-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

@wowgetoffyourcellphone

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Minimap Icons

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

The wonder should have a star. -

@Stan` we need a parental guide. And implement taunts.

-

-

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/mexico-drug-cartels-recruiting-youths-through-video-games/ar-AAPLkj3

-

Last time I played Among US and the children talking about sex, and many times not all of them are children( They just pretend to be).

-

the problem is how mature our fanbase is and how old are they to behave on the internet.

-

It can be anything even within a country. Even in football ( Soccer) fans to fans (Fanboys) of technology. Any division that leads to the desire to do physical harm or bullying can be dangerous.

-

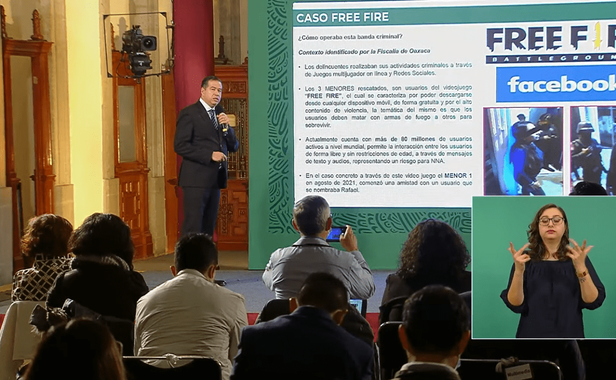

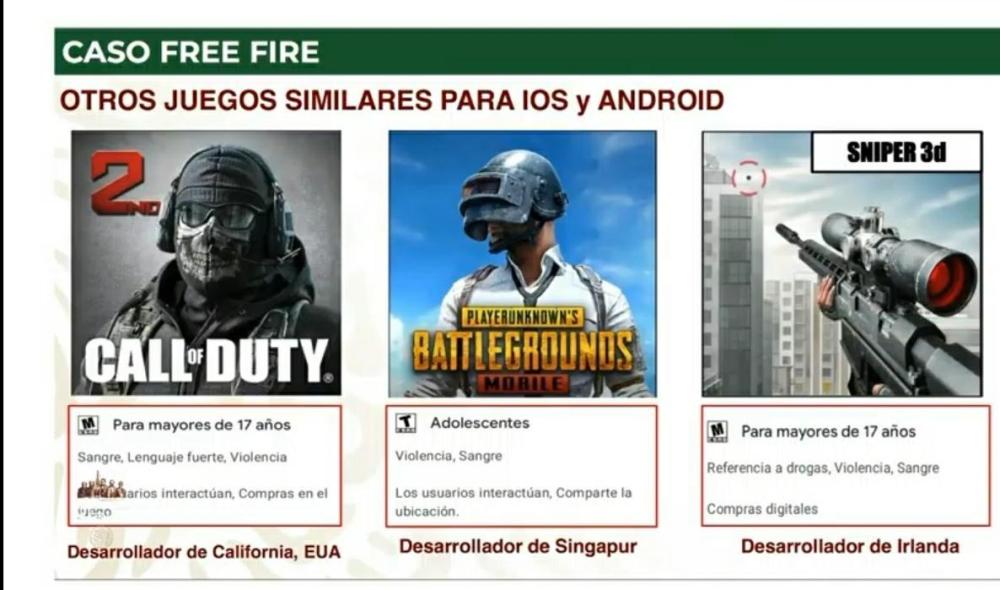

In the AAA, it is even used to recruit children for the Narcos (cartels) in Mexico. then Americans wonder why hard control of the southern border is so important.

-

this is an important point. 2 opposing cultures tend to quarrel.

-

They are cyclical times in history. in these times comes a moral and intellectual decline typical of abundant prosperity. It is when past times are annexed and then come conflicts, whether social or wars and the fall of empires. That is why China is in a cycle where it is very disciplined, even young people do not play more than 3 hours a day. Japan was the same but hey now it's in a demographic winter.

-

This is the little and soft education that is still practiced at this time. Western women and fathers spoil their children a lot.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

0 A.D. Development Report: May - August 2019

Lion.Kanzen replied to Sundiata's topic in Announcements / News

@Stan` -

It is the best. not all of us have the same standard.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Battles in the poverty and the Squalor

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Scenario Design/Map making

when I have time I will. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Battles in the poverty and the Squalor

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Scenario Design/Map making

control the wonder of the center. 5 minutes and win. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Current climate change

Lion.Kanzen replied to Genava55's topic in Introductions & Off-Topic Discussion

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Battles in the poverty and the Squalor

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Scenario Design/Map making

I did a version with a story. I updated the grounds and the armies and structures. I would like to add a triggers to it. -

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/materials-science/buckminsterfullerene