-

Posts

2.320 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

71

Posts posted by Genava55

-

-

-

A game mixing RTS and FPS gameplay

-

1

1

-

-

On the social network VK, there is this page with a lot of interesting pictures: https://vk.com/scythians

There is also the account of Evgueni Kraї: https://vk.com/id387122112

-

1

1

-

-

@Stan` c'est fabuleux, si on écrit le mot P E T I T S, la censure détecte ça comme une grossièreté à cause des quatre dernières lettres.

-

1

1

-

-

Les Scythes, by Iaroslav Lebedynsky:

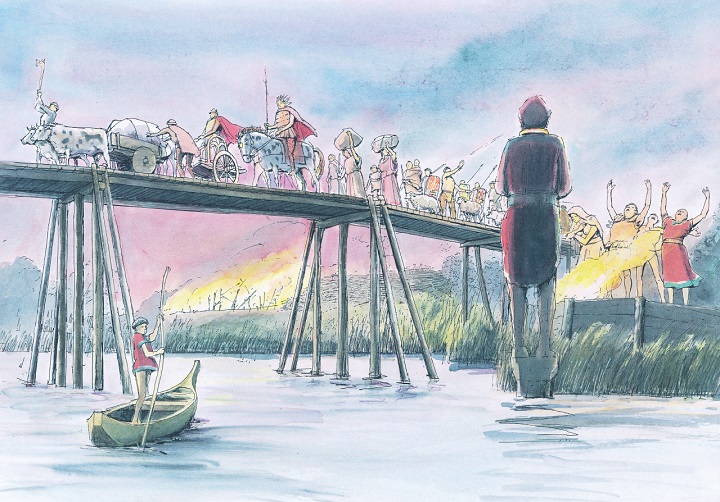

QuoteLa plupart des Scythes vivaient dans des chariots aménagés en habitations et dans des tentes, les rapports entre les deux n’étant d’ailleurs pas parfaitement clairs. Le Pseudo-Hippocrate [Des airs, des eaux et des lieux, XVIII) décrit les chariots scythes de façon assez détaillée et insiste sur leur rôle de “maisons sur roues” : “Ils n’ont pas d’habitations fixes et demeurent dans des chariots. Les plus pe@#$% de ces chariots sont à quatre roues, les autres en ont six ; ils sont fermés avec du feutre et construits comme des maisons, les uns n’ont qu’une chambre, les autres en ont trois. Ils sont impénétrables à la neige, à la pluie et aux vents. A ces chariots, on attelle deux ou trois paires de boeufs sans cornes. Dans de tels chariots vivent les femmes, et les hommes vont à cheval. ” Eschyle [Prométhée enchaîné) décrit également les “Scythes nomades qui habitent des demeures d’osier tressé juchées sur des chars à bonnes roues”. Le type le plus répandu devait être celui à quatre roues ; c’est en tout cas celui dont on retrouve normalement les traces dans les sépultures scythes. On imagine bien, en regardant les tapis et les étoffes préservés dans les “kourganes gelés” de l’Altaï, combien les compartiments pouvaient être rendus confortables. Si la caisse des chariots n’est guère connue, chez les Scythes d’Europe, que par la description du Pseudo-Hippocrate et quelques représentations (notamment des modèles réduits - probablement des jouets d’enfants - en terre cuite), de nombreuses roues ont été découvertes dans les tombes, dans un état qui permet de restituer leur structure. Leur étude donne une haute idée de la compétence technique de leurs fabricants. Elles étaient faites de bois et mesuraient entre 0,80 et 1,20 m de diamètre. Elles avaient de dix à douze rayons, et un moyeu en forme de cylindre ou de tonnelet aminci aux extrémités. Certaines comportaient des renforts métalliques, mais ce n’est pas systématique. On peut risquer un parallèle avec les lourds chariots de transport à quatre roues encore utilisés au XIXe siècle en Ukraine, notamment par les tchoumaks ou convoyeurs de sel qui les fabriquaient eux-mêmes mais achetaient les roues à des artisans spécialisés : les roues de bois n’étaient cerclées de fer que lorsqu’elles commençaient à se fendre ; des roues bien faites devaient pouvoir durer dix ans sans réparation. Les chariots d’habitation étaient certainement, compte tenu de leur poids, tirés par des boeufs, attelés au moyen d’un joug et d’un timon. Les nobles scythes en possédaient un grand nombre ; un personnage de l’un des romans scythes de Lucien de Samosate (Toxaris, XLVI) se vante de ses 80 chariots, et la comparaison avec les sociétés nomades médiévales ou modernes les mieux connues, comme les Mongols de l’époque impériale, suggère que ce nombre n’a rien d’invraisemblable. En ce qui concerne les tentes, on n’en possède pas de description (on ne peut considérer comme telle l’allusion d’Hérodote, IV, 23, au feutre, prétendument fixé à un arbre, sous lequel vivraient les lointains Argippéens : “Ils ont pour demeure le pied d’un arbre, entouré en hiver d’une tenture de feutre blanc imperméable, et sans ce feutre en été"’). Les espèces de tipis servant à l’inhalation des vapeurs de chanvre (Hérodote, IV, 73-75) ne sont pas des habitations. Chez les nomades des steppes européennes, la plus ancienne représentation de tente circulaire typiquement nomade (ce que l’on appelle improprement “yourte” en Occident) figure sur une fresque du tombeau d’Anthestêrios à Kertch (Ukraine, Crimée). Elle date de l’époque sarmate, et le modèle devait être connu des Scythes tardifs, si l’on en juge par les traces d’habitat de ce genre relevées dans leurs établissements (cf. chap. XI). Certains archéologues pensent que ces tentes pouvaient être montées sur des chariots, suivant une pratique attestée chez des peuples de la steppe à des époques plus récentes. Strabon (VII, 3, 17) semble évoquer ce système chez les nomades de son époque : “ Quant aux tentes des nomades, elles sont en feutre et solidement fixées aux chariots dans lesquels ils passent leur vie”. Les camps scythes, “villages sur roues”, devaient avoir la même ordonnance rigoureuse que les camps turcs ou mongols postérieurs.

Translation:

QuoteMost Scythians lived in wagons fitted out as dwellings and in tents, the relationship between the two not being entirely clear. The Pseudo-Hippocrates [On Airs, Waters and Places, XVIII) describes the Scythian chariots in some detail and insists on their role as “houses on wheels”: “They have no fixed dwellings and dwell in carts. The smallest of these carts have four wheels, the others have six; they are closed with felt and built like houses, some have only one bedroom, others have three. They are impenetrable to snow, rain and winds. To these carts are harnessed two or three pairs of polled oxen. In such carts live women, and men go on horseback. Aeschylus [Chained Prometheus) also describes the "nomadic Scythians who dwell in mansions of woven wicker perched on well-wheeled chariots." The most widespread type must have been the four-wheeled one; it is in any case the one whose traces are normally found in Scythian burials. One can imagine, looking at the carpets and fabrics preserved in the “frozen kurgans” of Altai, how comfortable the compartments could be made. If the body of the wagons is hardly known, among the Scythians of Europe, except by the description of Pseudo-Hippocrates and some representations (in particular reduced models - probably children's toys - in terracotta), many wheels were discovered in the tombs, in a state that allows their structure to be restored. Their study gives a high idea of the technical competence of their manufacturers. They were made of wood and measured between 0.80 and 1.20 m in diameter. They had ten to twelve spokes, and a cylindrical or keg-shaped hub tapered at the ends. Some had metal reinforcements, but this is not systematic. We can risk a parallel with the heavy four-wheeled transport carts still used in the 19th century in Ukraine, in particular by the chumaks or salt conveyors who made them themselves but bought the wheels from specialized craftsmen: wooden wheels n were bound with iron only when they began to split; well-made wheels should be able to last ten years without repair. The dwelling wagons were certainly, given their weight, drawn by oxen, hitched by means of a yoke and a drawbar. The noble Scythians possessed a large number of them; a character in one of Lucian of Samosata's Scythian romances (Toxaris, XLVI) boasts of his 80 chariots, and comparison with the better-known medieval or modern nomadic societies, such as the Mongols of the imperial era, suggests that there is nothing implausible about this number. As regards the tents, we have no description of them (one cannot consider as such the allusion of Herodotus, IV, 23, to the felt, supposedly fixed to a tree, under which the distant Argippeans would live: “ Their dwelling place is the foot of a tree, surrounded in winter by a curtain of waterproof white felt, and without this felt in summer". , 73-75) are not dwellings.Among the nomads of the European steppes, the oldest representation of a typically nomadic circular tent (what is improperly called a “yurt” in the West) appears on a fresco in the tomb of Anthesterios in Kerch (Ukraine, Crimea). It dates from the Sarmatian period, and the model must have been known to the late Scythians, if we judge by the traces of settlements of this type found in their settlements (cf. chap. XI) Some archaeologists think that these tents could be mounted on carts, following a practice attested among peoples of the steppe in more recent times. Strabo (VII, 3, 17) seems to evoke this system among the nomads of his time: “As for the tents of the nomads, they are made of felt and firmly attached to the carts in which they spend their lives”. The Scythian camps, “villages on wheels”, were to have the same rigorous order as the later Turkish or Mongol camps.

-

Developed and published by Juvly Worlds, Grimgrad is a strategy survival game. In this combat-free simulation, you are tasked with building a Slavic town during the Middle Ages on a grid-based map.

Grimgrad’s twist to the formula is the addition of Slavic gods and folklore that can affect gameplay. Appease the gods, and you’ll be rewarded. But, on the other hand, defy them and see all kinds of random events strike your settlement.

When you begin Grimgrad, you have a couple of options to choose from. First, a five-chapter story also acts as a tutorial, and there is an endless survival mode without specific goals. I started on the five-chapter story mode, and in each subsequent chapter, more gameplay opportunities opened up.

Also, the game itself becomes slightly more challenging. The tutorial keeps you on track, but I felt there was quite a bit of handholding from the tutorial, which is excellent for those players new to the genre. However, for experienced players like myself, I just wanted to get on with it and build.

The story in Gringrad is told in text-based still storyboards. As stories go, the storyline isn’t much different from the other survival simulation games I’ve played besides its Slavic theme. Something dire happens, and you have to rebuild seems to be the standard fare for survival games.

You witness the local village being burned down to the ground by the angry gods. Only young Jaromir, a direct descendent of the priestly line, manages to escape. Now Jaromir has to rebuild his village with the help of Semarglu, a fiery dog with wings, and protect the settlers and keep the gods happy.

-

I won't post pictures because I am tired of dealing with direct links on this forum.

But in general terms.

The most common helmets used by the Thracians are the Chalkidian and the Phrygian helmets. Phrygian helmets could have facial protections, as it was found with later variants discovered in noble burials.

The most common armors are “bell-shaped” cuirasses (similar to archaic Greek cuirasses) between 600 and 400 BC. Then there are armors with metallic scales and neck protective plates, like the armor found in Golyamata Mogila tumulus. Also the scaled armors depicted on Thracian plates, notably those from the treasure of Letnitsa.

-

2

2

-

-

1 hour ago, Duileoga said:

-¿Qué se le ocurre para las unidades @Genava55? si me pasan estos cascos tracios con sus texturas, podría intentar hacer algo en un tiempo cercano.

From a historical pov, Thracians were:

- Known for their peltasts and their ability to ambush and harass their enemies.

- Known for their light cavalry.

- Not known for their heavy infantry, their light infantry and light cavalry were able to fight in close combat but they didn't have the same efficiency than the heavy infantry and cavalry from the Greeks and Macedonians. Although their light infantry were able to use kopis and other curved swords to defend themselves.

- Known at some point for their slingers.

- Hiring Greek mercenaries/auxiliaries in some occasions, including hoplites.

- Hiring Getic mercenaries, known for their use of horse archery in some occasions.

I really encourage @Duileoga, @wowgetoffyourcellphone and @Ultimate Aurelian to read the following excerpts, I really think it will interest you and help you to figure out the strengths and weaknesses of the Thracians.

A few excerpts:

Thracian Warfare, a chapter in A Companion to Greek Warfare (2021):

QuoteFrom the later historical tradition, most notably Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon, one learns about the existence of different troop types and Thracian military tactics. The most common are the light-armed peltasts carrying two javelins, a crescent-shaped shield (pelte), and short swords (encheiridia). They wear fox fur hats, chitons covered with long cloaks called zeirai, and long boots of deerskin (Hdt. 7.75.1). This iconographic type of Thracian warrior circulated, predominantly on redfigure pottery, in the Greek world during the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Heavy infantry, on the other hand, or the hoplites derived from the Greek poleis, remained a foreign concept for the Thracians. The most significant role, reserved traditionally for Thracian nobles, was played by the cavalry, armed with spears, javelins, swords, and bows. The Odrysians and the Getae were especially notable as horse breeders. The figure of 50,000 horsemen, for instance, mustered by Sitalces during his march against the Macedonians in 429 is staggeringly high (Thuc. 2.98.3–4), a testimony to the vast potential of an economy based on horse breeding.

QuoteIn the multicolored mosaic of Thracian ethne, several qualities commonly expressed in military contexts and traditionally ascribed to Thracians immediately stand out. Thracians had the reputation of being good and courageous fighters, often depicted as fierce and warlike (Hdt. 7.111.1). They preferred marching and fighting under the cover of night. Upon giving battle they issued vociferous war cries, singing songs and performing war dances, while loudly clashing their weapons (Tacit. Ann. 4.47). The lack of heavy infantry allowed for greater flexibility and a mobile style of military conduct; very often the element of surprise assumed priority. The existence of the wedge formation, which the northern Thracians allegedly learned from the Scythians has been doubted, but on one occasion in 335, Arrian says, the Tribalians positioned themselves against Alexander, divided into a center and two flanks. On account of their maneuverability, Thracian peltasts became sought-after mercenaries after the march of Xerxes in Greece in 480, and especially during the Peloponnesian War and the war between Cyrus the Younger and Artaxerxes in 401.

QuoteIn the Hellenistic period, Thracian troops and techniques rulers had a profound impact of Greek warfare. For instance, the Athenian general Iphicrates, who married a daughter of Cotys (383–359), introduced reforms to the cumbersome panoply of Greek hoplites that showcased the effectiveness of Thracian peltasts during the Corinthian War (395–387). After the Macedonian conquest of Thrace by Philip II and Alexander III, Thracian cavalry and light-armed troops (psiloi) began to appear under the supervision of Macedonian and Thracian commanders. This practice continued during the Macedonian Wars, when Thracians fought in the armies of Philip V and Perseus against the Romans in the battles of Cynoscephalae (197), Callinicus (171), and Pydna (168). Thracians who served as mercenaries in the Ptolemaic armies eventually settled in Egypt as military colonists.

QuoteThe iron rhomphaia, that peculiar cross between a spear and a sickle, is possibly a Thracian invention that evolved from a farming implement. Thracians in Macedonian service carried it during the First and Second Macedonian Wars, but apparently only in the mountainous west and central Rhodopes. The slashing quality of the weapon made it effective against cavalry in the hands of light troops with small shields (thureoi). Why did this weapon come into use at this time, and not earlier? We do not know. Attempts to identify the weapon on scenes in painted Thracian tombs, e.g. Alexandrovo and Sveshtari, have proved unsatisfactory. An acceptance of this hypothesis still needs to explain why Thracians began to deposit rhomphaiai in graves during and after the First and Second Macedonian Wars, but not earlier.

QuoteThe Thracians, like the Scythians, made famous use of the composite bow, which appears in both grave assemblages and artistic representations. Graves of the late fifth and early fourth centuries have thus produced large numbers of bronze arrowheads (Robinson’s Type G1). The differing needs of hunters and warriors may explain various projectile sizes and separate quivers. Although Robinson’s Type G1 arrowheads continued to be used during the Hellenistic period, they crop up in settlements such as Pistiros, Kabyle, Dragoevo, and Seuthopolis, not in graves. They had proved ballistically inferior to Cretan arrowheads (Robinson’s Type D1) and to catapult projectiles made of iron (Robinson’s Type E), which arrived in Thrace with the Macedonian troops of Philip II, Alexander III and the Successors.

QuoteSling ammunition deposited in graves present another puzzle. Round stones or pebbles put in leather pouches appear conspicuously alongside other weapons in the aristocratic equestrian burials at Golemanite, Veliko Tarnovo, and Aghigiol, but scholars differ about whether they are ammunition. Perhaps they were thrown by hand rather than by a sling. Odrysians are mentioned as skillful stone-throwers (petroboloi) by the early fourth century. Lead sling bullets cast in matrices, on the other hand, arrived in Thrace only with the Macedonians.

Odrysian Cavalry Arms, Equipment, and Tactics (2003):

QuoteThe Odrysian army was composed mainly of peltasts and cavalry, the remainder being lighter infantry (javelin men, archers, and slingers). In Sitalkes army, these warriors came from the Odrysai, Getae, eastern Paionians (Agrianians and Laeaeans), Treres, Tilateans, Apsinthii, Krobyzi, Dii (plus Bessi and other mountain tribes), and Thyni. None of the tribes from the Aegean coast (Edoni, Bisaltae etc) joined Sitalkes.

QuoteGreek mercenaries were occasionally hired to make up for the lack of heavy infantry. Iphicrates had 8000 men in Thrace at one stage, but we cannot be sure if this was when he was in Kotys service or when he was campaigning in the same area on Athens behalf. Many of Iphicrates victories were gained using peltasts as the main arm, but what Kotys needed was hoplites, and these probably formed the mainstay of his mercenary force. Unfortunately, when the Macedonians invaded, the Thracians had no such infantry capable of defeating the Macedonian phalanx.

QuoteOne of the most powerful of these appeared in 400, when Seuthes II hired the 6,000 or so survivors of Xenophons army to get his own domain on the Black sea coast. They were mainly hoplites, but included nearly 1,000 peltasts, javelinmen, and slingers, and 50 cavalry. Xenophon says simply that Seuthes had an army larger than the Greek army; and that it tripled in size as the news of its success spread. This could mean that Seuthes army grew to a strength of around 20,000 men, including the Greeks. The Thracian contribution to this army would have been around 4,000 Odrysian light cavalry, 500 heavy cavalry, 500 archers and slingers, 7,000 peltasts, and 2,000 javelin-armed lighter infantry.

QuoteMountain tribes were more warlike and favoured infantry, while those from the plains favoured cavalry. The Odrysai fielded 8,000 horse (28%) and 20,000 foot against Lysimachos. A detachment of Odrysians sent by Seuthes to aid the Spartans in Bithynia in 398 was composed of 200 cavalry (40%) and 300 peltasts. Thucydides says that the Getai and their neighbours by the Danube were all mounted archers in the Skythian style. However, Alexander faced a Getic army of 4000 horse and 10,000 foot, or about 28% cavalry. Seuthes hired 2,000 Getic light troops for use against the Athenians in the Thracian Chersonese, which shows they may have been a regular component of Odrysian armies. So an Odrysian royal army might contain between 25% and 40% cavalry, while the army of a single tribe or group of hill tribes might have much less.

QuoteHorse riding epitomised the Thracians. Euripides and Homer called the Thracians a race of horsemen, and Thrace, the land of the Thracian horsemen. This description seems justified, as even though the cavalry only made up a small proportion of their army, they were quite numerous. For instance, although Sitalkes army was only one-third cavalry, this represented about 50,000 men. The majority of these were Odrysians and Getai. Thus the Odrysians alone could outnumber all the fifth-century Greek cities and other tribal kingdoms collectively in cavalry forces. However, Macedonian heavy cavalry operated against them with impunity when Sitalkes invaded Macedonia. The Macedonians... made cavalry attacks on the Thracian army when they saw their opportunity. Whenever they did so, being excellent horsemen and armed with breastplates, no one could stand up to them... This happened again during the battle of Lyginus between Alexander and the Triballi. The cavalry were chiefly unarmoured javelin-armed skirmishers, with relatively few armoured cavalry forming a bodyguard for the king. This might explain why Sitalkes had no troops able to stand up to the heavy Macedonian cavalry. Against the Greeks, though, they seem to have had more success, with several Greek armies being wiped out during colonisation attempts. Perhaps the best evidence for the success of Thracian cavalry is the way that the mainland Greeks took up Thracian cavalry dress, and horsemanship. Athenian riders wearing Thracian boots and/or Thracian headdress can be seen on the Parthenon frieze, and wearing Thracian cloaks on Athenian pottery.

QuoteThe fourth century saw the start of many changes in cavalry dress and equipment. The distinctive Thracian dress was discarded, additional armour of new types was worn, shields and saddles came into use, and light infantry was trained to support cavalry. Light cavalry was now likely to have the basic protection of helmet and shield, while heavy cavalry took to wearing iron helmets and composite corselets. From the late fourth century onwards, Odrysian cavalry operated mostly as allied or subject troops. In particular, Thracian troops were critical to the success of Alexander the Great. They formed about one fifth of his army (25% of the infantry and 20% of the cavalry to begin with) and took part in almost all his battles. Of the forces that crossed to Asia, there were 7,000 Odrysians, Triballi and Illyrians plus 1,000 archers and Agrianians (a Paionian tribe) out of a total of 32,000 foot soldiers. There were also 900 Thracian and Paeonian scouts, out a total of 4,500 cavalry. A further 500 Thracian cavalry joined Alexanders army while it was at Memphis. A body of Odrysian horse (probably heavy cavalry), commanded by Sitalkes, an Odrysian prince, was likewise present. 600 Thracian cavalry and 3,500 Trallians joined Alexander after he left Babylon.

QuoteAt the battle of the Granicus in 334, Alexander deployed the Thracians on his left flank, but they were not engaged during the battle. Thracian cavalry took part in Alexanders rapid march to Miletus, and Thracian javelinmen screened the Macedonian left flank in battle against the Pisidians. Before the Battle of Issos (333) we find Alexander using the light armed Thracians to reconnoitre the mountainous surroundings of the Cilician Gates. At the subsequent battle the Thracians were initially in the van of the army, then they were again posted on the left wing, brigaded with Cretan archers. They were also on the left wing at Gaugamela (331), when the savage Thracians (cavalry and infantry) helped beat off a sustained attack by superior numbers of Persian cavalry. However, the Thracian infantry had mixed success defending the baggage against the Indian cavalry. Although many other troops were allowed to return home before or during the march to India, the Thracians stayed on. 3,000 infantry and 500 horsemen would be left as a garrison on the Indus river near the present day city of Rawalpindi. At the battle of the Hydaspes (326), the Thracian light infantry attacked the Indian elephants with copides (curved swords or rhomphaias). The Agrianians in particular were given many critical missions.

QuoteMany other battles in the struggle for Alexanders empire involved Thracian troops. Eumenes deployed Thracians on his left flank at the battle of the Hellespont in 321. At Paraitakene (317), 500 Thracian cavalry fought on one side and 1000 cavalry fought on the other (possibly colonist Thracians verses native Thracians the native Thracians won). Thracian cavalry next rose to prominence in the wars with the Romans. In 171 Perseus was joined by Kotys, king of the Odrysai with 1,000 picked cavalry and about 1,000 infantry. Perseus already had 3,000 free Thracians under their own commander in his forces. These fought like wild beasts who had long been kept caged at the Kallinikos skirmish that year, defeating the Roman allied cavalry. They returned from battle singing, with severed heads as trophies. Their performance at the Battle of Pydna (168) was less remarkable, they are only mentioned when running away, Thracian cavalry are recorded switching sides in 109, when two mercenary squadrons were bribed to let Jugurtha into a Roman camp. The last significant instance of the use of Thracian horsemen seems to be in 71 - while Lucullus was campaigning in Pontus, he used Thracian cavalry to successfully charge Armenian cataphracts in the flank.

-

2

2

-

-

Diodorus Siculus, 15.44.3 : It will not be out of place to set forth what I have learned about the remarkable character of Iphicrates. For he is reported to have possessed shrewdness in command and to have enjoyed an exceptional natural genius for every kind of useful invention. Hence we are told, after he had acquired his long experience of military operations in the Persian War, he devised many improvements in the tools of war, devoting himself especially to the matter of arms. For instance, the Greeks were using shields which were large and consequently difficult to handle; these he discarded and made small oval ones (peltas summetrous) of moderate size, thus successfully achieving both objects, to furnish the body with adequate cover and to enable the user of the small shield, on account of its lightness, to be completely free in his movements. After a trial of the new shield its easy manipulation secured its adoption, and the infantry who had formerly been called "hoplites" because of their heavy shield, then had their name changed to "peltasts" from the light pelta they carried. As regards spear and sword, he made changes in the contrary direction: namely, he increased the length of the spears by half, and made the swords almost twice as long. The actual use of these arms confirmed the initial test and from the success of the experiment won great fame for the inventive genius of the general. He made soldiers' boots that were easy to untie and light and they continue to this day to be called "iphicratids" after him. He also introduced many other useful improvements into warfare, but it would be tedious to write about them. So the Persian expedition against Egypt, for all its huge preparations, disappointed expectations and proved a failure in the end.

Cornelius Nepos, Life of Iphicrates: Iphicrates of Athens has become renowned, not so much for the greatness of his exploits, as for his knowledge of military tactics; for he was such a leader, that he was not only comparable to the first commanders of his own time, but no one even of the older generals could be set above him. He was much engaged in the field; he often had. the command of armies; he never miscarried in an undertaking by his own fault; he was always eminent for invention, and such was his excellence in it, that he not only introduced much that was new into the military art, but made many improvements in what existed before. He altered the arms of the infantry; for whereas, before he became a commander, they used very large shields, short spears, and small swords, he, on the contrary, introduced the pelta instead of the parma (from which the infantry were afterwards called peltastae), that they might be more active in movements and encounters; he doubled the length of the spear, and made the swords also longer. He likewise changed the character of their cuirasses, and gave them linen ones instead of those of metal; a change by which he rendered the soldiers more active; for, diminishing the weight, he provided what would equally protect the body, and be light.

-

1

1

-

-

-

-

-

On 02/02/2023 at 1:53 AM, TheScroll said:

What game is this from? The details are jaw-dropping.

-

-

53 minutes ago, Stan` said:

DO you have a link to the UE4 video?

I posted it above already:

-

2

2

-

-

1 minute ago, Lion.Kanzen said:

Ukra-nazis ,lol.

Sure...

-

1

1

-

-

On 25/11/2022 at 6:22 AM, Obskiuras said:

Those are generally called "stone babas", they are not necessarily Scythians:

http://www.encyclopediao@#$%raine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages\S\T\StonebabaIT.htm

=> https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

9 minutes ago, Stan` said:

Thanks @Genava55 that was pretty interesting. I still wonder how they had "millions of polygons" and still a not so good rendering.

Having a model with millions of faces is easy. I am pretty sure the issue was to have an efficient tool and a better computer to render it into a video.

The difference between the video of 2007-2010 and the video of 2021 rendered on Unreal Engine 4 is striking and I am pretty sure the original models were mostly the same.

34 minutes ago, Stan` said:Maybe someday we'll redo the gauls to be a more refined society with roof tiles and painted roofs. The contrast between civiisation and bashing animal skulls on rock and then displaying them is still crazy to me

Yes it's crazy but as they point out, it makes sense. It is practiced in Africa and Asia to display the status of the community and keep an account of sacrifices.

It is shocking for a modern man only. Sacrificing an animal is pretty difficult for us:

Futhermore, the other civilizations weren't that much elevated on the sacrifice topic.

Romans considered themselves as civilized and criticized deeply other peoples, but as Plutarch reported:

"What is the reason for the following facts: on learning that the barbarians named Bletonesioi had offered a human sacrifice to the gods, they sent a mission to punish their leaders – and nevertheless, as it appeared that they had only done to apply their laws, they were left free, not without forbidding them this practice in the future. But then how is it that the same Romans, a few years earlier, buried alive, in the square called Ox-Market, two men and two women, one Greek, the other Gallic? It seems absurd of them to have indulged in such practices themselves, while blaming the barbarians for their unholy behavior."

Romans still practiced human sacrifices in secret until 90 BC. One of such sacrifice was to burn alive a man...

-

1

1

-

-

On 21/09/2021 at 10:52 PM, Genava55 said:

A new 3d modelling of Corent, an oppidum with a sanctuary.

@Stan` Je sais pas si ça peut t'intéresser, mais il y a une ancienne conférence de 2010 qui a été publiée sur youtube à propos de Corent, de l'interprétation du site et de sa reconstitution en 3D:

-

1

1

-

-

-

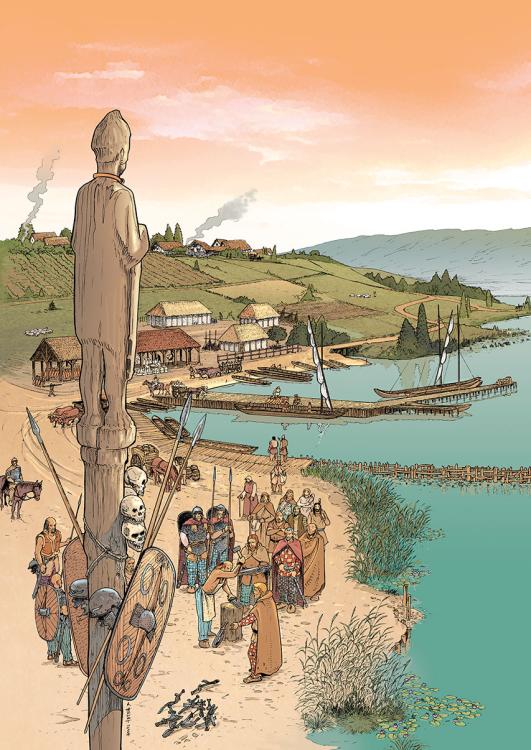

Settlement of Le Cailar, nearby Massalia. Territory of the Saluvii/Salyes.

-

1

1

-

-

34 minutes ago, Ultimate Aurelian said:

Are those two different versions or is the back of the building made of a different material than the front?

It is simply incomplete on the back (which is pretty useless).

-

1

1

-

-

5 minutes ago, Lion.Kanzen said:

There is not much that can be done, other than making anti missile formations(shield wall). Adding missile infantry in rear and defenses.

Yes indeed. Infantrymen should have a better protection by being in a battle-formation.

Ideally, infantrymen and light infantry should have also the same speed when not in a formation. I don't understand why some peltasts with shields and helmets should be faster than unarmoured spearmen for example. Historically, heavy infantrymen moved very fast when they broke out of their formation. It is staying in a cohesive formation that make them slower.

By giving more importance to the heavy infantry and to formation, it gives more incentive to micro-manage them.

Cavalry should have a bonus against infantry not in formation.

-

3

3

-

.thumb.jpg.b21ca1d0c15fb56b42c39b25a0a40815.jpg)

Romans military image references

in Tutorials, references and art help

Posted