-

Posts

2.049 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

49

Posts posted by Genava55

-

-

-

1

1

-

-

59 minutes ago, wowgetoffyourcellphone said:

Lanciarius is first attested in 1st century BC iirc

1st century AD, by Flavius Joseph:

-

1

1

-

2

2

-

-

5 hours ago, Lion.Kanzen said:

I don't found anything.

antesignanus not antisignanus sorry.

Thats the singular of antesignanii

18 minutes ago, wowgetoffyourcellphone said:Currently in the patch we use Lanciarius to replace Veles.

Like you did with the Imperial Romans? Why not.

-

26 minutes ago, Lion.Kanzen said:

The problem is that with what we replace the troops, we have problems with the replacements of the Velites and Extraordinarii.

Evocatus is a good idea.

To replace the velite, you could use the antisignanus.

-

2

2

-

-

1 hour ago, Lion.Kanzen said:

Modern historians have also sometimes credited to Marius the abolition of Roman cavalry and light infantry and their replacement with auxilia. There is no direct evidence for this contention, which is driven largely by literary sources' silence on those branches after the 2nd century; continued inscriptional evidence attests both citizen cavalry and light infantry into the end of the republic.[53] The decline of Roman light infantry has been connected not to reform but cost. Because the logistical cost of supporting light infantry and heavy infantry was relatively similar, the Romans chose to deploy heavy infantry in extended and distant campaigns due to their greater combat effectiveness, especially when local levies could substitute for light infantry brought from Rome and Italy.

Yes, the Marian reforms are mostly a myth. The changes were gradual, Marius only contributed to a few modest things.

QuoteThe Reforms That Weren’t

We can then return to our list at the beginning:

- Cohorts: Experimented with before Marius, especially in Spain. Marius uses cohorts, but there’s no evidence he systematized or standardized this or was particularly new or unusual in doing so. Probably the actual breakpoint here is the Social War.

- Poor Volunteers Instead of Conscripted Assidui: Marius does not represent a break in the normal function of the Roman dilectus but a continuation of the Roman tradition of taking volunteers or dipping into the capite censi in a crisis. The traditional Roman conscription system functions for decades after Marius and a full professional army doesn’t emerge until Augustus.

- Discharge bonuses or land as a regular feature of Roman service: Once again, this isn’t Marius but Imperator Caesar Augustus who does this. Rewarding soldiers with loot and using conquered lands to form colonies wasn’t new and Marius doesn’t standardize it, Augustus does.

- No More equites and velites: No reason in the source to suppose Marius does this and plenty of reasons to suppose he doesn’t. Both velites and equites seem to continue at least a little bit into the first century. Fully replacing these roles with auxilia is once again a job for our man, Imperator Caesar Augustus, divi filius, pater patriae, reformer of armies, gestae of res, and all the rest.

- State-Supplied Equipment: No evidence in the sources. This shift is happening but is not associated with Marius. In any event, the conformity of imperial pay records with Polybius’ system of deductions for the second century BC suggests no major, clean break in the system.

- A New Sort of Pilum: No evidence, probably didn’t exist, made up by Plutarch or his sources. Roman pilum design is shifting, but not in the ways Plutarch suggests. If a Marian pilum did exist, the idea didn’t stick.

- Aquila Standards: Eagle standards pre-date Marius and non-eagle standards post-date him, but this may be one thing he actually does do, amplifying the importance of the eagle as the primary standard of the legion.

- The sarcina and furca and making Roman soldiers carry things: By no means new to Marius. This is a topos of Roman commanders before and after Marius. There is no reason to suppose he was unusual in this regard.

https://acoup.blog/2023/06/30/collections-the-marian-reforms-werent-a-thing/

+

QuoteMoving to the body of the text, Chapter 1 responds to Sallust’s statement (Iug. 86.2) that, in 107, Marius recruited volunteers from the capite censi; this has been central to most scholarly accounts of the first-century army. Cadiou is not the first to downplay the significance of these reforms, as he concedes, pointing especially to Rich.[2] In the first chapter, Cadiou reinforces these existing arguments against the Marian reform, presenting it rather in the context of Marius’s immediate need for haste. But if the “Marian reform” is no longer seen by specialists as the revolutionary act which ushered in the proletarian army, this does not seem to have diminished the scholarly consensus that a revolution took place. But that is precisely what Cadiou is arguing against.

https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2021/2021.06.02/

+

Quote"He admitted for the first time to his army capite censi, men who failed to meet the normal property qualification for service. The numbers were small but, in later periods of crisis, Marius's imitators recruited from this area on a grand scale. [...] His enrolment in the army of capite censi was imitated by later commanders in the civil wars, which destroyed the Republic" - Yann Le Bohec, The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, p.636

"The 2nd century BCE also saw the transition from the maniple to the cohort as the basic tactical unit. This change has often been attributed by modern scholars (Dobson 2008: 58) to Caius Marius, who is said to have introduced cohorts in order to counter the tactics of the Germans who were invading northern Italy toward the end of the 2nd century BCE. However, the sources, which do not explicitly refer to the change, suggest a change in the form of a long transitional process in which the Romans may have copied this formation from their allies (Livy 10.33.1 ; 23.17.11). The earliest reliable references to the Roman cohort date back to the Second Punic War (e.g., Livy 25.39.1 ; Polyb. 1 1.23.1-2), while maniples are last mentioned in field operation in the war against Jugurtha in 109 BCE (Sall. lug. 49.6). The fact that the sources frequently mention cohorts in war contexts in Spain also suggests that the change originated there and may have been due to a combination of factors peculiar to Spain." - Yann Le Bohec, The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, p.525.

Modern historians have often assumed that Gaius Marius introduced wide ranging and long - lasting reforms that greatly transformed the Roman army and had a profound impact on Roman politics as well. The so - called Marian reforms supposedly involved both tactical innovations and significant reorganization of military recruitment and financing. These included: the elimination of the Roman cavalry (to be replaced entirely by foreign auxiliary cavalry), the disbandment of light - armed troops and the standardization of the weapons and kit of heavy infantry, the reorganization of legions into cohorts (replacing the earlier, manipular structure), and perhaps most significantly, the recruitment of landless soldiers who previously would not have met minimum property qualifications. These new recruits would be mostly volunteers and receive grants of land upon release. Lastly, it is often assumed that these reforms were permanent. Thus, according to the communis opinio, Marius permanently transformed the Roman military into a professional army that was mostly composed of landless citizens equipped uniformly. Yet, despite the widespread acceptance of this view, there is actually very little evidence for the “Marian Reforms.” - François Gauthier, The Changing Composition of the Roman Army in the Late Republic and the So-Called Marian-Reforms.

"The old view that Marius gave Rome a professional army can no longer be maintained (Brunt 1971, 406–11; Rich 1983). His enrolment of men without the property qualification in 107 was in all probability an isolated episode: the hostility which it aroused makes it unlikely that his successors followed suit. The traditional procedures of the levy, including the property qualification, probably ceased to operate in the chaotic conditions of the eighties." - John Rich & Graham Shipley, War and Society in the Roman World, p.4.

So it is something mostly popular in the wargame culture and in general public books.

-

3

3

-

I want more simple, colorful strategy games like Rising Lords that people will actually play with me

By Jonathan Bolding

Not every strategy game has to be gloomy and impenetrable.

Rising Lords is just the sort of game I'm most vulnerable to: historical strategy with the simple setup of a tabletop wargame and the quality of life and large numbers that are only possible when a computer does the math and moves the pieces for you. What I especially like about it, though, is that it's colorful—which might be one reason I can actually get people to play it with me.

Despite what the movies say, the medieval world was not a drab palette of mud and polished steel. It was colorful and wild and flamboyant and made of rich fabrics and painted armors, and Rising Lords gets that. The rich earth and bright gem tones give off the effect of an actual medieval tapestry or fresco painting, with fantastic designs inspired by things like the Lewis chessmen.

Sadly, whatever blessing was given to the world was not given to the user interface, which is, while not without charm, either too sparse and lacking in explanation or cluttered with unimportant detail. As a strategy game fan, however, I am never stopped by an insufficient user interface. I am sometimes encouraged by it, perhaps to the detriment of myself and the genre, but it's worth bearing with it in the case of Rising Lords, which is just the kind of easily-to-digest strategy game I'd love to see more of.

[...] Full article below

-

1

1

-

-

-

17 hours ago, Thorfinn the Shallow Minded said:

Honestly, I have rarely seen a blog post written with such bad faith. In my opinion, the argumentation is of very low quality .

First of all, the anecdote of the 20'000 slaves fleeing Decelea is not really appropriate to speak about the condition of the Helots in comparison with the Athenian slaves. Nothing suggest those 20'000 slaves would become helots and nothing suggest those slaves choose to become helots. Most of the helots are actually local populations from Laconia and I don't think there is evidence of new helots imported from prisoners. So the 20'000 slaves would not have been made helots and they probably knew it. Furthermore, as a contradictory anecdote, slaves flew the city of Chios to join the Athenians who were besieging the city and they helped them (Thuc. 8.40.2). So really, this sort of anecdotes doesn't tell anything about the conditions of the slaves. Those are very specific situations and totally unrelated to the everyday life of the slaves.

H. P. Schrader also mentions that the Krypteia didn't exist during the Golden Age of Sparta, a claim that is dubious. Using Aristotle and Herodotus account's, Krypteia has probably an older origin. But anyway the whole argument of saying that the Krypteia didn't exist during the Golden Age of Sparta is simply dull, I don't see how it is used as a defense. This is Sparta but not the Golden Age Sparta so it doesn't count?

Finally H. P. Schrader mentioned that Athens committed a massacre of the population of Melos, as a sort counter-example to excuse the massacre of the 2000 helots who helped Sparta during the war and who thought they would receive freedom, but instead were slaughtered by their masters. Just this argument gave me a very bad opinion of this person, this is rhetorically the bottom-pit of intelligence. This is pure bad faith and a desperate argument. The situation at Melos has nothing to do with the slaves or with anything related to slavery. This is indeed a massacre but which happened at the heart of the war when Sparta already committed massacres too, notably killing all the Athenians prisoners after a battle etc. I don't think Sparta was worst than Athens on the respect of the enemies and of the prisoners (with the exception of the Messenians and the helots). But this whole argument has nothing to do with the slave conditions which is the topic of her article. H. P. Schrader is simply making a deflective argument, this is basically her saying "see, Athens was very bad too!" while giving an example related to a different topic.

In the end, a childish article.

-

1 hour ago, Thorfinn the Shallow Minded said:

Fair, yet I find the idea of him projecting trauma onto Spartans to be problematic.

1 hour ago, Thorfinn the Shallow Minded said:Hodkinson rightly notes that the skills of the crypteia would give would have little battlefield utility, and rather, it would seem to be a way of finding the best of what could make up the future Spartan leadership as they worked with minimal instruction, acting on their own initiative.

Devereaux's comparison is interesting because it makes parallels with the current goals of indoctrinating childs in such ways. The purpose is not their efficiency in the battlefield but to maintain an oppressive system. I don't see it as something implausible as such systems existed in other societies. Devereaux writing style is rendering his argument as something bold and exaggerated but it has some truth in my opinion.

-

1 hour ago, Thorfinn the Shallow Minded said:

That is a tricky question to really say, but I would argue that they were about at the same level of other servile classes like Athenian slaves.

Did you see the following quotes?

On 23/01/2024 at 10:00 PM, Genava55 said:You are confusing the Perioikoi and the Helots. The Perioikoi lived in cities and were free men. The Helots lived in the countryside, in villages.

If I can quote an excerpt from the book "Greek Slave Systems in their Eastern Mediterranean Context c.800-146 BC" to answer you, here it is:

<< What we might call ‘communal intervention’ went much further, however, than merely the occasional borrowing of a helot without the permission of his owner. The Old Oligarch, writing in the 420s, laments the inability of Athenian citizens to strike capriciously any slaves within their reach, a practice that he fondly notes is possible in Sparta ([Xen.] Ath. Pol. 1.10–12). This ability of non-owners to beat slaves is further attested by the Hellenistic historian Myron of Priene, known for his pro-Messenian and anti-Spartan attitudes. Myron writes that the Spartans forced the helots to wear degrading clothes, prescribed for them an annual whipping (to remind them they were slaves), and permitted magistrates to execute any helots whose physical size and vigour they thought inappropriate for a slave—fining the helot’s owner as well for letting him reach such girth (FGrHist 106 F2 ap. Athen. 14.74. 657c–d). This might sound sensational, but the rationale of such measures— that is, targeting large, powerful helots who might be potential rebel leaders—is observable in fifth- and fourth-century sources as well. Aristotle’s description of the krypteia is perhaps the best example of this. According to his account, from time to time youths would be sent into the countryside armed with daggers and carrying only the most meagre rations. They would hide during the day, emerging at night to kill any helots whom they found abroad on the roads (surely some manner of curfew is implied). They would also infiltrate the fields and dispatch those who were particularly large or vigorous (Arist. fr. 538 [Rose] ap. Plu. Lyc. 28. 1–4; cf. Arist. fr. 611.10 [Rose] ap. Herakleides fr. 10 [Dilts]). Aristotle further noted (ap. Plu. Lyc. 28.4) that the ephors declared war on the helots each year, thus absolving those Spartiates (surely for the most part the krypteia) who murdered helots from miasma, effectively granting them a ‘licence to kill’. All of these sources tally with the remark of Critias (in the epigraph to this chapter) that at Sparta were to be found the most enslaved and the most free of men, which must refer to helots and Spartiates: helots—of all Greek slaves—were subject to the most oppressive and unusual means of control; Spartiates—of all free Greeks—were those most liberated from the need to perform manual labour.

Let us sum up so far. The picture painted by our contemporary sources is that individual Spartans were able to own helots, and this included the power to sell them, though not outside Spartan territory; they could not manumit them in any way whatsoever. Furthermore, their helots could be commandeered by their fellow citizens for minor tasks, and could be disciplined by them as well. Most remarkably, the state could manumit or even kill these apparently privately owned slaves. It is now necessary both to explain why these rules existed and then to determine whether or not such measures of communal intervention push helotage outside our classificatory scheme of private ownership. >>

Another one:

<< The most famous act of state brutality of this ilk is the alleged massacre of 2,000 helots narrated by Thucydides (4.80), who says that a proclamation was made to the helots inviting those who thought they had served the state well in war to come forward and receive their freedom. Those who answered the summons processed around the temples, but then promptly disappeared; nobody knew how each individual died. >>

-

10 minutes ago, ShadowOfHassen said:

They do say that, and for the most I'd agree. Secret police, slavery and the agoge are things almost no sane person would do today. However, the articles seemed to make the argument that because of those things the story of the 300 should not be held up as an example of bravery and sacrifice that should be emulated (as it has been up as since the day it happened)

The article starts like this:

Many self-professed champions of freedom throughout the centuries have looked to ancient Sparta as an inspiration. The doomed stand of 300 Spartan warriors against the Persian Empire at Thermopylae in 480 B.C.E.—the subject of Zack Snyder’s 2006 film 300—has been particularly influential for figures ranging from Lord Byron rallying support for Greek independence from the Ottomans to Cold Warriors mythologizing the virtues of the “West” against the Soviet Union. It’s easy to ridicule such a simplistic view of history, and to point out that the Spartans might not have deserved their reputation as invincible warriors. But the blunders and brutalities of today’s champions of “Western civilization” follow Sparta’s example remarkably closely. This should give us pause.

So it is not the last stand of the 300 but the idealization of Spartans and of the city-state Sparta that is criticized.

-

18 hours ago, ShadowOfHassen said:

For example: Yes, Sparta did rely on the Helots for manual labor. However, it was technically less like slavery and more like oppressed serfdom -- not to say that Sparta didn't own slaves, but the Helot population as a whole weren't slaves. The Helots were more like a really low class. If my memory serves me right, when I researched Sparta I read that the Helots had their own towns, and some translated inscriptions from the area that seemed to suggest that helots weren't constrained to the Spartan's minimalist lifestyle, and sometimes lived more lavishly than their "oppressors"

18 hours ago, ShadowOfHassen said:Also, I have not found a single piece of evidence that Sparta treated the people they conquered worse than any other civilization did.

You are confusing the Perioikoi and the Helots. The Perioikoi lived in cities and were free men. The Helots lived in the countryside, in villages.

If I can quote an excerpt from the book "Greek Slave Systems in their Eastern Mediterranean Context c.800-146 BC" to answer you, here it is:

<< What we might call ‘communal intervention’ went much further, however, than merely the occasional borrowing of a helot without the permission of his owner. The Old Oligarch, writing in the 420s, laments the inability of Athenian citizens to strike capriciously any slaves within their reach, a practice that he fondly notes is possible in Sparta ([Xen.] Ath. Pol. 1.10–12). This ability of non-owners to beat slaves is further attested by the Hellenistic historian Myron of Priene, known for his pro-Messenian and anti-Spartan attitudes. Myron writes that the Spartans forced the helots to wear degrading clothes, prescribed for them an annual whipping (to remind them they were slaves), and permitted magistrates to execute any helots whose physical size and vigour they thought inappropriate for a slave—fining the helot’s owner as well for letting him reach such girth (FGrHist 106 F2 ap. Athen. 14.74. 657c–d). This might sound sensational, but the rationale of such measures— that is, targeting large, powerful helots who might be potential rebel leaders—is observable in fifth- and fourth-century sources as well. Aristotle’s description of the krypteia is perhaps the best example of this. According to his account, from time to time youths would be sent into the countryside armed with daggers and carrying only the most meagre rations. They would hide during the day, emerging at night to kill any helots whom they found abroad on the roads (surely some manner of curfew is implied). They would also infiltrate the fields and dispatch those who were particularly large or vigorous (Arist. fr. 538 [Rose] ap. Plu. Lyc. 28. 1–4; cf. Arist. fr. 611.10 [Rose] ap. Herakleides fr. 10 [Dilts]). Aristotle further noted (ap. Plu. Lyc. 28.4) that the ephors declared war on the helots each year, thus absolving those Spartiates (surely for the most part the krypteia) who murdered helots from miasma, effectively granting them a ‘licence to kill’. All of these sources tally with the remark of Critias (in the epigraph to this chapter) that at Sparta were to be found the most enslaved and the most free of men, which must refer to helots and Spartiates: helots—of all Greek slaves—were subject to the most oppressive and unusual means of control; Spartiates—of all free Greeks—were those most liberated from the need to perform manual labour.

Let us sum up so far. The picture painted by our contemporary sources is that individual Spartans were able to own helots, and this included the power to sell them, though not outside Spartan territory; they could not manumit them in any way whatsoever. Furthermore, their helots could be commandeered by their fellow citizens for minor tasks, and could be disciplined by them as well. Most remarkably, the state could manumit or even kill these apparently privately owned slaves. It is now necessary both to explain why these rules existed and then to determine whether or not such measures of communal intervention push helotage outside our classificatory scheme of private ownership. >>

Another one:

<< The most famous act of state brutality of this ilk is the alleged massacre of 2,000 helots narrated by Thucydides (4.80), who says that a proclamation was made to the helots inviting those who thought they had served the state well in war to come forward and receive their freedom. Those who answered the summons processed around the temples, but then promptly disappeared; nobody knew how each individual died. >>

-

1 hour ago, ShadowOfHassen said:

While both of those articles are pushing against a romanticized version of Sparta, something that is to be applauded. I wouldn't recommend taking what they say as the gospel truth. According to my research, Sparta was probably somewhere between the two extremes.

Which claim do you find too extreme? When they say Sparta relying heavily on slavery?

-

1

1

-

-

4 hours ago, wowgetoffyourcellphone said:

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2024/01/sparta-300-warriors-history-slavery.html

A good write up addressing the modern obsession with Sparta.

-

Interesting. How do you work together on this project? Do you have an internal section on the forum or do you use other means like discord? Or you are only submitting changes through github or others?

-

Interesting article about Age of Empire original technology, based on Assembly:

This isn't quite on those lines, but a redditor recently noted that Chris Sawyer wrote Rollercoaster Tycoon 1 and 2 in Assembly language, and apparently Age of Empires was the same: "AoE is written in Assembly: is this actually TRUE?!" It's important to note that this wasn't uncommon back in the day, though it would still be pretty remarkable if an entire game was hard-coded this way. Assembly language, to be as brief as possible, is any low-level coding language that communicates more directly with a computer's architecture than high-level languages like C++.

The question about whether Age of Empires was coded in Assembly language hit gold in the replies thanks to Matt Pritchard, one of the founding members of Ensemble Studios, who was in charge of graphics and optimisation on the early games, and on the later HD / DE editions the coding lead.

"I guess I can clarify this, since I wrote all the assembly code used in Age of Empires and Age of Kings, along with many other parts of those games," says Pritchard. "There were about ~13,000 lines of x86 32-bit assembly code written in total."

[...]

The Assembly code remained in use even by the time of Age of Kings: HD edition (a 32-bit game), but Pritchard "re-wrote the assembly functions into C++ for both Definitive Editions, as they are 64-bit programs and inline assembly was never supported by the 64-bit C++ compiler, and the vastly improved register sets and compiler optimizations made it unnecessary. Additionally, sprite drawing in the definitive editions is multi-threaded, and will use up to 4 cores for that task alone."

-

1

1

-

-

Interesting video about the current issues with Total War games and the players community reaction to it

-

1

1

-

-

13 minutes ago, Bazaar said:

@Gurken Khan isn't it a first April joke one day later ? @user1?

There are 11 pages in this thread... so obviously no.

-

-

-

The Silk Road should not be a technology, it is better as a team bonus. Instead, give them a technology about producing paper maps and give them a speed bonus for the merchants.

-

3

3

-

-

<< S. K. Chowdhury’s analysis (Gaur, 1983) of the plant remains found in the Atranjikhera excavations reveals some important details. The OCP and BRW phases yielded a few remains of rice, barley, gram, and khesari. The PGW (Painted Grey Ware ~1100-800 BC) level gave evidence of wheat, and the manner in which plant remains were scattered about and found in heaps suggested more abundant grain production than before. The NBPW (Northern Black Polished Ware ~600-200 BC) phase showed the cultivation of rice, wheat, and barley, with the addition of a new pulse (Phaseolus mungo). The wood remains included laurel, farash, bamboo, deodar, and Himalayan cypress. As cedar and Himalayan cypress grow in the northern mountains, these finds suggest contact with these regions. Almost a thousand pieces of bone fragments from the site were analysed. Those belonging to the NBPW phase included bones of domesticated humped cattle, buffalo, goat, sheep, pig, and dog. Horse remains occurred in the PGW and post-PGW phases. Many animal bones were split or cut with sharp tools and charred—clear evidence that the animals were killed for food. The bones of cattle vastly outnumbered those of other animals, indicating that beef was an important part of the diet, apart from venison, mutton, and pork. >>

- A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p. 278

<< Excavations in the Parashurameshwara temple at Gudimallam (Chittoor district, AP) have revealed the history of this Shiva temple from the 2nd century BCE onwards (Sarma, 1994). In the earliest stage, the stone Shiva linga carved with the image of the god was placed within a 1.25 m square stone railing. The temple was hypaethral (open-air, roofless). Bones of domesticated sheep with cut marks on them suggest animal sacrifice. Phase II in the structural history of the temple is dated from the 1st to the 3rd centuries CE. An apsidal temple was built around the Shiva linga in this period. Considerable architectural elaboration took place in early medieval times. However, it is interesting to note that the same Shiva linga remained the object of worship in the sanctum throughout. >>

- A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p. 447

-

8 hours ago, Sandeep said:

Because Maurayans are the followers of vedic religion and do not eat cow, Bull or we can say red meat, its is forbidden,

The original Vedic religion didn't forbid the consumption of cow and beef meat. It is Brahmanism which started to incorporate new elements, notably forbidding the consumption of cow. See the following: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animal_sacrifice_in_Hinduism

The Brahmanic texts explicitly state that five creatures were suitable for sacrifice in Vedic India, in descending order man, horse, cattle, sheep, and goat. The texts of rigveda and other vedas provide detailed description of sacrifices including cattle sacrifice

Although it is true that it started progressively during the Mauryan period. Ahsoka notably promoted a vegetarian life.

-

1

1

-

-

Liburnian ships

-

1

1

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

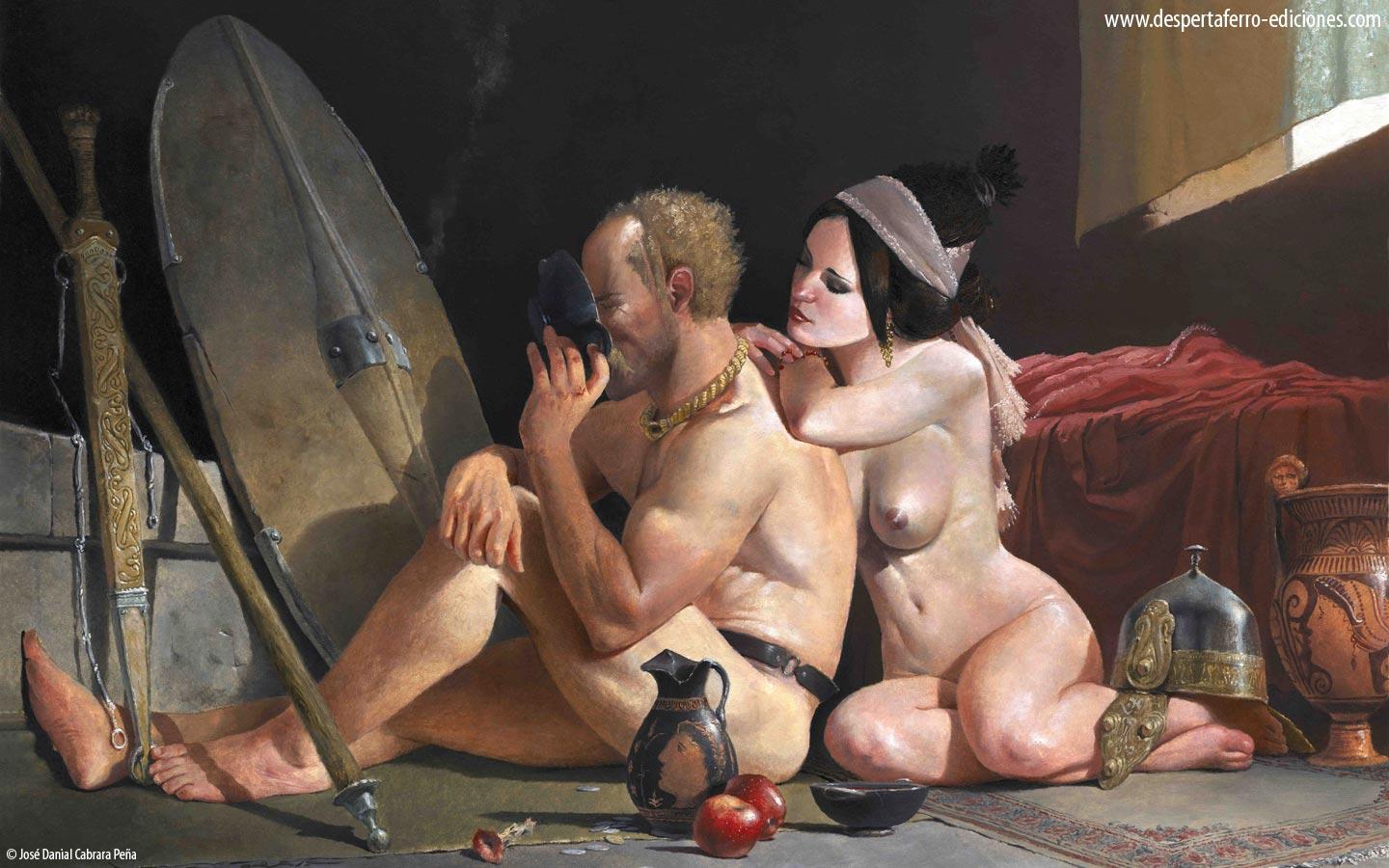

Marian Reforms (Romans) General Discussion.

in Gameplay Discussion

Posted

Antesignani means "those before the standard" or "those in front of the standard". Don't try to think to much about them, this is really a can of worms. It is not even certain if the Antesignani were a specialized troop or simply a label describing any men fighting in particular circonstances.