-

Posts

2.067 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

52

Posts posted by Genava55

-

-

17 minutes ago, Nescio said:

Well, we know onagers were invented by the Romans during the 4th C AD

Actually we don't know the Romans invented it, but the earliest account is in Ammianus Marcellinus book. The account itself makes me think it is an older weapon because of the confusion between the names and the author noting that the reference to an onager comes from "modern times", in opposition to an other name.

17 minutes ago, Nescio said:Now I don't know what to make of that cart-wheel, might it have been horizontal?

It could be, but how it would make it look like a "cart-wheel shape"? Personally I preferred a vertical design because it is more striking visually.

17 minutes ago, Nescio said:The easiest solution would probably be to give the Mauryas a Greek-style (i.e. Macedonian) torsion engine. I'm not saying they had, just that's not inconceivable.

Well, we have no indication they borrowed their siege engines from the Greeks. This is simply the most conservative and orthodox hypothesis. But if Jaina literature is correct, then a kind of catapult existed before the Mauryas (which is possible since the Chineses had one before the Han dynasty).

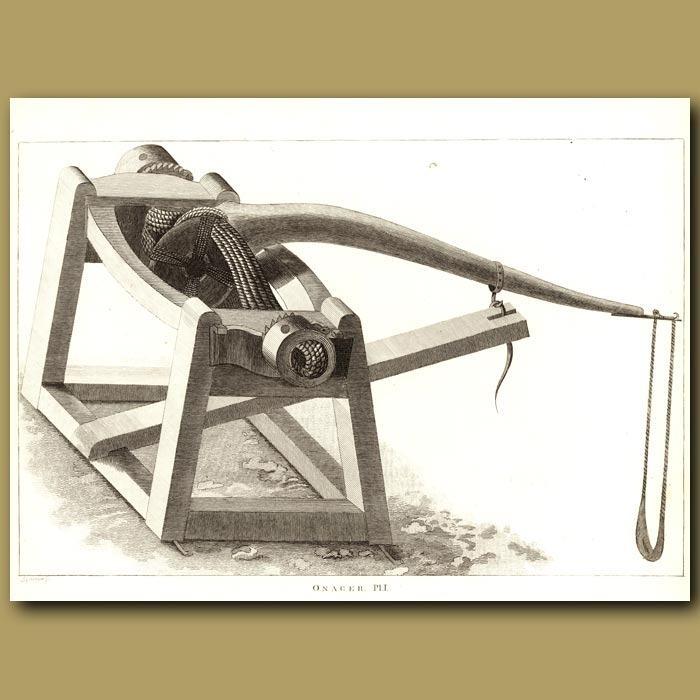

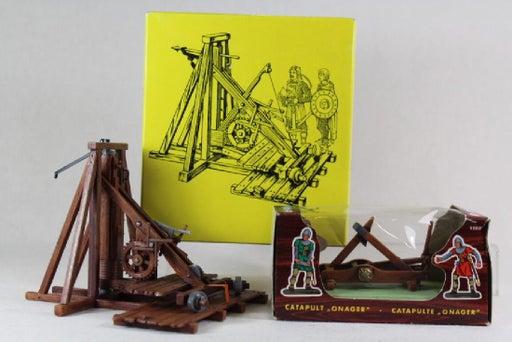

13 minutes ago, Stan` said:Fun fact. we have an onager...

This one?

-

1

1

-

-

7 minutes ago, Nescio said:

It's not entirely impossible they just might have existed. We just lack sources, descriptions, dimensions, drawings, etc., which would probably make it quite challenging for artists to model and animate one, but if someone wants to give it a try, I won't stop you.

Personally I am in favor of a catapult for the Mauryas, I find it a reasonable hypothesis according to the hints from literature.

We won't be able to reenact the original design, that's sure. But with reasonable supposition, it shouldn't be hard to have a working engine.

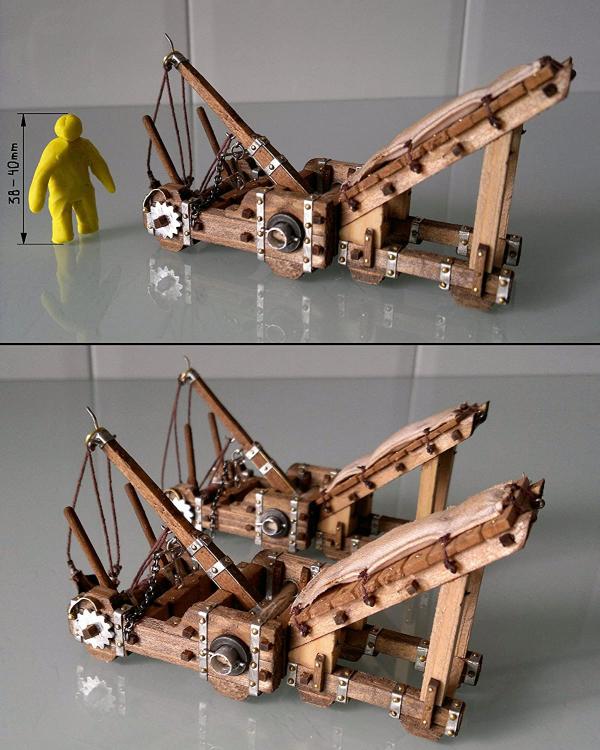

For example, an onager is not that hard to animate and to understand in its principle. The design should only be modified but its principle could stay the same.

-

@fatherbushido @Nescio @LordGood @Sundiata and anyone else wanting to give his/her opinion.

What about some stone-throwing catapults? Personally I think the cart-wheel shaped engine could be some kind of onager with two wheels twisted to make the torsion (like a ship's wheel to handle it).

Some ideas of devices that could fit large wheels:

Spoiler

Finally about the battering ram, I find interesting there is no mention of it.

What about a hammer-like device instead? It would fit the same role.

-

1

1

-

-

On 8/3/2020 at 11:42 PM, Carltonus said:

- Thracian Peltast - Thracian mercenary javelineer

- + Rhomphaiaphoros - Thracian mercenary swordsman (not champion as the deprecating Stoa, but like the Seleucid counterpart, replaces Black Cloak)

Why not Italic mercenaries?

I think we could take reference on the Lucanians to design new units.

-

From: A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Page 272.

Available on lib gen.

About Jaina literature:

I think I have found the source:

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

Having determined on this device and having put the god in his heart, the king, Śreṇika’s son, observed a three-day fast. Impelled by his penance and the friendship in a former birth, Śakra and Indra Camara came to him then. The Indra of the gods and the Indra of the Asuras said, “Sir, what do you wish?” He said, “If you are pleased, let Ceṭaka be killed.” Śakra said again: “Ask for something else. Ceṭaka is a co-religionist of mine, Certainly, I will not kill him. Nevertheless, king, I shall give you bodily protection, so that you will not be conquered by him.” He said, “Very well.” Indra Camara thought fit to make a battle which had big stones and a thorn,[2] and a second which had a chariot and a mace, leading to victory. In the first a pebble that had fallen would resemble a large stone. The thorn would be superior to a large weapon. In the second the chariot and the mace roam without an operator. The enemy-army, which had risen for battle, is crushed on all sides by them. Then the three, the Indra of the gods, the Indra of the Asuras, and the Indra of men, Kūṇika, fought with Ceṭaka’s army. A general, named Varuṇa, a grandson of the charioteer Nāga, an observer of the twelve vows, possessing right-belief, making a two-day fast, his mind always disgusted with worldly existence, having made a three-day fast at the end of the two-day fast, because of the attack on the king, strongly urged by King Ceṭaka himself, entered the battle, faithful to a promise, the chariot-mace being so irresistible.

https://www.wisdomlib.org/jainism/book/trishashti-shalaka-purusha-caritra/d/doc216048.html

This encyclopedia considers the same interpretation:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe133

I don't know if other Jaina texts gives the same account but with a less religious narrative.

-

1

1

-

-

So according to the Arthaśāstra (which is slightly out of our time frame), there are siege engines shooting projectiles at long distance:

- (Stationary) Sarvatobhadra is a cartwheel-shaped device that, when spun, hurls stones.

- (Stationary) Jāmadagnya is a device for shooting arrows.

- (Stationary and possibly) Bahumukha appears to refer to a position or a device on a tower from which arrows are shot.

- (Mobile) Āsphāṭima is a sort of catapult to hurl weapons.

Incendiary and anti-incendiary siege engines:

- (Stationary) Saṃghāṭī is a machine for propelling incendiary devices to burn down turrets.

- (Stationary) Parjanyaka is a kind of fire engine to put out fires.

A device to tear down pillars:

- (Mobile) Utpāṭima is a device for tearing down pillars.

Pillars and beams based defense:

- (Stationary) Viśvāsaghātin consists of a beam placed outside the city walls that, when released, kills approaching soldiers.

- (Stationary) Bāhu consists of two pillars meant, when released, to crush those coming between them.

- (Stationary) Ūrdhvabāhu is a similar device, but it consists of only one pillar 50 Hastas long, and Ardhabāhu is a pillar half as high.

- (Mobile) Devadaṇḍa is a long pole to be released from the top of the defensive wall.

Weapons hurled down to the enemy:

- (Stationary?) Yānaka is a rod one Daṇḍa long mounted on wheels and meant to be hurled at oncoming soldiers.

- (Mobile) Śataghni is a large pillar studded with sharp nails with a cartwheel at one end and intended to be hurled down at the enemies.

Mobile light weapons for siege:

- Musalayaṣṭi is a pike made of hard Accacia wood.

- Hastivāraka is a pole with two or three prongs to ward off elephants.

- Spr̥ktalā is a club with sharp points.

- Kuddála, a kind of spade.

- Udghāṭima is a hammer-type device.

- Mudgara and Gada, hammer and mace discharged by a mechanical device.

Other engines and devices:

- (Mobile) Tālavr̥nta is a fan-like device to hurl up dust against the enemy.

- (Mobile) Sūkarikā is a bag filled with cotton or wool to protect against stones hurled at the fortifications.

- (Mobile) Pāñcālika is a large wooden plank studded with sharp nails to be placed under the water in the moat.

-

2

2

-

1

1

-

During the Theban–Spartan War of 378–362 BC:

Diodorus Siculus, 15, 70, 1: From Sicily, Celts and Iberians to the number of two thousand sailed to Corinth, for they had been sent by the tyrant Dionysius to fight in alliance with the Lacedaemonians, and had received pay for five months. The Greeks, in order to make trial of them, led them forth; and they proved their worth in hand-to-hand fighting and in battles and many both of the Boeotians and of their allies were slain by them. Accordingly, having won repute for superior dexterity and courage and rendered many kinds of service, they were given awards by the Lacedaemonians and sent back home at the close of the summer to Sicily.

Xen. Hell. 7.1.20: Just after these events had happened, the expedition sent by Dionysius to aid the Lacedaemonians sailed in, numbering more than twenty triremes. And they brought Celts, Iberians, and about fifty horsemen. On the following day the Thebans and the rest, their allies, after forming themselves in detached bodies and filling the plain as far as the sea and as far as the hills adjoining the city, destroyed whatever of value there was in the plain. And the horsemen of the Athenians and of the Corinthians did not approach very near their army, seeing that the enemy were strong and numerous.

During the Peloponnesian war, about the Sicilian Expedition in 415-413 BC:

Thuc. 6.90: "Thus stands the matter touching my own accusation. And concerning what we are to consult of, both you and I, if I know anything which you yourselves do not, hear it now. [2] We made this voyage into Sicily, first (if we could) to subdue the Sicilians, after them the Italians, after them, to assay the dominion of Carthage, and Carthage itself. [3] If these or most of these enterprises succeeded, then next we should have undertaken Peloponnesus, with the accession both of the Greek forces there and with many mercenary barbarians, Iberians and others of those parts, confessed to be the most warlike of the barbarians that are now. we should also have built many galleys besides these which we have already (there being plenty of timber in Italy); with the which besieging Peloponnesus round, and also taking the cities thereof with our land forces, upon such occasions as should arise from the land, some by assault and some by siege, we hoped easily to have debelled it and afterwards to have gotten the dominion of all Greece. [4] As for money and corn to facilitate some points of this, the places we should have conquered there, besides what here we should have found, would sufficiently have furnished us.

Also Italian mercenaries on the side of Athenes against Sicily:

Thuc. 7.33: About the same time came unto them also the aid of the Camarinaeans, five hundred men of arms, three hundred darters, and three hundred archers. Also the Geloans sent them men for five galleys, besides four hundred darters and two hundred horsemen. [2] For now all Sicily, except the Agrigentines, who were neutral, but all the rest, who before stood looking on, came in to the Syracusian side against the Athenians. [3] [Nevertheless], the Syracusians, after this blow received amongst the Siculi, held their hands and assaulted not the Athenians for a while. Demosthenes and Eurymedon, having their army now ready, crossed over from Corcyra and the continent with the whole army to the promontory of Iapygia. From thence they went to the Choerades, islands of Iapygia, and here took in certain Iapygian darters to the number of two hundred and fifty, of the Messapian nation. [4] And having renewed a certain ancient alliance with Artas, who reigned there and granted them those darters, they went thence to Metapontum, a city of Italy. There, by virtue of a league, they got two galleys and three hundred darters, which taken aboard, they kept along the shore till they came to the territory of Thurii. [5] Here they found the adverse faction to the Athenians to have been lately driven out in a sedition. [6] And because they desired to muster their army here, that they might see if any were left behind, and persuade the Thurians to join with them freely in the war, and, as things stood, to have for friends and enemies the same that were so to the Athenians; they stayed about that in the territory of the Thurians.

-

2

2

-

-

To continue the debate:

And another important contribution from Nescio:

So there are evidences for a large variety of siege engines one or two centuries after the Mauryas. It is not perfectly on the good time frame and possibly some exchange and development have been in place after the Mauryas but they could be a heritage from the Mauryas as well.

What we do with this information?

Nescio, you beat me for a few seconds ahaha

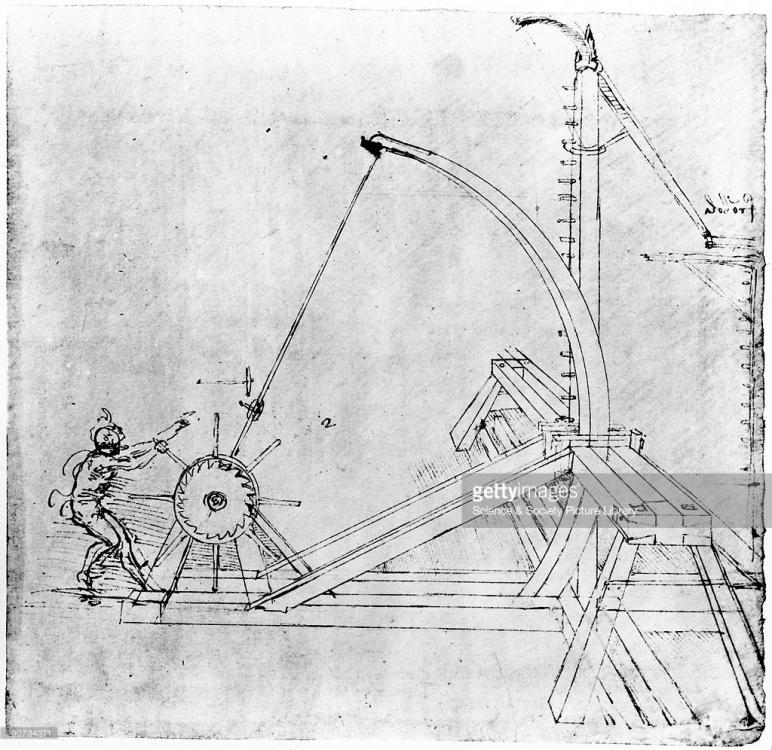

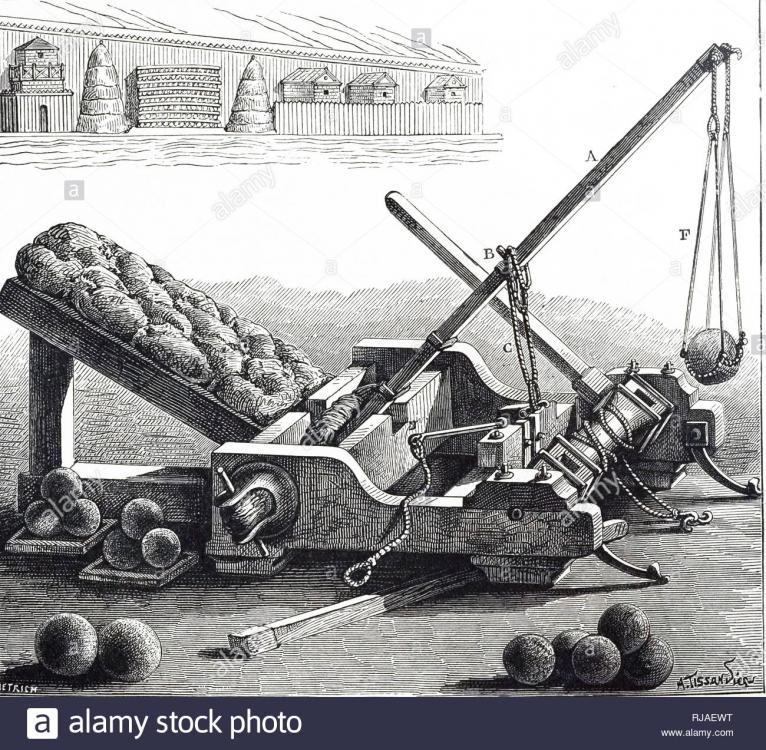

Edit: furthermore the weird "cartwheel-shaped" ballista/catapult is not really a description matching Roman or Greek examples at my knowledge. It seems to be a torsion engine using some kind of wheel or wheelS, to hurl stones.

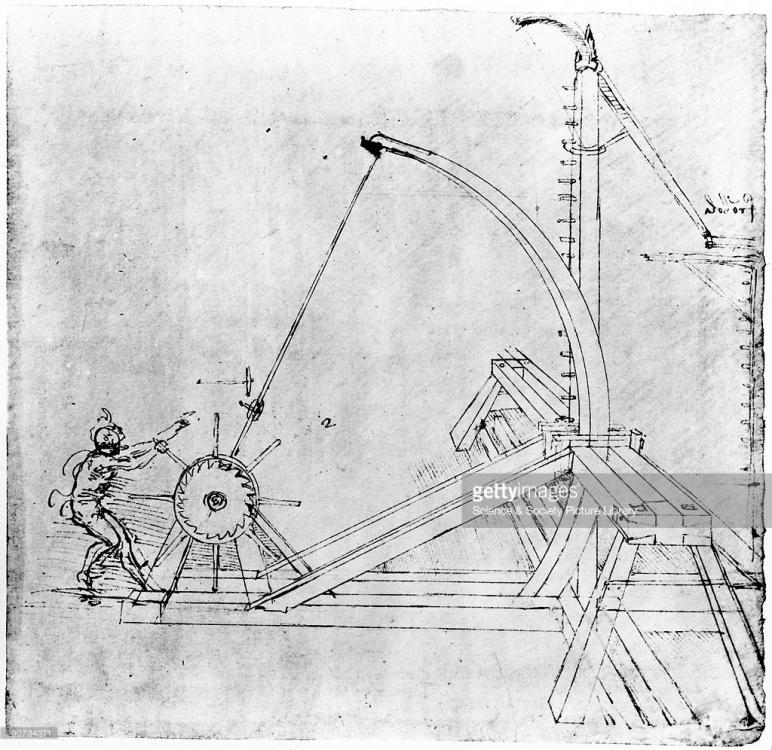

Edit2: some kind of springald catapult?

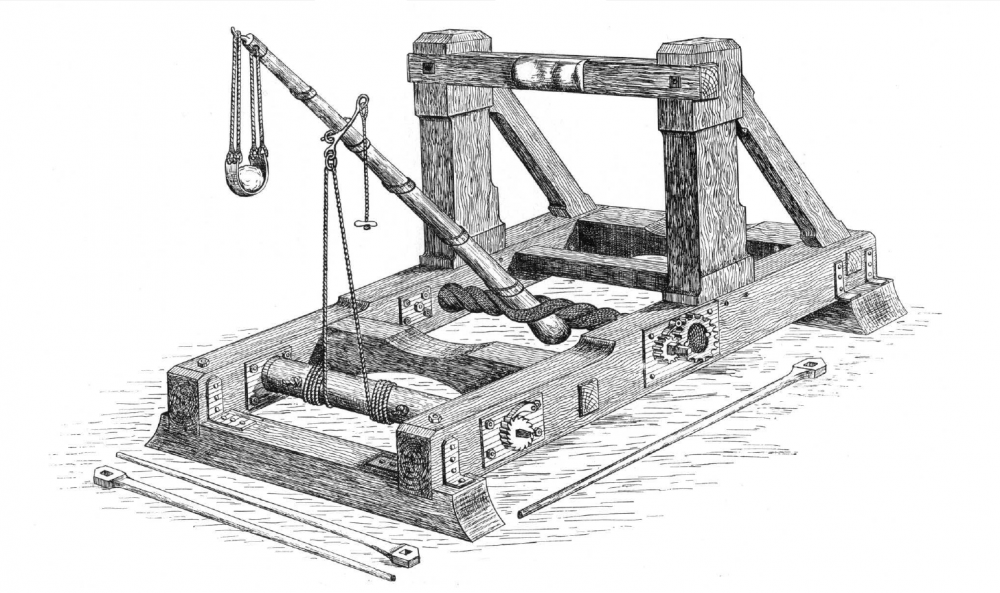

Edit3: or something like this trebuchet/mangonel? lol

Spoiler

g

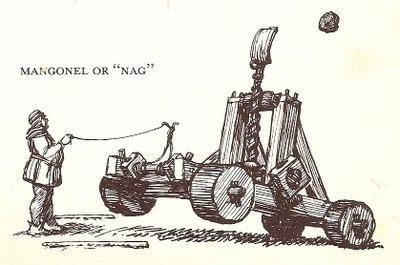

Edit 4: Or something much simpler (and much more credible):

Spoiler

-

1

1

-

-

16 minutes ago, myou5e said:

The number of naive matchups between civilizations is Sumi(n-1)i, where n=number of civilizations.

- with 3 civs, 2 + 1 = 3 matchups

- with 4 civs, 3 + 2 + 1 = 6 matchups

- with 5 civs, 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10 matchups

- with 13 civs(v24) = 78 Matchups

However If you match up similar factions internally, then test only that "general faction" against the others. You will reduce this number significantly.

- Celts(brit, gaul): 2 Matchups

- Greeks(athen, mace, spart): 3 Matchups

- Successor(sele + ptol): 1 Matchups

- I'm not sure if we can group the following, so we may need to treat them separately: Carthaginian, Iberian, Kushites, Mauryans, Romans, Persians

Because we can group some civs together, we have reduced the number of global matchups considerably. 6 Independent Civs, Plus 3 general cultures. That means 9 global matchups. 9 Global matchups results in 36 possible combinations, then we add the internal culture matchups, 36+2+3+1=42.

So practically speaking we only need to worry about 42 possible matchups, not 72. If we can categorize two of the independent civs i mentioned together, there will only be 8 global matchups, and total will reduce to 34.That's a very different approach than the original proposal in this thread but it could be a good idea in theory.

First we group the civs by strategical themes which gives 6 or 7 groups, then we balance the civs within the groups and finally the groups between them.

However, how do you balance groups between them (not within)? Simply by a statistical analysis of the matches online and with back-and-forth changes?

-

From the text quoted before:

QuoteSarvatobhadra, jamadagnya, bahumukha, visvásagháti, samgháti, yánaka, parjanyaka, ardhabáhu, and úrdhvabáhu are immoveable machines (sthirayantrám).

Pánchálika, devadanda, súkarika, musala, yashti, hastiváraka, tálavrinta, mudgara, gada, spriktala, kuddála, ásphátima, audhghátima, sataghni, trisúla, and chakra are moveable machines.

Translation from the book: King, Governance and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra. 2013.

Quote5. The stationary mechanical devices are Sarvatobhadra, Jāmadagnya, Bahumukha, Viśvāsaghātin, Saṃghāṭī, Yānaka, Parjanyaka, Bāhu, Ūrdhvabāhu, and Ardhabāhu.* 6. The mobile mechanical devices are Pāñcālika, Devadaṇḍa, Sūkarikā, Musalayaṣṭi, Hastivāraka, Tālavr̥nta, hammer, mace, Spr̥ktalā, spade, Āsphāṭima, Utpāṭima, Udghāṭima, Śataghni, trident, and discus.

Endnotes from King, Governance and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra:

QuoteSarvatobhadra... Ardhabāhu: The names of various weapons given in this chapter, coming no doubt from a specialized military vocabulary, are hard to identify. The meanings according to the commentators are as follows: Sarvatobhadra is a cartwheel-shaped device that, when spun, hurls stones. Jāmadagnya is a device for shooting arrows. Bahumukha appears to refer to a position or a device on a tower from which arrows are shot. Viśvāsaghātin consists of a beam placed outside the city walls that, when released, kills approaching soldiers. Saṃghāṭī is a machine for propelling incendiary devices to burn down turrets. Yānaka is a rod one Daṇḍa long mounted on wheels and meant to be hurled at oncoming soldiers. Parjanyaka is a kind of fire engine to put out fires. Bāhu consists of two pillars meant, when released, to crush those coming between them. Ūrdhvabāhu is a similar device, but it consists of only one pillar 50 Hastas long, and Ardhabāhu is a pillar half as high.

Pāñcālika is a large wooden plank studded with sharp nails to be placed under the water in the moat. Devadaṇḍa is a long pole to be released from the top of the defensive wall. Sūkarikā is a bag filled with cotton or wool to protect against stones hurled at the fortifications. Musalayaṣṭi is a pike made of hard Accacia wood. Hastivāraka is a pole with two or three prongs to ward off elephants. Tālavr̥nta is a fan-like device to hurl up dust against the enemy. Hammer and mace are weapons discharged by a mechanical device. Spr̥ktalā is a club with sharp points. The function of a spade is left unexplained. Āsphāṭima is a sort of catapult to hurl weapons. Utpāṭima is a device for tearing down pillars. Udghāṭima is a hammer-type device. Śataghni is a large pillar studded with sharp nails with a cartwheel at one end and intended to be hurled down at the enemies.

-

1

1

-

-

I re-open this topic to share a very useful reference:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Arthashastra

The Arthaśāstra is an ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is traditionally credited as the author of the text. The latter was a scholar at Takshashila, the teacher and guardian of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. Some scholars believe them to be the same person, while most have questioned this identification. The text is likely to be the work of several authors over centuries. Composed, expanded and redacted between the 2nd century BCE and 3rd century CE, the Arthashastra was influential until the 12th century, when it disappeared. It was rediscovered in 1905 by R. Shamasastry, who published it in 1909. The first English translation was published in 1915.

Here various excerpt from different chapters and books:

QuoteCHAPTER II. DIVISION OF LAND.

THE King shall make provision for pasture grounds on uncultivable tracts.

Bráhmans shall be provided with forests for sóma plantation, for religious learning, and for the performance of penance, such forests being rendered safe from the dangers from animate or inanimate objects, and being named after the tribal name (gótra) of the Bráhmans resident therein.

A forest as extensive as the above, provided with only one entrance rendered inaccessible by the construction of ditches all round, with plantations of delicious fruit trees, bushes, bowers, and thornless trees, with an expansive lake of water full of harmless animals, and with tigers (vyála), beasts of prey (márgáyuka), male and female elephants, young elephants, and bisons—all deprived of their claws and teeth—shall be formed for the king's sports.

On the extreme limit of the country or in any other suitable locality, another game-forest with game-beasts; open to all, shall also be made. In view of procuring all kinds of forest-produce described elsewhere, one or several forests shall be specially reserved.

Manufactories to prepare commodities from forest produce shall also be set up.

Wild tracts shall be separated from timber-forests. In the extreme limit of the country, elephant forests, separated from wild tracts, shall be formed.

The superintendent of forests with his retinue of forest guards shall not only maintain the up-keep of the forests, but also acquaint himself with all passages for entrance into, or exit from such of them as are mountainous or boggy or contain rivers or lakes.

Whoever kills an elephant shall be put to death.

Whoever brings in the pair of tusks of an elephant, dead from natural causes, shall receive a reward of four-and-a-half panas.

Guards of elephant forests, assisted by those who rear elephants, those who enchain the legs of elephants, those who guard the boundaries, those who live in forests, as well as by those who nurse elephants, shall, with the help of five or seven female elephants to help in tethering wild ones, trace the whereabouts of herds of elephants by following the course of urine and dungs left by elephants and along forest-tracts covered over with branches of Bhallátaki (Semicarpus Anacardium), and by observing the spots where elephants slept or sat before or left dungs, or where they had just destroyed the banks of rivers or lakes. They shall also precisely ascertain whether any mark is due to the movements of elephants in herds, of an elephant roaming single, of a stray elephant, of a leader of herds, of a tusker, of a rogue elephant, of an elephant in rut, of a young elephant, or of an elephant that has escaped from the cage.

Experts in catching elephants shall follow the instructions given to them by the elephant doctor (aníkastha) and catch such elephants as are possessed of auspicious characteristics and good character.

The victory of kings (in battles) depends mainly upon elephants; for elephants, being of large bodily frame, are capable not only to destroy the arrayed army of an enemy, his fortifications, and encampments, but also to undertake works that are dangerous to life.

Elephants bred in countries, such as Kálinga, Anga, Karúsa, and the East are the best; those of the Dasárna and western countries are of middle quality; and those of Sauráshtra and Panchajana countries are of low quality. The might and energy of all can, however, be improved by suitable training.

[Thus ends Chapter II, “Division of Land” in Book II, “The Duties of Government Superintendents” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of twenty-third chapter from the beginning.]

CHAPTER III. CONSTRUCTION OF FORTS

ON all the four quarters of the boundaries of the kingdom, defensive fortifications against an enemy in war shall be constructed on grounds best fitted for the purpose: a water-fortification (audaka) such as an island in the midst of a river, or a plain surrounded by low ground; a mountainous fortification (párvata) such as a rocky tract or a cave; a desert (dhánvana) such as a wild tract devoid of water and overgrown with thicket growing in barren soil; or a forest fortification (vanadurga) full of wagtail (khajana), water and thickets.

Of these, water and mountain fortifications are best suited to defend populous centres; and desert and forest fortifications are habitations in wilderness (atavísthánam).

Or with ready preparations for flight the king may have his fortified capital (stháníya) as the seat of his sovereignty (samudayásthánam) in the centre of his kingdom: in a locality naturally best fitted for the purpose, such as the bank of the confluence of rivers, a deep pool of perennial water, or of a lake or tank, a fort, circular, rectangular, or square in form, surrounded with an artificial canal of water, and connected with both land and water paths (may be constructed).

Round this fort, three ditches with an intermediate space of one danda (6 ft.) from each other, fourteen, twelve and ten dandas respectively in width, with depth less by one quarter or by one-half of their width, square at their bottom and one-third as wide as at their top, with sides built of stones or bricks, filled with perennial flowing water or with water drawn from some other source, and possessing crocodiles and lotus plants shall be constructed.

At a distance of four dandas (24 ft.) from the (innermost) ditch, a rampart six dandas high and twice as much broad shall be erected by heaping mud upwards and by making it square at the bottom, oval at the centre pressed by the trampling of elephants and bulls, and planted with thorny and poisonous plants in bushes. Gaps in the rampart shall be filled up with fresh earth.

Above the rampart, parapets in odd or even numbers and with an intermediate, space of from 12 to 24 hastas from each other shall be built of bricks and raised to a height of twice their breadth.

The passage for chariots shall be made of trunks of palm trees or of broad and thick slabs of stones with spheres like the head of a monkey carved on their surface; but never of wood as fire finds a happy abode in it.

Towers, square throughout and with moveable staircase or ladder equal to its height, shall also be constructed.

In the intermediate space measuring thirty dandas between two towers, there shall be formed a broad street in two compartments covered over with a roof and two-and- half times as long as it is broad.

Between the tower and the broad street there shall be constructed an Indrakósa which is made up of covering pieces of wooden planks affording seats for three archers.

There shall also be made a road for Gods which shall measure two hastas inside (the towers ?), four times as much by the sides, and eight hastas along the parapet.

Paths (chárya, to ascend the parapet ?) as broad as a danda (6 ft.) or two shall also be made.

In an unassailable part (of the rampart), a passage for flight (pradhávitikám), and a door for exit (nishkuradwáram) shall be made.

Outside the rampart, passages for movements shall be closed by forming obstructions such as a knee-breaker (jánubhanjaní), a trident, mounds of earth, pits, wreaths of thorns, instruments made like the tail of a snake, palm leaf, triangle, and of dog's teeth, rods, ditches filled with thorns and covered with sand, frying pans and water-pools.

Having made on both sides of the rampart a circular hole of a danda-and-a-half in diametre, an entrance gate (to the fort) one-sixth as broad as the width of the street shall be fixed.

A square (chaturásra) is formed by successive addition of one danda up to eight dandas commencing from five, or in the proportion, one-sixth of the length up to one-eighth.

The rise in level (talotsedhah) shall be made by successive addition of one hasta up to 18 hastas commencing from 15 hastas.

In fixing a pillar, six parts are to form its height, on the floor, twice as much (12 parts) to be entered into the ground, and one-fourth for its capital.

Of the first floor, five parts (are to be taken) for the formation of a hall (sálá), a well, and a boundary-house; two-tenths of it for the formation of two platforms opposite to each other (pratimanchau); an upper storey twice as high as its width; carvings of images; an upper-most storey, half or three-fourths as broad as the first floor; side walls built of bricks; on the left side, a staircase circumambulating from left to right; on the right, a secret staircase hidden in the wall; a top-support of ornamental arches (toranasirah) projecting as far as two hastas; two door-panels, (each) occupying three-fourths of the space; two and two cross-bars (parigha, to fasten the door); an iron-bolt (indrakila) as long as an aratni (24 angulas); a boundary gate (ánidváram) five hastas in width; four beams to shut the door against elephants; and turrets (hastinakha) (outside the rampart) raised up to the height of the face of a man, removable or irremovable, or made of earth in places devoid of water.

A turret above the gate and starting from the top of the parapet shall be constructed, its front resembling an alligator up to three-fourths of its height.

In the centre of the parapets, there shall be constructed a deep lotus pool; a rectangular building of four compartments, one within the other; an abode of the Goddess Kumiri (Kumárípuram), having its external area one-and-a-half times as broad as that of its innermost room; a circular building with an arch way; and in accordance with available space and materials, there shall also be constructed canals (kulyá) to hold weapons and three times as long as broad.

In those canals, there shall be collected stones, spades (kuddála), axes (kuthári), varieties of staffs, cudgel (musrinthi), hammers (mudgara), clubs, discus, machines (yantra), and such weapons as can destroy a hundred persons at once (sataghni), together with spears, tridents, bamboo-sticks with pointed edges made of iron, camel-necks, explosives (agnisamyógas), and whatever else can be devised and formed from available materials.

[Thus ends Chapter III, "Construction of Forts,” in Book II, “The Duties of Government Superintendents” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of twenty-fourth chapter from the beginning.]

CHAPTER IV. BUILDINGS WITHIN THE FORT.

DEMARCATION of the ground inside the fort shall be made first by opening three royal roads from west to east and three from south to north.

The fort shall contain twelve gates, provided with both a land and water-way kept secret.

Chariot-roads, royal roads, and roads leading to drónamukha, stháníya, country parts, and pasture grounds shall each be four dandas (24 ft.) in width.

Roads leading to sayóníya (?), military stations (vyúha), burial or cremation grounds, and to villages shall be eight dandas in width.

Roads to gardens, groves, and forests shall be four dandas.

Roads leading to elephant forests shall be two dandas.

Roads for chariots shall be five aratnis (7½ ft.). Roads for cattle shall measure four aratnis; and roads for minor quadrupeds and men two aratnis.

Royal buildings shall be constructed on strong grounds.

In the midst of the houses of the people of all the four castes and to the north from the centre of the ground inside the fort, the king’s palace, facing either the north or the east shall, as described elsewhere (Chapter XX, Book I), be constructed occupying one-ninth of the whole site inside the fort.

Royal teachers, priests, sacrificial place, water-reservoir and ministers shall occupy sites east by north to the palace.

Royal kitchen, elephant stables, and the store-house shall be situated on sites east by south.

On the eastern side, merchants trading in scents, garlands, grains, and liquids, together with expert artisans and the people of Kshatriya caste shall have their habitations.

The treasury, the accountant’s office, and various manufactories (karmanishadyáscha) shall be situated on sites south by east.

The store-house of forest produce and the arsenal shall be constructed on sites south by west.

To the south, the superintendents of the city, of commerce, of manufactories, and of the army as well as those who trade in cooked rice, liquor, and flesh, besides prostitutes, musicians, and the people of Vaisya caste shall live.

To the west by south, stables of asses, camels, and working house.

To the west by north, stables of conveyances and chariots.

To the west, artisans manufacturing worsted threads, cotton threads, bamboo-mats, skins, armours, weapons, and gloves as well as the people of Súdra caste shall have their dwellings.

To the north by west, shops and hospitals.

To the north by east, the treasury and the stables of cows and horses.

To the north, the royal tutelary deity of the city, ironsmiths, artisans working on precious stones, as well as Bráhmans shall reside.

In the several corners, guilds and corporations of workmen shall reside.

In the centre of the city, the apartments of Gods such as Aparájita, Apratihata, Jayanta, Vaijayanta, Siva, Vaisravana, Asvina (divine physicians), and the honourable liquor-house (Srí-madiragriham), shall be situated.

In the corners, the guardian deities of the ground shall be appropriately set up.

Likewise the principal gates such as Bráhma, Aindra, Yámya, and Sainápatya shall be constructed; and at a distance of 100 bows (dhanus = 108 angulas) from the ditch (on the counterscarp side), places of worship and pilgrimage, groves and buildings shall be constructed.

Guardian deities of all quarters shall also be set up in quarters appropriate to them.

Either to the north or the east, burial or cremation grounds shall be situated; but that of the people of the highest caste shall be to the south (of the city).

Violation of this rule shall be punished with the first amercement.

Heretics and Chandálas shall live beyond the burial grounds.

Families of workmen may in any other way be provided with sites befitting with their occupation and field work. Besides working in flower-gardens, fruit-gardens, vegetable-gardens, and paddy-fields allotted to them, they (families) shall collect grains and merchandise in abundance as authorised.

There shall be a water-well for every ten houses.

Oils, grains, sugar, salt, medicinal articles, dry or fresh vegetables, meadow grass, dried flesh, haystock, firewood, metals, skins, charcoal, tendons (snáyu), poison, horns, bamboo, fibrous garments, strong timber, weapons, armour, and stones shall also be stored (in the fort) in such quantities as can be enjoyed for years together without feeling any want. Of such collection, old things shall be replaced by new ones when received.

Elephants, cavalry, chariots, and infantry shall each be officered with many chiefs inasmuch as chiefs, when many, are under the fear of betrayal from each other and scarcely liable to the insinuations and intrigues of an enemy.

The same rule shall hold good with the appointment of boundary, guards, and repairers of fortifications.

Never shall báhirikas who are dangerous to the well being of cities and countries be kept in forts. They may either be thrown in country parts or compelled to pay taxes.

[Thus ends Chapter IV, “ Buildings within the Fort” in Book II, “The Duties of the Government Superintendents” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of twenty-fifth chapter from the beginning.]

QuoteCHAPTER XVIII. THE SUPERINTENDENT OF THE ARMOURY.

THE Superintendent of the Armoury shall employ experienced workmen of tried ability to manufacture in a given time and for fixed wages wheels, weapons, mail armour, and other accessory instruments for use in battles, in the construction or defence of forts, or in destroying the cities or strongholds of enemies.

All these weapons and instruments shall be kept in places suitably prepared for them. They shall not only be frequently dusted and transferred from one place to another, but also be exposed to the sun. Such weapons as are likely to be affected by heat and vapour (úshmopasneha) and to be eaten by worms shall be kept in safe localities. They shall also be examined now and then with reference to the class to which they belong, their forms, their characteristics, their size, their source, their value, and their total quantity.

Sarvatobhadra, jamadagnya, bahumukha, visvásagháti, samgháti, yánaka, parjanyaka, ardhabáhu, and úrdhvabáhu are immoveable machines (sthirayantrám).

Pánchálika, devadanda, súkarika, musala, yashti, hastiváraka, tálavrinta, mudgara, gada, spriktala, kuddála, ásphátima, audhghátima, sataghni, trisúla, and chakra are moveable machines.

Sakti, prása, kunta, hátaka, bhindivála, súla, tomara, varáhakarna, kanaya, karpana, trásika, and the like are weapons with edges like a ploughshare (halamukháni).

Bows made of tála (palmyra), of chápa (a kind of bamboo), of dáru (a kind of wood), and sringa (bone or horn) are respectively called kármuka, kodanda, druna, and dhanus.

Bow-strings are made of múrva (Sansviera Roxburghiana), arka (Catotropis Gigantea), sána (hemp), gavedhu (Coix Barbata), venu (bamboo bark), and snáyu (sinew).

Venu, sara, saláka, dandásana, and nárácha are different kinds of arrows. The edges of arrows shall be so made of iron, bone or wood as to cut, rend or pierce.

Nistrimsa, mandalágra, and asiyashti are swords. The handles of swords are made of the horn of rhinoceros, buffalo, of the tusk of elephants, of wood, or of the root of bamboo.

Parasu, kuthára, pattasa, khanitra, kuddála, chakra, and kándachchhedana are razor-like weapons.

Yantrapáshána, goshpanapáshána, mushtipáshána, rochaní (mill-stone), and stones are other weapons (áyudháni).

Lohajáliká, patta, kavacha, and sútraka are varieties of armour made of iron or of skins with hoofs and horns of porpoise, rhinoceros, bison, elephant or cow.

Likewise sirastrána (cover for the head), kanthatrána (cover for the neck) kúrpása (cover for the trunk), kanchuka (a coat extending as far as the knee joints), váravána (a coat extending as far as the heels), patta, (a coat without cover for the arms), and nágodariká (gloves) are varieties of armour.

Veti, charma, hastikarna, tálamúla, dharmanika, kaváta, kitika, apratihata, and valáhakánta are instruments used in self-defence (ávaranáni).

Ornaments for elephants, chariots, and horses as well as goads and hooks to lead them in battle-fields constitute accessory things (upakaranáni).

(Besides the above) such other delusive and destructive contrivances (as are treated of in Book XIV) together with any other new inventions of expert workmen (shall also be kept in stock.)

The Superintendent of Armoury shall precisely ascertain the demand and supply of weapons, their application, their wear and tear, as well as their decay and loss.

[Thus ends Chapter XVIII, “The Superintendent of the Armoury” in Book II, “The Duties of Government Superintendents,” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of thirty-ninth chapter from the beginning.]

QuoteCHAPTER XXXII. TRAINING OF ELEPHANTS.

ELEPHANTS are classified into four kinds in accordance with the training they are given: that which is tameable (damya), that which is trained for war (sánnáhya), that which is trained for riding (aupaváhya), and rogue elephants (vyála).

Those which are tameable fall under five groups: that which suffers a man to sit on its withers (skandhagata), that which allows itself to be tethered to a post (stambhagata), that which can be taken to water (várigata), that which lies in pits (apapátagata), and that which is attached to its herd (yúthagata).

All these elephants shall be treated with as much care as a young elephant (bikka).

Military training is of seven kinds: Drill (upasthána), turning (samvartana), advancing (samyána), trampling down and killing (vadhávadha), fighting with other elephants (hastiyuddha), assailing forts and cities (nágaráyanam), and warfare.

Binding the elephants with girths (kakshyákarma), putting on collars (graiveyakakarma), and making them work in company with their herds (yúthakarma) are the first steps (upa-vichara) of the above training.

Elephants trained for riding fall under seven groups: that which suffers a man to mount over it when in company with another elephant (kunjaropaváhya), that which suffers riding when led by a warlike elephant (sánnáhyopaváhya), that which is taught trotting (dhorana), that which is taught various kinds of movements (ádhánagatika), that which can be made to move by using a staff (yashtyupaváhya), that which can be made to move by using an iron hook (totropaváhya), that which can be made to move without whips (suddhopaváhya), and that which is of help in hunting.

Autumnal work (sáradakarma), mean or rough work (hínakarma), and training to respond to signals are the first steps for the above training.

Rogue elephants can be trained only in one way. The only means to keep them under control is punishment. It has a suspicious aversion to work, is obstinate, of perverse nature, unsteady, willful, or of infatuated temper under the influence of rut.

Rogue elephants whose training proves a failure may be purely roguish (suddha), clever in roguery (suvrata), perverse (vishama), or possessed of all kinds of vice.

The form of fetters and other necessary means to keep them under control shall be ascertained from the doctor of elephants.

Tetherposts (álána), collars, girths, bridles, legchains, frontal fetters are the several kinds of binding instruments.

A hook, a bamboo staff, and machines (yantra) are instruments.

Necklaces such as vaijavantí and kshurapramála, and litter and housings are the ornaments of elephants.

Mail-armour (varma), clubs (totra), arrow-bags, and machines are war-accoutrements.

Elephant doctors, trainers, expert riders, as well as those who groom them, those who prepare their food, those who procure grass for them, those who tether them to posts, those who sweep elephant stables, and those who keep watch in the stables at night, are some of the persons that have to attend to the needs of elephants.

Elephant doctors, watchmen, sweepers, cooks and others shall receive (from the storehouse,) 1 prastha of cooked rice, a handful of oil, land 2 palas of sugar and of salt. Excepting the doctors, others shall also receive 10 palas of flesh.

Elephant doctors shall apply necessary medicines to elephants which, while making a journey, happen to suffer from disease, overwork, rut, or old age.

Accumulation of dirt in stables, failure to supply grass, causing an elephant to lie down on hard and unprepared ground, striking on vital parts of its body, permission to a stranger to ride over it, untimely riding, leading it to water through impassable places, and allowing it to enter into thick forests are offences punishable with fines. Such fines shall be deducted from the rations and wages due to the offenders.

During the period of Cháturmásya (the months of July, August, September and October) and at the time when two seasons meet, waving of lights shall be performed thrice. Also on new-moon and full-moon days, commanders shall perform sacrifices to Bhútas for the safety of elephants.

Leaving as much as is equal to twice the circumference of the tusk near its root, the rest of the tusks shall be cut off once in 2½ years in the case of elephants born in countries irrigated by rivers (nadija), and once in 5 years in the case of mountain elephants.

[Thus ends Chapter XXXII, “The Training of Elephants” in Book II, “The Duties of Government Superintendents” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the fifty-third chapter from the beginning.]

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE SUPERINTENDENT OF CHARIOTS; THE SUPERINTENDENT OF INFANTRY AND THE DUTY OF THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF.

THE functions of the Superintendent of horses will explain those of the Superintendent of chariots.

The Superintendent of chariots shall attend to the construction of chariots.

The best chariot shall measure 10 purushas in height (,i.e., 120 angulas), and 12 purushas in width. After this model, 7 more chariots with width decreasing by one purusha successively down to a chariot of 6 purushas in width shall be constructed. He shall also construct chariots of gods (devaratha), festal chariots (pushyaratha), battle chariots (sángrámika), travelling chariots (páriyánika), chariots used in assailing an enemy's strong-holds (parapurabhiyánika), and training chariots.

He shall also examine the efficiency in the training of troops in shooting arrows, in hurling clubs and cudgels, in wearing mail armour, in equipment, in charioteering, in fighting seated on a chariot, and in controlling chariot horses.

He shall also attend to the accounts of provision and wages paid to those who are either permanently or temporarily employed (to prepare chariots and other things). Also he shall take steps to maintain the employed contented and happy by adequate reward (yogyarakshanushthánam), and ascertain the distance of roads.

The same rules shall apply to the superintendent of infantry.

The latter shall know the exact strength or weakness of hereditary troops (maula), hired troops (bhrita), the corporate body of troops (sreni), as well as that of the army of friendly or unfriendly kings and of wild tribes.

He shall be thoroughly familiar with the nature of fighting in low grounds, of open battle, of fraudulent attack, of fighting under the cover of entrenchment (khanakayuddha), or from heights (ákásayuddha), and of fighting during the day and night, besides the drill necessary for such warfare.

He shall also know the fitness or unfitness of troops on emergent occasions.

With an eye to the position which the entire army (chaturangabala) trained in the skillful handling of all kinds of weapons and in leading elephants, horses, and chariots have occupied and to the emergent call for which they ought to be ready, the commander-in-chief shall be so capable as to order either advance or retreat (áyogamayógam cha).

He shall also know what kind of ground is more advantageous to his own army, what time is more favourable, what the strength of the enemy is, how to sow dissension in an enemy's army of united mind, how to collect his own scattered forces, how to scatter the compact body of an enemy's army, how to assail a fortress, and when to make a general advance.

Being ever mindful of the discipline which his army has to maintain not merely in camping and marching, but in the thick of battle, he shall designate the regiments (vyúha) by the names of trumpets, boards, banners, or flags.

[Thus ends Chapter XXXIII, "The Superintendent of Chariots, the Superintendent of Infantry, and the Duties of the Commander-in-Chief " in Book II, "The Duties of Government Superintendents" of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the fifty-fourth chapter from the beginning.]

QuoteCHAPTER II. THE TIME OF RECRUITING THE ARMY; THE FORM OF EQUIPMENT; AND THE WORK OF ARRAYING A RIVAL FORCE.

THE time of recruiting troops, such as hereditary troops (maula), hired troops, corporation of soldiers (srení), troops belonging to a friend or to an enemy, and wild tribes.

When he (a king) thinks that his hereditary army is more than he requires for the defence of his own possessions or when he thinks that as his hereditary army consists of more men than he requires, some of them may be disaffected; or when he thinks that his enemy has a strong hereditary army famous for its attachment, and is, therefore, to be fought out with much skill on his part; or when he thinks that though the roads are good and the weather favourable, it is still the hereditary army that can endure wear and tear; or when he thinks that though they are famous for their attachment, hired soldiers and other kinds of troops cannot be relied upon lest they might lend their ears to the intrigues of the enemy to be invaded; or when he thinks that other kinds of force are wanting in strength, then is the time for taking the hereditary army.

When he thinks that the army he has hired is greater than his hereditary army; that his enemy's hereditary army is small and disaffected, while the army his enemy has hired is insignificant and weak; that actual fight is less than treacherous fight; that the place to be traversed and the time required do not entail much loss; that his own army is little given to stupor, is beyond the fear of intrigue, and is reliable; or that little is the enemy's power which he has to put down, then is the time for leading the hired army.

When he thinks that the immense corporation of soldiers he possesses can be trusted both to defend his country and to march against his enemy; that he has to be absent only for a short time; or that his enemy's army consists mostly of soldiers of corporations, and consequently the enemy is desirous of carrying on treacherous fight rather than an actual war, then is the time for the enlistment of corporations of soldiers (srení).

When he thinks that the strong help he has in his friend can be made use of both in his own country and in his marches; that he has to be absent only for a short time, and actual fight is more than treacherous fight; that having made his friend's army to occupy wild tracts, cities, or plains and to fight with the enemy's ally, he, himself, would lead his own army to fight with the enemy's army; that his work can be accomplished by his friend as well; that his success depends on his friend; that he has a friend near and deserving of obligation; or that he has to utilize the excessive force of his friend, then is the time for the enlistment of a friend's army.

When he thinks that he will have to make his strong enemy to fight against another enemy on account of a city, a plain, or a wild tract of land, and that in that fight he will achieve one or the other of his objects, just like an outcast person in the fight between a dog and a pig; that through the battle, he will have the mischievous power of his enemy's allies or of wild tribes destroyed; that he will have to make his immediate and powerful enemy to march elsewhere and thus get rid of internal rebellion which his enemy might have occasioned; and that the time of battle between enemies or between inferior kings has arrived, then is the time for the exercise of an enemy's forces.

This explains the time for the engagement of wild tribes.

When he thinks that the army of wild tribes is living by the same road (that his enemy has to traverse); that the road is unfavourable for the march of his enemy's army; that his enemy's army consists mostly of wild tribes; that just as a wood-apple (bilva) is broken by means of another wood-apple, the small army of his enemy is to be destroyed, then is the time for engaging the army of wild tribes.

That army which is vast and is composed of various kinds of men and is so enthusiastic as to rise even without provision and wages for plunder when told or untold; that which is capable of applying its own remedies against unfavourable rains; that which can be disbanded and which is invincible for enemies; and that, of which all the men are of the same country, same caste, and same training, is (to be considered as) a compact body of vast power.

Such are the periods of time for recruiting the army.

Of these armies, one has to pay the army of wild tribes either with raw produce or with allowance for plunder.

When the time for the march of one's enemy's army has approached, one has to obstruct the enemy or send him far away, or make his movements fruitless, or, by false promise, cause him to delay the march, and then deceive him after the time for his march has passed away. One should ever be vigilant to increase one's own resources and frustrate the attempts of one's enemy to gain in strength.

Of these armies, that which is mentioned first is better than the one subsequently mentioned in the order of enumeration.

Hereditary army is better than hired army inasmuch as the former has its existence dependent on that of its master, and is constantly drilled.

That kind of hired army which is ever near, ready to rise quickly, and obedient, is better than a corporation of soldiers.

That corporation of soldiers which is native, which has the same end in view (as the king), and which is actuated with similar feelings of rivalry, anger, and expectation of success and gain, is better than the army of a friend. Even that corporation of soldiers which is further removed in place and time is, in virtue of its having the same end in view, better than the army of a friend.

The army of an enemy under the leadership of an Arya is better than the army of wild tribes. Both of them (the army of an enemy and of wild tribes) are anxious for plunder. In the absence of plunder and under troubles, they prove as dangerous as a lurking snake.

My teacher says that of the armies composed of Bráhmans, Kshatriyas, Vaisyas, or Súdras, that which is mentioned first is, on account of bravery, better to be enlisted than the one subsequently mentioned in the order of enumeration.

No, says Kautilya, the enemy may win over to himself the army of Bráhmans by means of prostration. Hence, the army of Kshatriyas trained in the art of wielding weapons is better; or the army of Vaisyas or Súdras having great numerical strength (is better).

Hence one should recruit one’s army, reflecting that "such is the army of my enemy; and this is my army to oppose it."

The army which possesses elephants, machines, sakatagarbha (?), Kunta (a wooden rod), prása (a weapon, 24 inches long, with two handles), Kharvataka (?), bamboo sticks, and iron sticks is the army to oppose an army of elephants.

The same possessed of stones, clubs, armour, hooks, and spears in plenty is the army to oppose an army of chariots.

The same is the army to oppose cavalry.

Men, clad in armour, can oppose elephants.

Horses can oppose men, clad in armour.

Men , clad in armour, chariots, men possessing defensive weapons, and infantry can oppose an army consisting of all the four constituents (elephants, chariots, cavalry and infantry).

Thus considering the strength of the constituents of one’s own quadripartite army, one should recruit men to it so as to oppose an enemy’s army successfully.

[Thus ends Chapter II, "The Time of Recruiting the Army, the Form of Equipment, and the Work of Arraying a Rival Force," in Book IX, "The Work of an Invader," of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the hundred and twenty-third chapter from the beginning.]

QuoteCHAPTER III. FORMS OF TREACHEROUS FIGHTS; ENCOURAGEMENT TO ONE'S OWN ARMY AND FIGHT BETWEEN ONE'S OWN AND ENEMY'S ARMIES.

HE who is possessed of a strong army, who has succeeded in his intrigues, and who has applied remedies against dangers may undertake an open fight, if he has secured a position favourable to himself; otherwise a treacherous fight.

He should strike the enemy when the latter's army is under troubles or is furiously attacked; or he who has secured a favourable position may strike the enemy entangled in an unfavourable position. Or he who possesses control over the elements of his own state may, through the aid of the enemy's traitors, enemies and inimical wild tribes, make a false impression of his own defeat on the mind of the enemy who is entrenched in a favourable position, and having thus dragged the enemy into an unfavourable position, he may strike the latter. When the enemy's army is in a compact body, he should break it by means of his elephants; when the enemy has come down from its favourable position, following the false impression of the invader's defeat, the invader may turn back and strike the enemy's army, broken or unbroken. Having struck the front of the enemy's army, he may strike it again by means of his elephants and horses when it has shown its back and is running away. When frontal attack is unfavourable, he should strike it from behind; when attack on the rear is unfavourable, he should strike it in front; when attack on one side is unfavourable, he should strike it on the other.

Or having caused the enemy to fight with his own army of traitors, enemies and wild tribes, the invader should with his fresh army strike the enemy when tired. Or having through the aid of the army of traitors given to the enemy the impression of defeat, the invader with full confidence in his own strength may allure and strike the over-confident enemy. Or the invader, if he is vigilant, may strike the careless enemy when the latter is deluded with the thought that the invader's merchants, camp and carriers have been destroyed. Or having made his strong force look like a weak force, he may strike the enemy's brave men when falling against him. Or having captured the enemy's cattle or having destroyed the enemy's dogs (svapadavadha?), he may induce the enemy's brave men to come out and may slay them. Or having made the enemy's men sleepless by harassing them at night, he may strike them during the day, when they are weary from want of sleep and are parched by heat, himself being under the shade. Or with his army of elephants enshrouded with cotton and leather dress, he may offer a night-battle to his enemy. Or he may strike the enemy's men during the afternoon when they are tired by making preparations during the forenoon; or he may strike the whole of the enemy's army when it is facing the sun.

A desert, a dangerous spot, marshy places, mountains, valleys, uneven boats, cows, cart-like array of the army, mist, and night are sattras (temptations alluring the enemy against the invader).

The beginning of an attack is the time for treacherous fights.

As to an open or fair fight, a virtuous king should call his army together, and, specifying the place and time of battle, address them thus: "I am a paid servant like yourselves; this country is to be enjoyed (by me) together with you; you have to strike the enemy specified by me."

His minister and priest should encourage the army by saying thus:--

"It is declared in the Vedas that the goal which is reached by sacrificers after performing the final ablutions in sacrifices in which the priests have been duly paid for is the very goal which brave men are destined to attain." About this there are the two verses--

Beyond those places which Bráhmans, desirous of getting into heaven, attain together with their sacrificial instruments by performing a number of sacrifices, or by practising penance are the places which brave men, losing life in good battles, are destined to attain immediately.

Let not a new vessel filled with water, consecrated and covered over with darbha grass be the acquisition of that man who does not fight in return for the subsistence received by him from his master, and who is therefore destined to go to hell.

Astrologers and other followers of the king should infuse spirit into his army by pointing out the impregnable nature of the array of his army, his power to associate with gods, and his omnisciency; and they should at the same time frighten the enemy. The day before the battle, the king should fast and lie down on his chariot with weapons. He should also make oblations into the fire pronouncing the mantras of the Atharvaveda, and cause prayers to be offered for the good of the victors as well as of those who attain to heaven by dying in the battle-field. He should also submit his person to Bráhmans; he should make the central portion of his army consist of such men as are noted for their bravery, skill, high birth, and loyalty and as are not displeased with the rewards and honours bestowed on them. The place that is to be occupied by the king is that portion of the army which is composed of his father, sons, brothers, and other men, skilled in using weapons, and having no flags and head-dress. He should mount an elephant or a chariot, if the army consists mostly of horses; or he may mount that kind of animal, of which the army is mostly composed or which is the most skillfully trained. One who is disguised like the king should attend to the work of arraying the army.

Soothsayers and court bards should describe heaven as the goal for the brave and hell for the timid; and also extol the caste, corporation, family, deeds, and character of his men. The followers of the priest should proclaim the auspicious aspects of the witchcraft performed. Spies, carpenters and astrologers should also declare the success of their own operations and the failure of those of the enemy.

After having pleased the army with rewards and honours, the commander-in-chief should address it and say:--

A hundred thousand (panas) for slaying the king (the enemy); fifty thousand for slaying the commander-in-chief, and the heir-apparent; ten thousand for slaying the chief of the brave; five thousand for destroying an elephant, or a chariot; a thousand for killing a horse, a hundred (panas) for slaying the chief of the infantry; twenty for bringing a head; and twice the pay in addition to whatever is seized. This information should be made known to the leaders of every group of ten (men).

Physicians with surgical instruments (sastra), machines, remedial oils, and cloth in their hands; and women with prepared food and beverage should stand behind, uttering encouraging words to fighting men.

The army should be arrayed on a favourable position, facing other than the south quarter, with its back turned to the sun, and capable to rush as it stands. If the array is made on an unfavourable spot, horses should be run. If the army arrayed on an unfavourable position is confined or is made to run away from it (by the enemy), it will be subjugated either as standing or running away; otherwise it will conquer the enemy when standing or running away. The even, uneven, and complex nature of the ground in the front or on the sides or in the rear should be examined. On an even site, staff-like or circular array should be made; and on an uneven ground, arrays of compact movement or of detached bodies should be made.

Having broken the whole army (of the enemy), (the invader) should seek for peace; if the armies are of equal strength, he should make peace when requested for it; and if the enemy's army is inferior, he should attempt to destroy it, but not that which has secured a favourable position and is reckless of life.

When a broken army, reckless of life, resumes its attack, its fury becomes irresistible; hence he should not harass a broken army (of the enemy).

[Thus ends Chapter III, "Forms of Treacherous Fights; Encouragement to One's Own Army, and Fight Between One's Own and Enemy's Armies," in Book X, "Relating to War," of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the hundred and thirty-first chapter from the beginning.]

CHAPTER IV. BATTLEFIELDS; THE WORK OF INFANTRY, CAVALRY, CHARIOTS, AND ELEPHANTS.

FAVOURABLE positions for infantry, cavalry, chariots, and elephants are desirable both for war and camp.

For men who are trained to fight in desert tracts, forests, valleys, or plains, and for those who are trained to fight from ditches or heights, during the day or night, and for elephants which are bred in countries with rivers, mountains, marshy lands, or lakes, as well as for horses, such battlefields as they would find suitable (are to be secured).

That which is even, splendidly firm, free from mounds and pits made by wheels and foot-prints of beasts, not offering obstructions to the axle, free from trees, plants, creepers and trunks of trees, not wet, and free from pits, ant-hills, sand, and thorns is the ground for chariots.

For elephants, horses and men, even or uneven grounds are good, either for war or for camp.

That which contains small stones, trees and pits that can be jumped over and which is almost free from thorns is the ground for horses.

That which contains big stones, dry or green trees, and ant-hills is the ground for the infantry.

That which is uneven with assailable hills and valleys, which has trees that can be pulled down and plants that can be torn, and which is full of muddy soil free from thorns is the ground for elephants.

That which is free from thorns, not very uneven, but very expansive, is an excellent ground for the infantry.

That which is doubly expansive, free from mud, water and roots of trees, and which is devoid of piercing gravel is an excellent ground for horses.

That which possesses dust, muddy soil, water, grass and weeds, and which is free from thorns (known as dog's teeth) and obstructions from the branches of big trees is an excellent ground for elephants.

That which contains lakes, which is free from mounds and wet lands, and which affords space for turning is an excellent ground for chariots.

Positions suitable for all the constituents of the army have been treated of. This explains the nature of the ground which is fit for the camp or battle of all kinds of the army.

Concentration on occupied positions, in camps and forests; holding the ropes (of beasts and other things) while crossing the rivers or when the wind is blowing hard; destruction or protection of the commissariat and of troops arriving afresh; supervision of the discipline of the army; lengthening the line of the army; protecting the sides of the army; first attack; dispersion (of the enemy's army); trampling it down; defence; seizing; letting it out; causing the army to take a different direction; carrying the treasury and the princes; falling against the rear of the enemy; chasing the timid; pursuit; and concentration--these constitute the work of horses.

Marching in the front; preparing the roads, camping grounds and path for bringing water; protecting the sides; firm standing, fording and entering into water while crossing pools of water and ascending from them; forced entrance into impregnable places; setting or quenching the fire; the subjugation of one of the four constituents of the army; gathering the dispersed army; breaking a compact army; protection against dangers; trampling down (the enemy's army); frightening and driving it; magnificence; seizing; abandoning; destruction of walls, gates and towers; and carrying the treasury--these constitute the work of elephants.

Protection of the army; repelling the attack made by all the four constituents of the enemy's army; seizing and abandoning (positions) during the time of battle; gathering a dispersed army; breaking the compact array of the enemy's army; frightening it; magnificence; and fearful noise--these constitute the work of chariots.

Always carrying the weapons to all places; and fighting--these constitute the work of the infantry.

The examination of camps, roads, bridges, wells and rivers; carrying the machines, weapons, armours, instruments and provisions; carrying away the men that are knocked down, along with their weapons and armours---these constitute the work of free labourers.

The king who has a small number of horses may combine bulls with horses; likewise when he is deficient in elephants, he may fill up the centre of his army with mules, camels and carts.

[Thus ends Chapter IV, “Battlefields; the Work of Infantry, Cavalry, Chariots and Elephants,” in Book X, “Relating to War,” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the hundred and thirty-second chapter from the beginning.]

QuoteCHAPTER IV. THE OPERATION OF A SIEGE.

REDUCTION (of the enemy) must precede a siege. The territory that has been conquered should be kept so peacefully that it might sleep without any fear. When it is in rebellion, it is to be pacified by bestowing re- wards and remitting taxes, unless the conqueror means to quit it. Or he may select his battle fields in a remote part of the enemy's territory, far from the populous centres; for, in the opinion of Kautilya, no territory deserves the name of a kingdom or country unless it is full of people. When a people resist the attempt of the conqueror, then he may destroy their stores, crops, and granaries, and trade.

- By the destruction of trade, agricultural produce, and standing crops, by causing the people to run away, and by slaying their leaders in secret, the country will be denuded of its people.

When the conqueror thinks: "My army is provided with abundance of staple corn, raw materials, machines, weapons, dress, labourers, ropes and the like, and has a favourable season to act, whereas my enemy has an unfavourable season and is suffering from disease, famine and loss of stores and defencive force, while his hired troops as well as the army of his friend are in a miserable condition,"--then he may begin the siege.

Having well guarded his camp, transports, supplies and also the roads of communication, and having dug up a ditch and raised a rampart round his camp, he may vitiate the water in the ditches round the enemy's fort, or empty the ditches of their water or fill them with water if empty, and then he may assail the rampart and the parapets by making use of underground tunnels and iron rods. If the ditch (dváram) is very deep, he may fill it up with soil. If it is defended by a number of men, he may destroy it by means of machines. Horse soldiers may force their passage through the gate into the fort and smite the enemy. Now and then in the midst of tumult, he may offer terms to the enemy by taking recourse to one, two, three, or all of the strategic means.

Having captured the birds such as the vulture, crow, naptri, bhása, parrot, máina, and pigeon which have their nests in the fort-walls, and having tied to their tails inflammable powders (agniyoga), he may let them fly to the forts. If the camp is situated at a distance from the fort and is provided with an elevated post for archers and their flags, then the enemy's fort may be set on fire. Spies, living as watchmen of the fort, may tie inflammable powder to the tails of mongooses, monkeys, cats and dogs and let them go over the thatched roofs of the houses. A splinter of fire kept in the body of a dried fish may be caused to be carried off by a monkey, or a crow, or any other bird (to the thatched roofs of the houses).

Small balls prepared from the mixture of sarala (Pinus Longifolia), devadáru (deodár), pútitrina (stinking grass), guggulu (Bdellium), sriveshtaka (turpentine), the juice of sarja (Vatica Robusta), and láksha (lac) combined with dungs of an ass, camel, sheep, and goat are inflammable (agnidharanah, i.e., such as keep fire.)

The mixture of the powder of priyala (Chironjia Sapida), the charcoal of avalguja (oanyza, serratula, anthelmintica), madhúchchhishta (wax), and the dung of a horse, ass, camel, and cow is an inflammable powder to be hurled against the enemy.

The powder of all the metals (sarvaloha) as red as fire, or the mixture of the powder of kumbhí (gmelia arberea, sísa (lead), trapu (zinc), mixed with the charcoal powder of the flowers of páribhadraka (deodar), palása (Butea Frondosa), and hair, and with oil, wax, and turpentine, is also an inflammable powder.

A stick of visvásagháti painted with the above mixture and wound round with a bark made of hemp, zinc, and lead, is a fire-arrow (to be hurled against the enemy).

When a fort can be captured by other means, no attempt should be made to set fire to it; for fire cannot be trusted; it not only offends gods, but also destroys the people, grains, cattle, gold, raw materials and the like. Also the acquisition of a fort with its property all destroyed is a source of further loss. Such is the aspect of a siege.

When the conqueror thinks: "I am well provided with all necessary means and with workmen whereas my enemy is diseased with officers proved to be impure under temptations, with unfinished forts and deficient stores, allied with no friends, or with friends inimical at heart," then he should consider it as an opportune moment to take up arms and storm the fort.

When fire, accidental or intentionally kindled, breaks out; when the enemy's people are engaged in a sacrificial performance, or in witnessing spectacles or the troops, or in a quarrel due to the drinking of liquor; or when the enemy's army is too much tired by daily engagements in battles and is reduced in strength in consequence of the slaughter of a number of its men in a number of battles; when the enemy's people wearied from sleeplessness have fallen asleep; or on the occasion of a cloudy day, of floods, or of a thick fog or snow, general assault should be made.

Or having concealed himself in a forest after abandoning the camp, the conqueror may strike the enemy when the latter comes out.

A king pretending to be the enemy's chief friend or ally, may make the friendship closer with the besieged, and send a messenger to say: "This is thy weak point; these are thy internal enemies; that is the weak point of the besieger; and this person (who, deserting the conqueror, is now coming to thee) is thy partisan." When this partisan is returning with another messenger from the enemy, the conqueror should catch hold of him and, having published the partisan's guilt, should banish him, and retire from the siege operations. Then the pretending friend may tell the besieged: "Come out to help me, or let us combine and strike the besieger." Accordingly, when the enemy comes out, he may be hemmed between the two forces (the conqueror's force and the pretending friend's force) and killed or captured alive to distribute his territory (between the conqueror and the friend). His capital city may be razed to the ground; and the flower of his army made to come out and destroyed.

This explains the treatment of a conquered enemy or wild chief.

Either a conquered enemy or the chief of a wild tribe (in conspiracy with the conqueror) may inform the besieged: "With the intention of escaping from a disease, or from the attack in his weak point by his enemy in the rear, or from a rebellion in his army, the conqueror seems to be thinking of going elsewhere, abandoning the siege." When the enemy is made to believe this, the conqueror may set fire to his camp and retire. Then the enemy coming out may be hemmed . . . as before.

Or having collected merchandise mixed with poison, the conqueror may deceive the enemy by sending that merchandise to the latter.

Or a pretending ally of the enemy may send a messenger to the enemy, asking him: "Come out to smite the conqueror already struck by me." When he does so, he may be hemmed . . . as before.

Spies, disguised as friends or relatives and with passports and orders in their hands, may enter the enemy's fort and help to its capture.

Or a pretending ally of the enemy may send information to the besieged: "I am going to strike the besieging camp at such a time and place; then you should also fight along with me." When the enemy does so, or when he comes out of his fort after witnessing the tumult and uproar of the besieging army in danger, he may be slain as before.

Or a friend or a wild chief in friendship with the enemy may be induced and encouraged to seize the land of the enemy when the latter is besieged by the conqueror. When accordingly any one of them attempts to seize the enemy's territory, the enemy's people or the leaders of the enemy's traitors may be employed to murder him (the friend or the wild chief); or the conqueror himself may administer poison to him. Then another pretending friend may inform the enemy that the murdered person was a fratricide (as he attempted to seize the territory of his friend in troubles). After strengthening his intimacy with the enemy, the pretending friend may sow the seeds of dissension between the enemy and his officers and have the latter hanged. Causing the peaceful people of the enemy to rebel, he may put them down, unknown to the enemy. Then having taken with him a portion of his army composed of furious wild tribes, he may enter the enemy's fort and allow it to be captured by the conqueror. Or traitors, enemies, wild tribes and other persons who have deserted the enemy, may, under the plea of having been reconciled, honoured and rewarded, go back to the enemy and allow the fort to be captured by the conqueror.

Having captured the fort or having returned to the camp after its capture, he should give quarter to those of the enemy's army who, whether as lying prostrate in the field, or as standing with their back turned to the conqueror, or with their hair dishevelled, with their weapons thrown down or with their body disfigured and shivering under fear, surrender themselves. After the captured fort is cleared of the enemy's partisans and is well guarded by the conqueror's men both within and without, he should make his victorious entry into it.

Having thus seized the territory of the enemy close to his country, the conqueror should direct his attention to that of the madhyama king; this being taken, he should catch hold of that of the neutral king. This is the first way to conquer the world. In the absence of the madhyama and neutral kings, he should, in virtue of his own excellent qualities, win the hearts of his enemy's subjects, and then direct his attention to other remote enemies. This is the second way. In the absence of a Circle of States (to be conquered), he should conquer his friend or his enemy by hemming each between his own force and that of his enemy or that of his friend respectively. This is the third way.

Or he may first put down an almost invincible immediate enemy. Having doubled his power by this victory, he may go against a second enemy; having trebled his power by this victory, he may attack a third. This is the fourth way to conquer the world.

Having conquered the earth with its people of distinct castes and divisions of religious life, he should enjoy it by governing it in accordance with the duties prescribed to kings.

- Intrigue, spies, winning over the enemy's people, siege, and assault are the five means to capture a fort.

[Thus ends Chapter IV, "The Operation of a Siege and Storming a Fort," in Book XIII, "Strategic Means to Capture a Fortress," of the Arthasástra of Kautilya. End of the hundred and forty-fourth chapter from the beginning.]

-

3

3

-

To be precise, I am personally against the idea to build groups based on history and general strategical guidelines and to stick with those to balance the civs.

I understand that the civs belongs to the same conceptual groups due to their design, because in the way we design a faction we are constrained by historical evidences.

So it is logical that the Iberians, the Britons and the Gauls have several similarities in their strategies. Because historically they had. It is logical that Macedonians, Seleucids and Ptolemies have several similarities as well.

But I am against the idea to balance the civs only with their similar counterparts. If the Iberians, the Britons and the Gauls are only balanced in regard to each other, then it will probably result to unbalance when players of those civs will face other civs from other groups. Because let's face it, it would be the case regularly.

So I suggest those grouping should be different according to their goals. I agree to group the civs between them according to their similarities and history when it is done with the purpose to draw the general kind of strategies and gameplay. Like in Wijitmaker proposal with thematic group.

But when it is grouping in the purpose of balancing the civs, it should be mixed groups. Because it is not directly the civs that are unbalanced but some general strategies that are far better than others.

As I said, I agree with your observation that 78 matchups to balance is too much. I agree with your idea to balance the civs only in their own group. I simply don't see the relevance to balance a civ only against a similar civ.

-

2

2

-

-

4 hours ago, badosu said:

but I would like to keep it possible for players in the same tier to be have a decent matchup with wildly different civilizations.

Exactly. The issue with balancing very similar factions (the so-called "Celtic" group of European barbarians factions for example) will probably result in strong imbalance between the groups instead.

I don't see the need to make historical groups for a purely gameplay motive, eg balancing the civs.