-

Posts

2.300 -

Joined

-

Days Won

23

Everything posted by Nescio

-

Another image, to make the difference even clearer range_comparison.svg: black: a structure with a footprint of 120×60 (wonders in 0 A.D. are up to 60×60) blue: range calculated from edge (proposal?), in steps of 20 red: range calculated from centre (current situation), in steps of 20

-

===[TASK]=== Greek Unit Texture (General Thread)

Nescio replied to wackyserious's topic in Official tasks

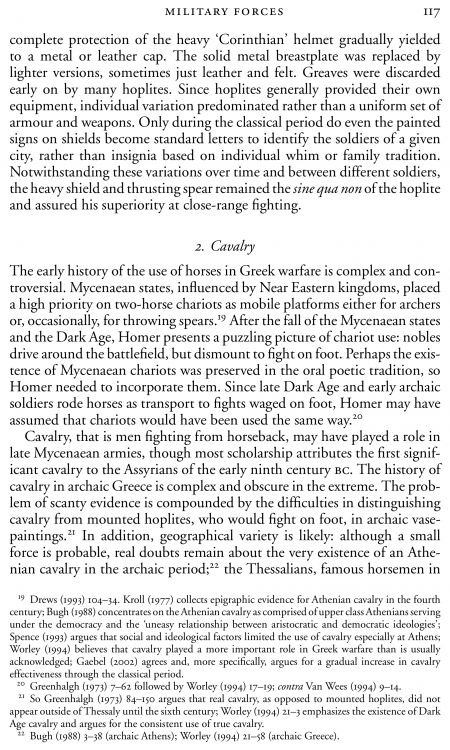

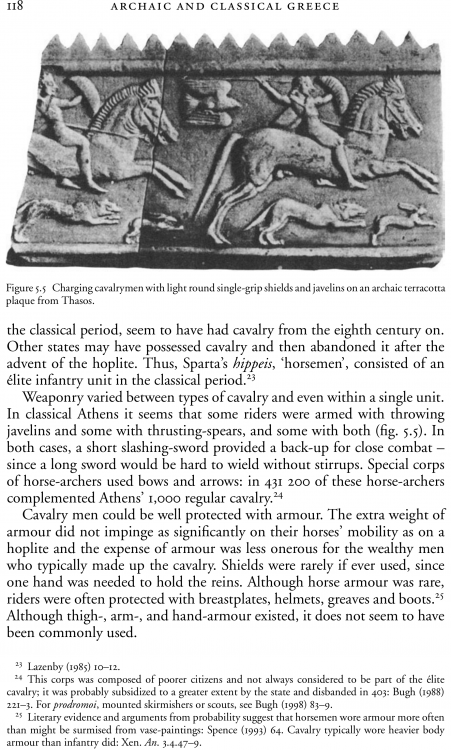

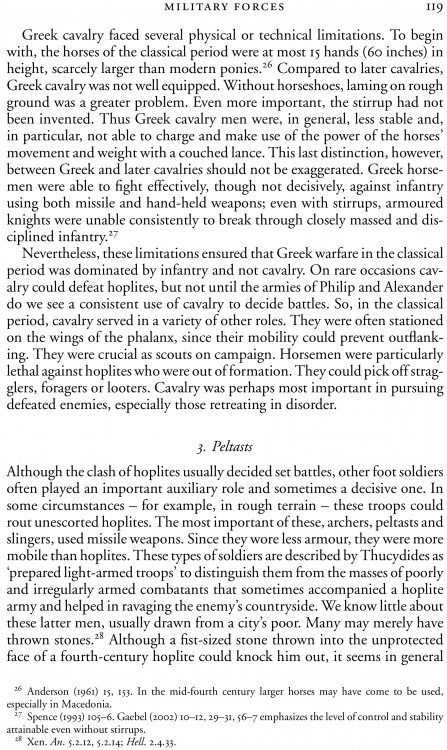

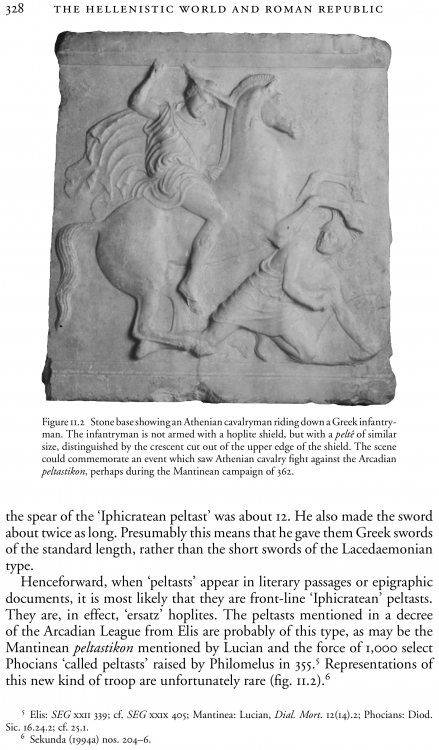

Doubtful. I don't think any classical Greek (i.e. athen, mace, spart) cavalry had shields. (Greek pottery tends to depict mounted hoplites, who fought on foot.) The situation is different for non-Greek cavalry (Paeonians serving under Philip and Alexander where known to have shields). During Hellenistic times (i.e. ptol, rome, sele) some Greek cavalry types adopted (large) shields (aspis or thureos, not peltē). Horse armour appeared as well, though probably the exception rather than the rule (hence reserve for ptol and sele champions). As for classical Greek horseman equipment, the most important source is probably Xenophon, On Horsemanship 8: http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&query=Xen.%20Eq.%2012&getid=1 Here are also four relevant pages from The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare (Cambridge 2008): And an ancient fresco of a charging hetairos (Macedonian companion cavalry): How about the following? basic: tunic, hat advanced: simple helmet, long sleeves, perhaps some body armour elite: helmet, boots, body armour, pteruges, perhaps left arm protected by a cheir (arm-guard, Latin manica) -

The Problem with Sword/Spear Units

Nescio replied to Thorfinn the Shallow Minded's topic in General Discussion

Indeed, with differentiation I do not mean enforcing specialization; hard bonus attacks are ugly and ought to be avoided. With differentiation and more unit types I simply mean units with different values; e.g. Rome ought to be able to train both hastati and principes, the latter of which has higher resistance and metal costs (chain mail), but is otherwise identical; likewise, Macedon ought to have Macedonian (lancers), Thessalian (spearmen), Paeonian (javelineers with shields), and Odrysian (javelineers without shields) cavalry; they all have different statistics, yet perform the same function. Currently all soldiers have the same costs and training time (infantry 50 food, 50 other resources, 10 seconds; cavalry 100 food, 50 other resources, 15 seconds), despite very high differences in damage per second: javelineers 12.8, swordsmen 7.3, spearmen 5.5, pikemen only 2. Add to that a 20% cost and time reduction of Celtic structures and it is no wonder people want to play Britons and not Macedonians. To facilitate a systematic approach it is important to start from a clean and consistent situation; that's what my patches have mostly focussed on. (Getting people to review, accept, and commit them is the hard part.) Another simple idea is keeping units trained at the civic centre of basic rank, while increasing those from the barracks to advanced rank. In my opinion Age of Empires II is a great example of what 0 A.D. shouldn't do. What would already be a great first step is if the formations already present in 0 A.D. would give minor bonuses; e.g. a square or line would increase resistance by one level, while a compact syntagma or testudo adds two levels, but reduces movement speed. Doubling the training time of ranged troops and twice the population for cavalry would already go a long way towards more realistic ratios. -

The Problem with Sword/Spear Units

Nescio replied to Thorfinn the Shallow Minded's topic in General Discussion

Everything in that video looks great! The pair of oxen ploughing a field and the click-drag-click road construction and plot assignment are things I'd love to see in 0 A.D. as well. I suspect that game has much higher requirements, though. To be clear, I'm not opposed to unit battle groups, in fact, I'd love to see them in 0 A.D. too. (Though I'd recommend sticking with the historically attested 4:2:1 ratio for heavy infantry, ranged infantry, and cavalry; the Macedonian 256, 128, 64 and the Roman 120, 60, 30 are probably a bit too much; 40, 20, 10 is probably reasonable.) However, competitive players are able to win well before 100 population is reached, and currently the 0 A.D. noticeably slows down in the mid- to late-game, often before 300 population is reached. Anyway, we're drifting off-topic: I agree the “sword beats spear” situation doesn't really make much sense; if anything, it ought to be the other way around. While you're right in stating a disciplined formation ought to be able to resist a cavalry assault, I do believe a rigid pike formation with weapons extending over 6 m in front is more effective in this than a loose formation of swordmen with blades of 0.6 m. Regardless, what I think is needed is more differentiation, not less. Make heavier troops cost more metal, while ranged troops are cheaper but have longer training times. Moreover, introduce more unit subtypes, with different values. Instead of just spear cavalry, have doratophoroi (spear, no shield), thyreophoroi (spear, long shield), and xystophoroi (very long two-handed lances); split slingers in stone-slingers and lead-slingers (longe range, little damage); separate crossbowman ( https://code.wildfiregames.com/D2886 ), camels ( https://code.wildfiregames.com/D2900 ), and chariots ( https://code.wildfiregames.com/D2965 ); make scythed chariots melee units; etc. [EDIT] And another one: https://code.wildfiregames.com/D3080 gives pikemen a bit more range and other melee infantry a bit less. Another idea is giving higher ranking pikemen even more range (e.g. b 8, a 9, e 10), though that requires an artist to model a few pikes of longer lengths. -

The Problem with Sword/Spear Units

Nescio replied to Thorfinn the Shallow Minded's topic in General Discussion

For battalions etc. to work, the engine needs to be able to comfortably support thousands of soldiers, like in Cossacks. That's currently not the case in 0 A.D. A battalion is a military unit in between a company and a regiment or brigade. Greeks liked doubling (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc.). In Macedonian armies, sixteen pikemen formed a lochos (file), sixteen lochoi a syntagma (square, i.e. 16×16=256 men, plus five supernumeraries), which was the smallest tactical unit. Light infantry was organized in files of eight, the smallest tactical unit was a hekatontarchia (nominally 128 men plus five supernumeraries). The smallest tactical unit for cavalry was the ilē (squadron), the textbook example is 64 horsemen, though the number could range from a few dozen to over a hundred, depending on how much cavalry was available in the army (rarely over 10%). Following Aelian, a full phalanx would be 64 syntagmata or 1024 lochoi, i.e. 16384 phalangites. Add to that half that number in light infantry, and a quarter of that in cavalry, and you get an army of c. 30 thousand. In practice the numbers could be even larger; e.g. at the Battle of Raphia (217 BC), both sides fielded armies of c. 70 thousand. The smallest tactical unit of Roman infantry was a centuria (century) of 60–80 soldiers or a manipulus (maniple) of twice that (except for triarii). A cohors (battalion) nominally consisted of 120 velites, 120 hastati, 120 principes, 60 triarii, i.e. c. 450 soldiers. The smallest tactical unit for cavalry was a turma (squadron) of 30. A Roman legiō (brigade) consisted of ten cohorts and ten squadrons, i.e. c. five thousand men. An auxiliary āla (brigade) had (at least) the same number of infantry as a legion, but three times as much cavalry. A Roman army consisted of two legions and two alae, i.e. c. 25 thousand men. While I agree companies, battalions, brigades, etc. would be great to have, I sincerely doubt 0 A.D. could achieve that in the forseeable future, given that entities are not simple sprites, but three-dimensional actors with lots of variation. Even if we reduce the numbers by a factor five, i.e. squadrons of 6, centuries of 12, and squares of 50, then it would still be something for late game only. An early rush with a dozen or so unorganized men could already win a game. -

The Problem with Sword/Spear Units

Nescio replied to Thorfinn the Shallow Minded's topic in General Discussion

For Hellenistic warfare specifically, the following nine troop types are listed by Aelian Tactica §2, which is largely similar to Arrian Tactica §2–4 and Asclepiodotus Tactica §1 (all three go back to a (now lost) treatise of Poseidonius, which in turn is based on an (also lost) Tactica by Polybius): infantry: hoplites, i.e. heavy infantry, equipped with (partially) metal armour, greaves, heavy shields (aspis), and long spears or pikes peltasts, equipped with lighter armour, boots, smaller shields (peltē), and shorter spears; hence more mobile psiloi, i.e. light infantry (archers, javelineers, slingers, and those that throw rocks by hand); no armour, greaves, or shields cavalry: lancers javelin cavalry horse archers cataphracts, i.e. armoured horses chariotry elephantry As for the length of thrusting spear and pike, it varied over time (the values are only approximates, obviously): classical hoplites: 8 feet → 2.56 m Iphicrates' peltasts: 16 feet → 5.12 m Alexander's pikemen: 10–12 cubits → 4.80–5.76 m pikemen c. 300 BC: 16 cubits → 7.68 m Late Hellenistic pikemen: 14 cubits → 6.72 m See Christopher Matthew “The Length of the Sarissa” Antichthon 46 (January 2012) 79–100 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0066477400000150 for more details. The main source for Iphicrates' reforms is Diodorus Siculus Library 15.44.3: http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Diod. Sic. 15.44.3 Indeed. The relevant section is Polybius Histories XVIII.28–32: http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Polyb. 18.28 http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Polyb. 18.29 http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Polyb. 18.30 http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Polyb. 18.31 http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekTexts&getid=1&query=Polyb. 18.32 Basically, as long as the phalanx holds, it can withstand and drive back anything in front of them, but when it breaks (e.g. due to uneven terrain), it becomes vulnerable and the more manoevrable Romans can make mincemeat of them. -

The Problem with Sword/Spear Units

Nescio replied to Thorfinn the Shallow Minded's topic in General Discussion

Everyone, a note on terminology: unless explicitly stated otherwise, “light” means “ranged” and “heavy” means “melee” (i.e. troops that fought in formation). The terms refer to their rôle on the battlefield, not to the heaviness of their arms and armour, as some people mistakingly assume. A few modern authors also use the term “medium” for troops that could fulfill both functions, though that term is not as widespread. This observation is worth a bit more attention. There is more than one reason for this. Firstly, it's indeed mostly true: light troops indeed had much the same function: raiding, skirmishing, chasing off enemy skirmishers, harassing enemy troops with projectiles to force them to raise their shields and stay put, and killing off fleeing opponents; whether they're armed with javelin, sling, bow and arrow, crossbow, musket, or rifle is of lesser importance—that does not mean there are no differences, though. Secondly, battles were typically decided by the main battle formation (i.e. heavy infantry) or a (heavy) cavalry charge, so other troops deserve less attention. Thirdly, light troops were typically of lesser social status, therefore of less interest to authors and their public; reading and writing were very much elite activities. Likewise, servants and slaves are rarely mentioned in texts, even though we know they were present in large numbers. For instance, in Classical Greek warfare, most citizen hoplites had a servant each with them. By contrast, in the Macedonian army of Philip and Alexander, eight pikemen only had one servant between them; about the same ratio was true for imperial Roman legionaries. Source, please? Picking a spear, wrapping a leather thong (the ἀνκύλε ankyle or āmentum) around it, holding it in the right place, choosing a target, lifting your arm, then throwing it, releasing the javelin while keeping hold of the strap—I fail to see how this is faster than picking a pebble from a purse and slinging it, or placing an arrow on the bow and pulling back the string. Crossbows, arquebuses, muskets etc. are indeed a lot slower. They're adopted nonetheless because they require much less skill to use; when aiming and shooting you expose less of your body than when using javelin, sling, or bow and error; and they can be reloaded when hiding behind shields or walls, making them especially suitable for siege warfare. It's a bit more subtle than that. I wrote about it earlier in more detail (see this post). Xenophon Anabasis 3.3.16–17: Though you're right slings were cheap (basically a strip of clocth), slingers were specialists. Also, “elite slingers” is a bit of an oxymoron: they were of low social status and came from poor families in rural areas, but had a lifetime of experience with the sling: boys herded livestock from a young age, using slings to keep the herd together and fend off wolves etc. When more than one son survived into adulthood (infant and child mortality were very high in pre-modern times), only one could inherit what little property the family had, therefore to avoid poverty and have a chance at a better life, the others went abroad to serve as mercenaries. There was no such thing as an “unskilled slinger”. Archers were specialists too, though of a higher social status. The bow and arrow is very much an elite weapon: composite bows and strings were delicate weapons, requiring high skill to make and maintain, therefore not cheap. Moreover, archery requires years of practice, which means skilled archers could only be people who had plenty of free time (typically a leisure class whose lands were worked by others). To the best of my knowledge, the staff sling (fūstibalus) belongs to Late Antiquity and Early Medieval Period, i.e. postdating 0 A.D.'s timeframe; they would be a nice addition to Millennium A.D., though. Also, mass conscription is something of modern times. In Antiquity, economic power, military power, and political power were correlated. In Greek city states, only citizens with at least a certain amount of wealth were expected to serve on campaigns, i.e. those with enough land and income to own a pair of oxen, who served as hoplites (heavy infantry). The richest supplied the cavalry (or paid others to ride their horses, while they themselves fought on foot as hoplites. Poorer people could volunteer, but were generally not expected to fight, except in emergencies (the same applies to slaves and children)—Sparta and its helots is an exception. Light troops were often mercenaries (i.e. foreigners and specialists). -

See the in-game manual: . (Period): select idle worker / (Slash): select idle warrior \ (Backslash): select idle unit The keys are actually customizable; see the default.cfg file. This is solved in the development version (A24): 23921

-

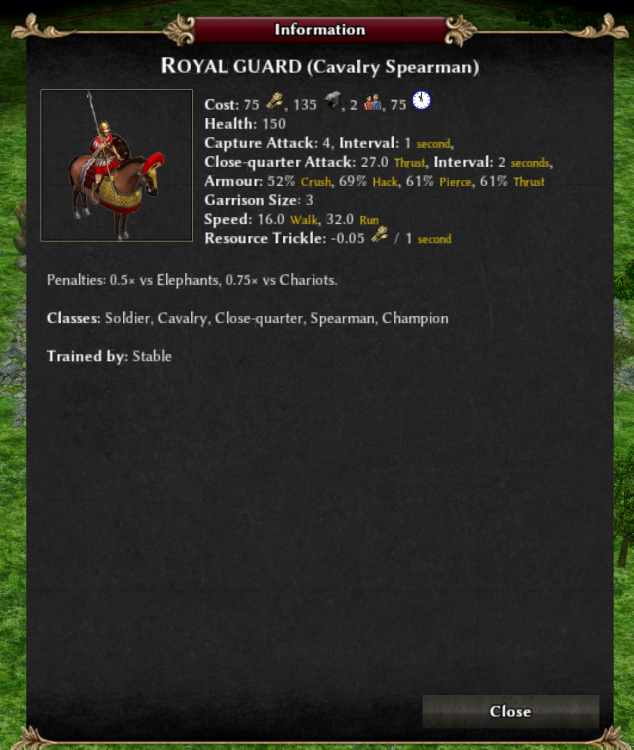

Rise of Nations had units suffer from attrition damage when in enemy territory (like 1 health per second), unless within range of a friendly supply wagon. It would be nice to have that mechanic in 0 A.D. too. @Freagarach? Actually 0 A.D. used to have health decay (rP10034), but this was replaced with the current capture points territory decay when structure capturing was introduced (rP16550). Resource trickle is displayed in tooltips: But yeah, the top panel could use a redesign, displaying not only the amount of resources you have, but also the trickle total.

-

What I did in my 0abc mod is simply give units a negative food trickle rate.

-

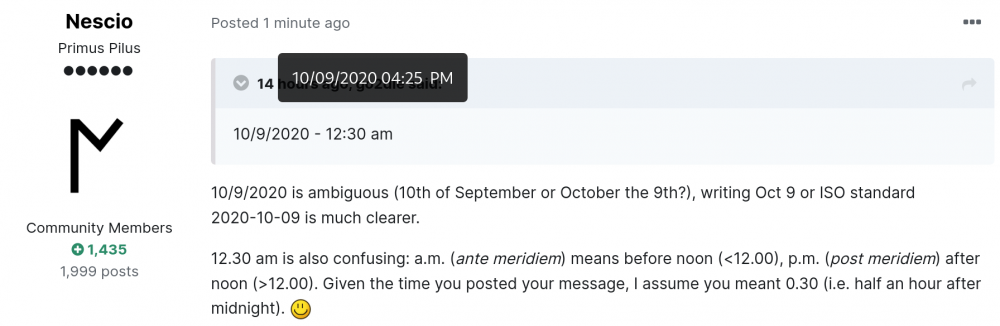

In the entire English-speaking world, the comma is the thousands separator and the point the decimal separator—unlike most of Europe, where it's usually the other way around. (Personally I prefer a non-breaking space.) Whilst the USA has a large footprint and American spelling is becoming increasingly dominant, American standards are not automatically the international default; most of the world uses the metric system and the A4 paper format, for instance. Likewise, day-month-year is far more common than month-day-year: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Date_format_by_country#Usage_map At least as important as how common something is, is that unnecessary ambiguity ought to be avoided. Whilst the a.m./p.m. system is easy to learn, not everyone is equally familiar with it (I've encountered several people over the years who misunderstood it), whereas the 24-hour format is immediately and correctly understood worldwide. Likewise, 10/9 and 9/10 are less clear than Oct 9 or 9 Oct. Wikipedia uses 13:57, 9 October 2020; github 9 Oct 2020, 13:57; both are based in the USA. The United Nations (headquarters in New York) uses 9 October 2020 as well.

-

Thanks, however, in quotes it's still 14/10 and those have 9:20 AM again. Moreover 2,011 has become 2.011. en_GB was probably better. Ideally the month name would be written out or abbreviated; e.g. in Java, MM produces 10, MMM Oct, MMMM October. I gather a custom forum locale is not possible?

-

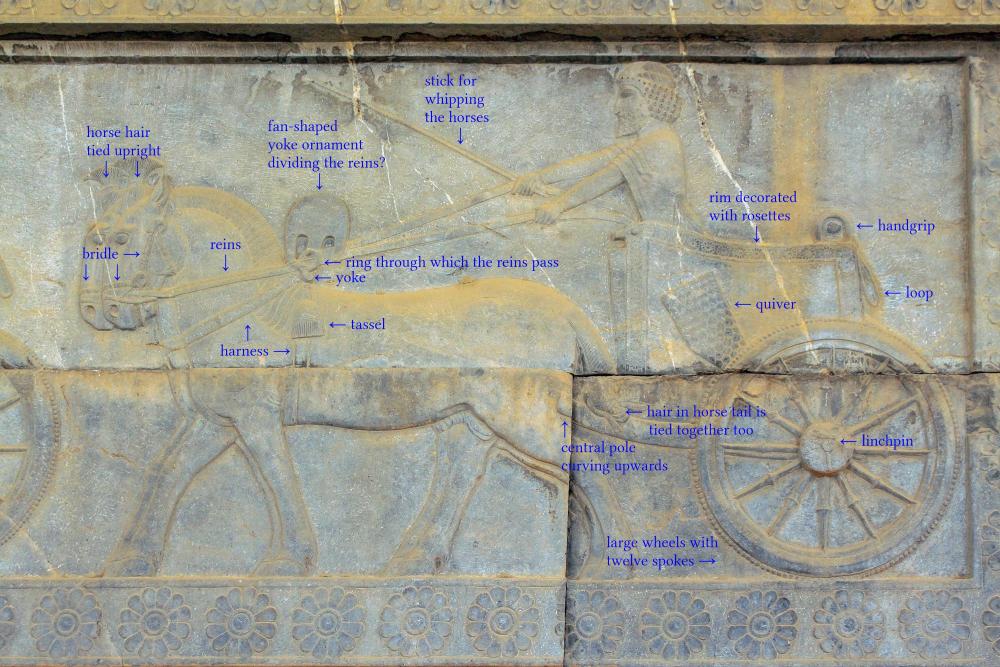

Yes, four is better than two. From Persepolis we have highly detailed reliefs of Persian chariots. I've annotated one (click and zoom in): For the yoke, this fragment, now in the British Museum, might be clearer: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1818-0509-2 However, they're en profile and depict two-horse chariots. For a four-horse Persian chariot and the ropes tying the horses to the chariot, see the Alexander mosaic. No depictions of scythed chariots have survived, so we have to rely on the descriptions by Greek authors, e.g. chiefly Xenophon https://wildfiregames.com/forum/topic/31414-reference-chariots/?tab=comments#comment-407885

-

As stated earlier, no depictions of scythed chariots have survived. However, we know from (Greek) texts they existed. The Anabasis is Xenophon's account of the journey of the Ten Thousand (401–399 BC), in which he participated. Another major work by Xenophon is the Cyropaedia, his work on Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire; part fiction, part history, part moral philosophy (it was written around the same time as Plato's Politeia (The Republic)—not a coincidence). Anyway, after conquering Babylon, Cyrus is preparing to invade Lydia, and invents the scythed chariot (Xenophon Cyropaedia 6.1.27–30):

-

Three pottery fragments, made in Athens, found in Egypt, now in the British Museum, depicting Greek four-horse chariots and showing only the inner pair was connected to the central pole, the outer two were tied with ropes and could run more freely: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/X__5031 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1886-0401-1289 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1886-0401-1202 The same is true for (later) Roman chariots, as well as 19th C quadrigae inspired by them (e.g. Brandenburger Tor in Berlin, Arc de Triumph Caroussel in Paris, Wellington Arch in London, Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow).It should be noted Greeks and Romans used chariots for racing, and not on the battlefield. However, the Chinese war chariots from the Terracotta Army also had four horses, of which only the inner two were fastened to the yoke and central pole (see earlier post).

-

More Assyrian reliefs, all of them now in the British Museum. A three-horse chariot, from a palace in Nimrud, c. 860 BC: Two chariots without horses being transported on a boat to cross a river (the Euphrates?); Nimrud, c. 860 BC: Another lion-hunting scene; only one horse is shown, but the number of reins suggest three; also note the large wheel; from Nineveh, 8th C BC: Detail from a chariot: Detail of chariot horses: People on a cart drawn by a pair of oxen, from Nimrud, c. 728 C BC: Assyrian early cavalry, organized as a chariot team; one man, with helmet and body armour, fires a bow; the other, unarmoured, holds the reins of both horses; Nimrud, c. 860 BC: Assyrian cavalry from over a century later; still a pair, but both men have a lance, helmet, and body armour; Nimrud, c. 728 BC: Finally, Assyrians on foot fighting two Arabs on a dromedary, one with a stick driving the camel, the other shooting a bow; Nineveh, c. 650 BC: (All these photographs are from Wikimedia Commons.)

-

Thanks for the clarification, it's good to know what the bottleneck is. (What is a “drawcall”? Drawing a single object?) How much worse is having e.g. five instead of three variants of a knife for the game as a whole? And would deleting variants from props and actors speed up the game significantly?

-

@Genava55, lovely, thanks a lot! (Spoilers would be nice, though. ) While historic reenactors can occassionally provide valuable insights, popular videos ought to be used with caution. Generalizing and drawing conclusions on the basis of a single sample is a slippery slope. Yes, Egyptian chariots tended to be light and nimble, but equating them to the Middle East goes too far. Just look at some of the examples I posted earlier. Chariots with the axle below the middle of the basket, below the back, or somewhere in between are known from the Near East. Assyrian chariots had rectangular baskets too and crews of two, three, or four. As for the number of spokes, four, six, and eight are common, but seven, nine, ten, and twelve are also known, and probably a few other numbers; if many-spoked wheels were intrinsically better, then surely people elsewhere would have figured that out; the number of spokes appears to be more a local preference, if anything. Wheel diameter wasn't constant either, some had quite small wheels, others were much larger. One has to keep in mind chariots were not mass-produced. More important than those differences are the more fundament similarities: a single axle with spoked wheels and a single pole with horses on either side. Sorry, I'm not quite sure what you meant. Chariots had spoked wheels, but solid wooden wheels continued to be used, e.g. moveable siege towers.

-

Gathering meat is an activity far fewer units are typically involved in than farming or wood cutting. If a player assigns only a single unit to slaughter animals, then only one variant has to be drawn, right? Also, as you pointed out, the prop is rather small, surely that affects performance too?

-

Thank you! However, I noticed 10/09/2020 has now become 09/10/2020, which may confuse some Americans. Is it possible to change this to e.g. “Oct 9” (as used on phabricator), “9 Oct” (as used on github), or “2020-10-09” (ISO 8601 standard), to avoid ambiguity?

-

Lovely, and certainly much better! Did you change the colour of the scythes? They're supposed to be iron. Also, could you add at least two more below the platform? More importantly, the yoke is supposed to be attached to the central pole, and only the central pair was yoked; the outer horses, if any, were fastened with ropes. I've posted various images at https://wildfiregames.com/forum/topic/31414-reference-chariots/?tab=comments#comment-407548 The most useful in this case are those from Assyrian and Persian reliefs. Given that scythed chariots did not exist at the time of Xerxes and the Greco–Persian wars (c. 480 BC), but were present at the Battle of Cunaxa (400 BC), having a non-scythed chariot champion that can be upgraded to one with scythes would be great. That would require more actors, though.

-

No depictions of scythed chariots have survived. However, they are well attested in the works of various Greek historians. Most useful is the description in Xenophon Anabasis I.8.10: The quality of translations varies. Words to look out for in Greek: τό ὄχημα okhēma: anything that bears or supports; carriage, cart, mule-car → not a war chariot τό ἅρμα arma: chariot, especially war-chariot, also racing-chariot; chariot and horses, yoked chariot; team, chariot horses → chariot ἡ συνωρίς sunōris: pair of horses → biga τέθριππος, -ον tethrippon: with four horses yoked abreast → quadriga δρεπανοφορός = δρεπανηφορός drepanēphoros: bearing a scythe → scythed chariot

-

Chariots on Mycenean steles, 16th C BC, now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens: Egyptian hunting from a chariot, facsimile of a fresco from the tomb of Userhat, 15th C BC: Tutankhamun single-handedly smashing the enemy army, from his tomb, 14th C BC: Ramesses II on a chariot on relief from Abu Simbel, 13th C BC: Two-horse, three-man Hittite war chariots, drawn from Egyptian reliefs: Chariot model, Early Iron Age, Eastern Geogia: Assyrian king hunting lions, relief from Nineveh, 7th C BC: Assyrian two-horse, four-man war chariot on a relief from Nineveh, 7th C BC: The Etruscan Monteleone chariot, c. 530 BC, which survived intact, and is now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (I'd love to see this in game, perhaps for a Roman hero?): Four-horse chariots depicted on the Greek Vix krater, c. 510 BC: Darius on a chariot hunting lions, Assyrian-style, seal impression: Libyan with biga depicted on the Apadana of Persepolis (c. 500 BC): Persian biga, also from Persepolis (c. 500 BC): The only two-beam and four-horse yoke example I know of, the Achaemenid gold model of a (ceremonial?) chariot from the Oxus treasure, now in the British Museum: Four-horse chariots from the Terracotta Army (246–208 BC), China: Ashoka on a two-horse chariot, as depicted on the southern gateway of the Sanchi stupa in India, c. 1 BC: (All these photographs are from Wikimedia Commons.) I'm hoping @Genava55 and will provide some quality images of Celtic chariots, and @Sundiata for the Kushites. Depictions of Carthaginian war chariots (attested in Greek texts) would be more than welcome too!

-

It is no secret I love to see more chariots in 0 A.D. I've posted about this in various topics scattered over these forums. While the Greeks and Romans no longer used chariots for warfare, many others (e.g. Celts, Carthaginians, Libyans, Kushites, Persians, Indians, Chinese) still did. However, to be able to better understand chariots, it helps to look at the similarities (and differences) between chariots of various civilizations. Hence this thread. First a bit of context. Stone or clay tournettes (precursor of the wheel) from the fifth millennium have been found in the Near East; they were . The true potter's wheel probably existed around 4000 BC. Horses were domesticated somewhere on the Pontic–Caspian steppe (the Indo-European homeland: Ukraine and southern Russia), also during the fourth millennium. The first animal-drawn (ox) carts emerged probably around the same time (Bronocice pot). The oldest surviving wheel and axle (Ljubljana Marshes Wheel) is dated to c. 3150 BC, which most likely belonged to a pushcart. The crucial invention, however, was that of the spoked wheel, which was significantly lighter and thus allowed for higher speeds than the massive solid wooden wheels. The combination of horse, spoked wheel, and composite bow enabled the chariot, which existed in the Sintashta culture by 2000 BC, and spread from there throughout Eurasia, dominating Bronze Age warfare. True cavalry (i.e. troops fighting from horseback), as opposed to mounted infantry (i.e. troops riding to battle on horses, but dismounting and fighting on foot), gradually emerged during the first millennium (1000–1 BC). It did not immediately replace chariotry. True cavalry, mounted infantry, and war chariots continued to coexist for centuries. Chariots fundamentally followed the same design: a single axle with two spoked wheels, a platform or basket above with space for two to four men, and a central pole with a double yoke attached for a horse on either side. Drawings can be clearer than words or photograps: The biga (two-horse chariot) was more common than the quadriga (four-horse chariot); the triga (three-horse chariot) is attested as well (Iliad 16.152, Etruscan art, Roman coins), but was probably not as widespread. It's important to realize the chariot itself was the same: only the inner pair was yoked, the outer horses were fastened with ropes. Chariots with two beams and a single animal (horse, donkey, mule, dog, goat) existed (at least by the 1st C AD) for travelling, but are not known to have been used for warfare, parades, or racing.

-

10/9/2020 is ambiguous (10th of September or October the 9th?), writing Oct 9 or ISO standard 2020-10-09 is much clearer. 12.30 am is also confusing: a.m. (ante meridiem) means before noon (<12.00), p.m. (post meridiem) after noon (>12.00). Given the time you posted your message, I assume you meant 0.30 (i.e. half an hour after midnight). [EDIT] @Itms or whoever is in charge of the forum software, could the format of message that pops up when hovering the cursor over the post time be changed (e.g. “2020-10-09 at 16.25.ss” instead of “10/09/2020 04:25 PM”)? Not everyone is American.