-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

Monuments aka SB2 (special building 2)

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Addition of Han Chinese to 0AD

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

thanks, now another one that I must include in the post of the people under the the of Han. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

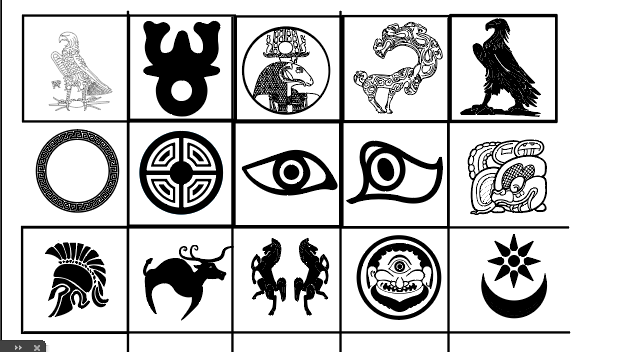

Just the one day we were with Stan, and AlexanderMB We revived and created more than 20 aspid shield designs. Much had to be redone, the originals had poor quality and were already old. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

I have to redo all those designs. -

it is a less "barbaric" version of the nomadic peoples. Much more influenced by Chinese culture, their clothes are less savage more stilized. Even more refined.

- 18 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- nomads

- barbarians

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

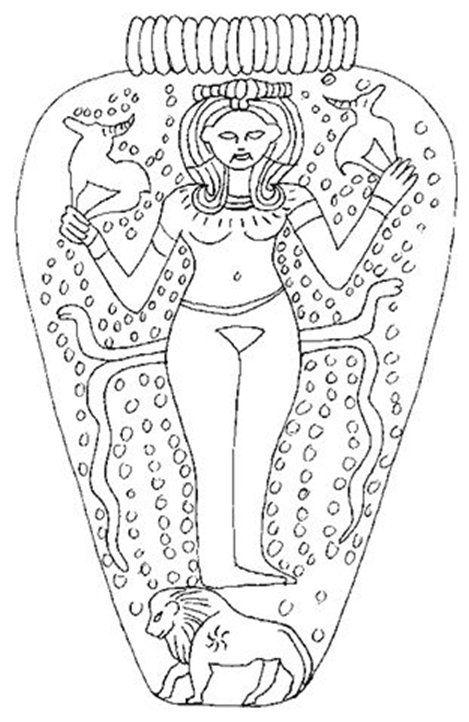

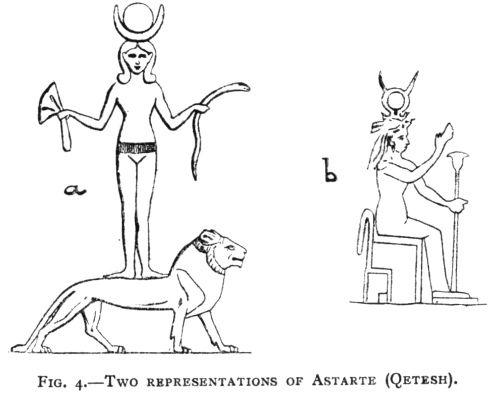

https://matrifocus.com/mythology/tanit-of-carthage/ Tanit, with a pill-box crown, the “polos.” She is dressed in a robe in the Greek style. Her jewelry consists of a glass-paste necklace with graduated beads, and gold earrings. Her arms are in what was probably a “blessing” position, and they have some limited movement. A number of other figurines like this came from Ibiza. Terracotta. Half life-size. Fifth-fourth century BCE. Found in the Punic graveyard of Puig des Molins, Ibiza, Spain (The Phoenicians settled in Spain around 650 BCE.) Archaeological Museum, Barcelona. The heyday of the great temple began when the Carthaginians gained control of the Maltese archipelago in the 6th century BCE. Over the next 300 years, the temple, now belonging to Astarte and Tanit, grew in grandeur and wealth until, in 218 BCE, the Carthaginians lost Malta to the Romans. As was their custom, the Romans identified the local goddess with their Juno Caelestis and expanded the sanctuary on a grand scale, with a monumental gateway and magnificent mosaic floors. This rich and flourishing temple complex was certainly the world-famous sanctuary to Juno that Roman orator Cicero accused Caius Verres of pillaging while governor of Sicily and Malta, between 73 and 71 BCE. Despite Verres’s depredations, the temple survived well into our era, still dedicated to Tanit’s Roman counterpart, Juno Caelestis. The great Carthaginian goddess Tanit is definitely still a puzzle. We do know that she was the tutelary or protector goddess of the city of Carthage, originally a Phoenician colony in North Africa (Aubet 2001: 343). However, scholars are still undecided on the spelling and meaning of her name, her origins, her personality and powers, and, most of all, the question of her having been the prime recipient of child sacrifices at Carthage and elsewhere in the Punic (Carthaginian) and Phoenician world.[2] Tanit,” according to this theory, derived from the same root as Tannin, the snaky, dragon-like sea monster of Canaanite myth and the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah 51: 9; Ezekiel 29: 3-5) (Olyan 1988: 53-54 note 63). The first to make this suggestion was F. M. Cross, and he also argued that Tanit began as an epithet of the Canaanite goddess Asherah (1973:32-33; Olyan 1988: 58) Not surprisingly, most scholars treat Tanit as having come from the Phoenician mainland — as a descendant of one or more of the great Canaanite goddesses. Many think she was a Punic version of Astarte (Hardin 1963:87-88), but in some temples the two were clearly separate deities, though related (Ahlström 1986: 312; Betlyon 1985: 53-54). Some argue that her name is a version of Anat (Hvidberg-Hansen 1986: 178; Albright 1968: 42ff.). A few others see her as either originating in North Africa or being a combination of an indigenous North African goddess with one or more of the Phoenician/Canaanite deities (Ben Khader and Soren 1987: 44-45). An older explanation connects Tanit with the Egyptian goddess Neith (Olyan 1988: 54 note 63). https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neith The English Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge suggested that the Christian biblical account of the flight into Egypt as recorded in the apocryphal gospels was directly influenced by stories about Isis and Horus; Budge argued that the writers of these gospels ascribed to Mary, the mother of Jesus, many peculiarities which, at the time of the rise of Christianity, were perceived as belonging to both Isis and Neith, for example, the parthenogenesis concept shared by both Neith and Mary.[14] However, an ivory plaque solved the problem. The plaque, found in an 8th century BCE temple at Phoenician Sarepta, was dedicated to “Tanit and Astarte.” This constituted the first evidence that Tanit was worshiped in the Phoenician homeland, especially what is now Lebanon (Bordreuil 1987: 81). Before that find, Tanit was thought to be a strictly western and Carthaginian goddess (Aubet 2001: 68). One of Astarte’s titles at ancient Ugarit in Syria and in Phoenicia was Shem Baal (shm b’l) “Name of Baal,” and it is interesting that Pane Baal (pn b’l) “Face [or Presence] of Baal” was a Tanit epithet in Punic inscriptions. It might have indicated that Tanit represented Baal (Hamon) in some way (Seow in Toorn et al. 1999: 322). In addition, in one 5th-century BCE inscription, Astarte was also called Pane Baal (Betlyon 1985: 54). However, Edward Lipiński, who thinks the epithet tnt signifies “She Who Weeps,” suggests that Tanit Pane Baal meant “Pleureuse en face de Baal” — “Weeper in the Presence of Baal” (1995: 2003). Undoubtedly, Tanit and Astarte were closely connected. The details of Tanit’s nature and powers are not really clear. Like Astarte, she had a complex personality (Markoe 2000:130). First and foremost, she was the mother deity of Carthage, protector of the city and provider of fertility. As such she seems to have been a deity of good fortune. Goddess of the heavens, she was often associated with the moon (Benko 2004: 23). Like Asherah, she had maritime connections and was a patron of sailors (Brody 1998: 32-33; Betlyon 1985: 54). There is also some indication that she had a warlike nature, as we would expect of the protector of a city (Ahlström 1986: 311). —same as a Athena, lol— On carvings, Tanit’s presence was often signaled by dolphins or other fish as befitted her patronage of sailors.[5] Fertility symbols also abounded: pomegranates, palm trees, bunches of grapes, grain, leaves, and flowers. Indicators of her celestial connections were the crescent moon and sun. A caduceus entwined with what look like snakes might refer to Tanit as “She of the Snake” or, as one scholar has suggested, it might be a stylized version of Asherah’s sacred tree (Carter 1987: 378). Often, dove-like birds appear (Benko 2004: 24; Moscati 1999: 139). On some stelae an enigmatic open hand might suggest the delivery of a blessing (Azize 2007:196). In addition, Tanit was depicted in winged form in a cult cave on the Spanish island of Ibiza (Lipiński 1995:424-425; Ferrer 1970). Scholars still dispute the conditions under which fetuses, infants, or children were sacrificed to deities. As elsewhere, human sacrifice seems to have been practiced in the Phoenician world in times of crisis (Aubet 2001: 246ff.). However, according to a number of Greek and, later, Christian writers, the Carthaginians regularly sacrificed their children to Baal-Hamon. Later, Tanit also received the grisly offerings. Adding to the gruesome reputation of the Phoenicians, the Hebrew Bible forbade the Israelites from burning their sons and daughters “as an offering to Molech” (2 Kings 23: 10). Such sacrifices took places at sites called “tophets” (Jeremiah 7: 31). A deity named Malik or Malek, probably originally an epithet meaning “king,” existed in the ancient Near East, since the word occurs as a theophoric or “god-bearing” element in names at Ebla, Mari, Ugarit, Phoenicia, and elsewhere (Müller in van der Toorn et al. 1999: 538-542; Lipiński 1995: 227-229; Heider 1985: 401). There is little or no evidence that Malik required human sacrifice. The “Molech” in the Hebrew Bible is likely the same name presented with the vowels of the Hebrew word boshet meaning “shame” (Weinfeld 1972: 149). On the other hand, archaeologists have unearthed sacred enclosures in a number of Carthaginian cities that were extensive cemeteries. They contained the burnt remains of extremely young humans and animals interred in urns and usually marked with stelae, sometimes ornate, sometimes with inscriptions. Many of the inscriptions described the deposit as a molk, now understood as a kind of offering (Weinfeld 1972: 135 ff.). The recipient of molk offerings was originally Baal-Hamon alone and, later, Tanit joined him. Archaeologists began calling the cemeteries “tophets” and interpreting the contents of the urns as burnt sacrifices (Brown 1991: 14; Stager and Wolff 1984: 2). Because so many inscriptions mentioned Tanit, the “tophet” at Carthage became regarded as the “precinct” of the goddess (Aubet 2001: 250). Tanit was then seen as demanding child sacrifice. The cemetery at Carthage was in use from around 700 BCE to 146 BCE. It contained over 20,000 urns holding the cremated bones of young humans and animals, 80% of which were fetuses or neonates (Aubet 2001: 251-252; Schwartz 1993:49). The accepted scholarship agrees with the excavators that the bones are the result of thousands of sacrifices, especially since the inscriptions were mostly votive; that is, they indicated that the depositors owed the deities a return for a favor. An example of such an inscription is: “To our lady, to Tanit . . . and to our lord, to Ba’al Hammon, that which was vowed . . . “ (Stager and Wolff 1984). The interpretation that the vow entailed the infant in the urn may not be correct, but it is generally advanced. The physical anthropologist Jeffrey Schwartz had a different idea about the meaning of the cemetery. He carried out extensive studies of the bones from Carthage’s “tophet.” He pointed out that burials of infants and young children were very rare at Carthage, except in the “tophet,” and that 95% of the burials outside the “tophet” consisted of older children, teenagers, and adults. He concluded that the site was a graveyard for the very young, aborted fetuses, stillborn babies, and newborns who had died of natural causes (1993: 53-56). This explanation makes sense, even in the interpretation of inscriptions. Carthaginian parents would probably have wanted to entrust their dead babies to protective deities, particularly a kindly, motherly goddess, whom they might ask for another child. https://matrifocus.com/mythology/tanit-of-carthage/ -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

there are Sumerian poems that take us back to the queen of heaven Inana. 1-19. When I go, when I go — the mighty queen who ……, who ……; when I, the queen, go to the Abzu, when I, Inana (Inanna), go to the Abzu, when I go to the Abzu, the E-nun, when I go to Eridug (Eridu, Enki‘s patron city) the good, when I go to E-engura, when I go to E-ana (ziggurat residence in Uruk), the temple of Enlil, when I go to ……, when I go to where the great offering bowls stand in the open air, when I go to where the …… pure …… bowls, when I go to where …… is honored, when I go to where Lord Enki is honored, when I go to where Damgalnuna (Ninhursag) …… is honored, when I go to where Asarluḫi (Marduk, Enki‘s son) …… is honored — (Ninurta, his mother Ninhursag, & Inanna in battle dress) When I go into the van of the battle, I go as one who brings forth its brightest light (?). When I follow at the rear of the battle, I go for …… the evil of the ……. 66-69. (Inana speaks:) “Wild bull, face of the Land! I will give life to its man! I will fulfill all its needs (?)! I will make its man produce correct speech in the shrine, …… correct speech in the interior hall of the palace.” 70-77. (The priests (?) speak:) “Oh mistress, let your breasts be your fields your wide fields which pour forth grain! Make water flow from them! Provide it from them for the man! Make water flow and flow from them! Keep providing it from them for the man! …… for the specified man, and I will give you this to drink. I didn't put it in full text. http://www.mesopotamiangods.com/a-sir-namsub-to-inana-inana-g/ http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/inanaitar/ Inana have a contradictory nature. Functions Inana/Ištar is by far the most complex of all Mesopotamian deities, displaying contradictory, even paradoxical traits (Harris 1991; see also Bahrani 2000). In Sumerian poetry, she is sometimes portrayed as a coy young girl under patriarchal authority (though at other times as an ambitious goddess seeking to expand her influence, e.g., in the partly fragmentary myth Inana and Enki, ETCSL 1.3.1 and in the myth Inana's Descent to the Netherworld, ETCSL 1.4.1). Her marriage to Dumuzi is arranged without her knowledge, either by her parents or by her brother Utu (Jacobsen 1987: 3). Even when given independent agency, she is mindful of boundaries: rather than lying to her mother and sleeping with Dumuzi, she convinces him to propose to her in the proper fashion (Jacobsen 1987: 10). These actions are in stark contrast with the portrayal of Inana/Ištar as a femme fatale in the Epic of Gilgameš. Taken by the handsome Gilgameš, Inana/Ištar invites him to be her lover. Her advances, however, are rejected by the hero who accusingly recounts a string of past lovers she has cast aside and destroyed (Dalley 2000: 77ff). Inana/Ištar is equally fond of making war as she is of making love: "Battle is a feast to her" Harris 1991: 269). The warlike aspect of the goddess tends to be expressed in politically charged contexts (Leick 1994: 7) in which the goddess is praised in connection with royal power and military might. This is already visible in the Old Akkadian period, when Naram-Sin frequently invokes the "warlike Ištar" (aštar annunītum) in his inscriptions (A. Westenholz 1999: 49) and becomes more prominent in the Neo-Assyrian veneration of Inana/Ištar, whose two most important aspects in this period, namely, Ištar of Nineveh and Ištar of Arbela, were intimately linked to the person of the king (Porter 2004: 42). The warrior aspect of Inana/Ištar, which does not appear before the Old Akkadian period (Selz 2000: 34), emphasizes her masculine characteristics, whereas her sexuality is feminine. Divine Genealogy and Syncretisms The family tree of Inana/Ištar differs according to different traditions. She is variously the daughter of Anu or the daughter of Nanna/Sin and his wife Ningal; and sister of Utu/Šamaš (Abusch 2000: 23); or else the daughter of Enki/Ea. Her sister is Ereškigal. Inana/Ištar does not have a permanent spouse per se, but has an ambivalent relationship with her lover Dumuzi/Tammuz whom she eventually condemns to death. She is also paired with the war god Zababa. In the Assyrian Empire, Ištar of Nineveh and Ištar of Arbela were treated as two distinct goddesses in royal inscriptions and treaties of Assurbanipal. Also during this period Ištar was made the spouse of Aššur and known by the alternative name of Mulliltu in this particular role (Porter 2004: 42). Cult Place(s) The main city of Inana/Ištar is Uruk. As one of the foremost Mesopotamian deities, she had temples in all important cities: Adab, Akkade, Babylon, Badtibira, Girsu, Isin, Kazallu, Kiš, Larsa, Nippur, Sippar, Šuruppak, Umma, Ur (Wilcke 1976-80: 78; see also George 1993 for a comprehensive list). Time Periods Attested Inana is listed in third place after An and Enlil in the Early Dynastic Fara god-lists (Litke 1998). Inana/Ištar remains in the upper crust of the Mesopotamian pantheon through the third, second and the first millennia. She is especially significant as a national Assyrian deity, particularly in the first millennium. Iconography The Iconography of Inana/Ištar is as varied as her characteristics. In early iconography she is represented by a reed bundle/gatepost Frankfort 1939: 15; Szarzyńska 2000: 71, Figs. 4-5), which is also the written form of her name in very early texts (Black and Green 1998: 108). The uppermost register of the famous Uruk Vase shows the goddess in anthropomorphic form, standing before two such gateposts (Black and Green 1998: 150, Fig.122). In human form as the goddess of sexual love, Inana/Ištar is often depicted fully nude. In Syrian iconography, she often reveals herself by holding open a cape. The nude female is an extremely common theme in ancient Near Eastern art, however, and although variously ascribed to the sphere of Inana/Ištar (as acolytes or cult statuettes), they probably do not all represent the goddess herself. A sound indication of divine status is the presence of the horned cap. In her warrior aspect, Inana/Ištar is shown dressed in a flounced robe with weapons coming out of her shoulder, often with at least one other weapon in her hand and sometimes with a beard, to emphasize her masculine side. Her attribute animal as the goddess of war is the lion, on the back of which she often has one foot or fully stands. In praise of her warlike qualities, she is compared to a roaring, fearsome lion (see Inana and Ebih, ETCSL 1.3.2). In her astral aspect, Inana/Ištar is symbolized by the eight-pointed star. The colours red and carnelian, and the cooler blue and lapis lazuli, were also used to symbolise the goddess, perhaps to highlight her female and male aspects respectively (Barret 2007: 27). Name and Spellings Inana/Inanna is the Sumerian name of this goddess. It is most often etymologically interpreted as nin.an.a(k), literally "Lady of the heavens" (Selz 2000: 29). A different interpretation (Jacobsen 1976: 36) translates her name as "Lady of the date clusters." The Semitic name Ištar originally belonged to an independent goddess that was later merged and identified with the Sumerian Inana (Abusch 2000: 23). The meaning of her name is also unclear (for more information see Westenholz 2000: 345). https://www.worldhistory.org/Inanna/ Inanna is the ancient Sumerian goddess of love, sensuality, fertility, procreation, and also of war. She later became identified by the Akkadians and Assyrians as the goddess Ishtar, and further with the Hittite Sauska, the Phoenician Astarte and the Greek Aphrodite, among many others. She was also seen as the bright star of the morning and evening, Venus, and identified with the Roman goddess. Inanna is one of the candidates cited as the subject of the Burney Relief (better known as The Queen of the Night), a terracotta relief dating from the reign of Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1792-1750 BCE) although her sister Ereshkigal is the goddess most likely depicted. In the famous Sumerian/Babylonian poem The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2700 - 1400 BCE) Inanna appears as Ishtar and, in Phoenician mythology, as Astarte. In the Greek myth The Judgment of Paris, but also in other tales of the ancient Greeks, the goddess Aphrodite is traditionally associated with Inanna through her great beauty and sensuality. Inanna is always depicted as a young woman, never as mother or faithful wife, who is fully aware of her feminine power and confronts life boldly without fear of how she will be perceived by others, especially by men. Aspects of the Goddess She is often shown in the company of a lion, denoting courage, and sometimes even riding the lion as a sign of her supremacy over the 'king of beasts'. In her aspect as goddess of war, Inanna is depicted in the armor of a male, in battle dress (statues frequently show her armed with a quiver and bow) and so is also identified with the Greek goddess Athena Nike. She has been further associated with the goddess Demeter as a fertility deity, and with Persephone as a dying-and-reviving god figure, no doubt a carry-over from her original incarnation as a rural goddess of agriculture. Although some writers have claimed otherwise, Inanna was never seen as a Mother Goddess in the way that other deities, such as Ninhursag, were. Dr. Jeremy Black notes: One aspect of [Inanna's personality] is that of a goddess of love and sexual behaviour, but especially connected with extra-marital sex and - in a way which has not been fully researched - with prostitution. Inanna is not a goddess of marriage, nor is she a mother goddess. The so-called Sacred Marriage in which she participates carries no overtones of moral implication for human marriages. (108). The Enduring Goddess Inanna is among the oldest deities whose names are recorded in ancient Sumer. She is listed among the earliest seven divine powers: Anu, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna. These seven would form the basis for many of the characteristics of the gods who followed. In the case of Inanna, as noted above, she would inspire similar deities in many other cultures. A vastly different personality from that of the traditional Mother Goddess (as exemplified in Ninhursag), Inanna is a brash, independant young woman; impulsive and yet calculating, kind and at the same time careless with other's feelings or property or even their lives. Jeremy Black writes: The fact that in no tradition does Inanna have a permanent male spouse is closely linked to her role as the goddess of sexual love. Even Dumuzi, who is often described as her `lover', has a very ambiguous relationship with her and she is ultimately responsible for his death. (108) Inanna endured, however, because she was so accessible and recognizable. Women and men both could relate to this goddess and it was no coincidence that both sexes served her as priests, temple servants, and sacred prostitutes. Inanna made people want to serve her because of who she was, not what she had to offer, and her devotees remained faithful to her long after worship in her temples had ceased. She was closely associated with the morning and evening star and, even the present day, she continues to be - even if few remember her name. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

Syncretism and Sacred Prostitution ,lol. the belief in the mother goddess and the goddess of sex is from Spain to the Arabian peninsula and Mesopotamia. The only thing that would have to be investigated would be rites, even the iconography is the same. There is quite a bit of modern Neonoaganism. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

I have found more than 16 symbols in just 10 files and there are even more in just one file. -

those yaketerina mods are very odd.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

B the iconography of all these goddesses is the same. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mother_goddess https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asherah https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inanna -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

https://www.ancient.eu/related/3-5285/44/ indeed not confirmed. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necrópolis_de_los_Rabs (Spanish only) https://www.worldhistory.org/Carthaginian_Religion/ -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

@Stan` Did anyone save this? -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

this would be the idea for now, to go looking for all the original drawing and converting it to vector file. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

Xiongnu Sundiata. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

I'm going to do some of these. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

this group was so good that I was even copied by modders from Total war center Forums. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

[Task] [Art Management] Gathering all symbology in vectorial art

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

@Stan` I was talking to @wowgetoffyourcellphone about this, I think it is important to keep it in one organized file. I will store them in a sorted grid with a description.