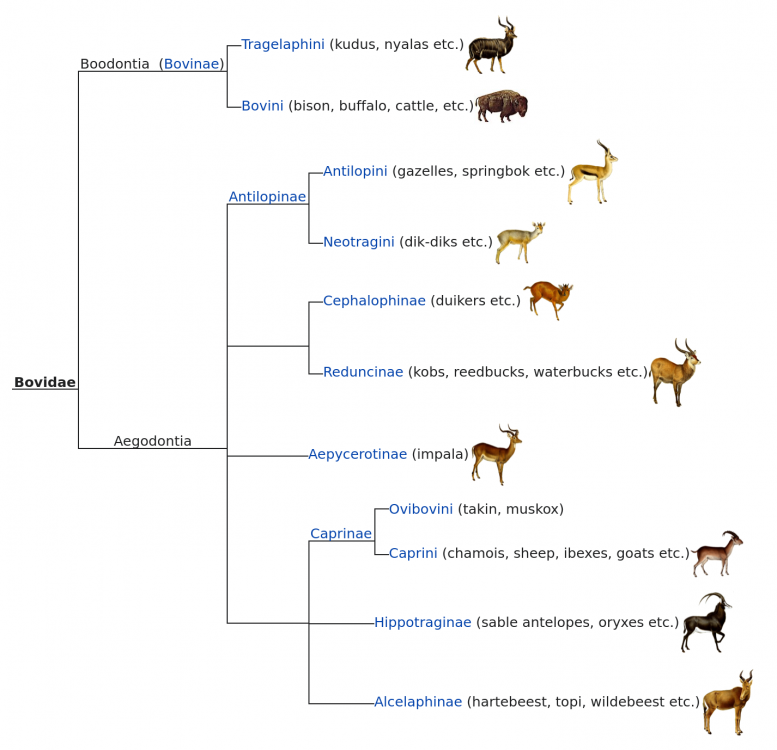

Great! I'd love to see more animals. Since the introduction of cattle last year, in my opinion the most important animals missing in 0 A.D. from a socio-historical point of view are: ducks, especially the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) geese, especially the greylag goose (Anser anser) Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) 0 A.D. also has a deer, but it's unclear which species it is. There exist dozens of deer species, ideally 0 A.D. would have several, or at least the most important: The fact that 0 A.D. is situated in Eurasia hasn't prevented the addition of muskoxen (native to Canada) or black bears (native to North America), though, so I'd say the American bison is welcome too, as are animals from other parts of the world. Despite their name, muskoxen are closely related to goats, sheep, and takin. For the difference between Bovidae (bovids), Bovinae (bovines), and Bovini (cattle family), this cladogram from Wikipedia might be helpful:

-

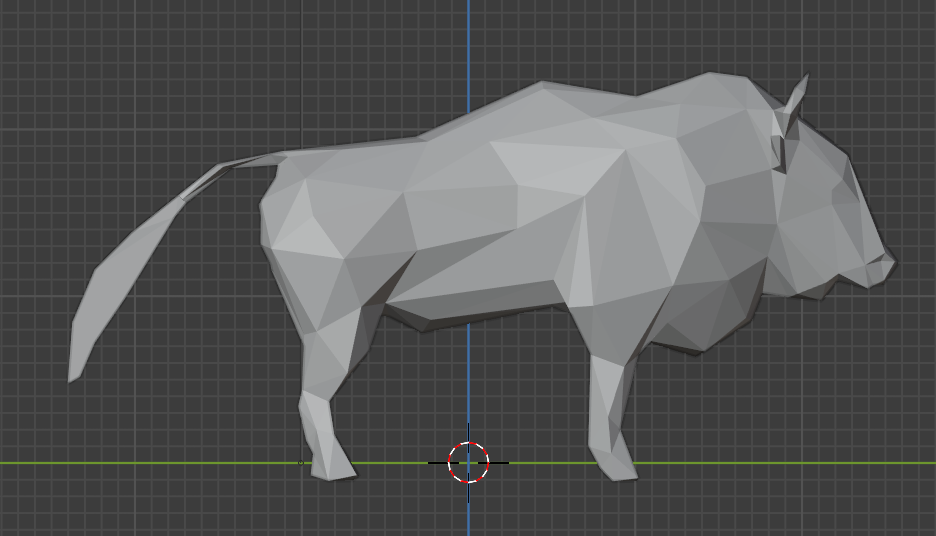

It looks promising! Yes, Wikimedia Commons usually has many nice images, in this case https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Bison_bonasus I'm certainly no expert, but to me it seems wisents have a more-or-less horizontal back and belly and a large hump at their shoulders: Yours, in contrast, seems to have an upward-pointing back and belly and two humps but a hole at the shoulders: