Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 2024-12-27 in all areas

-

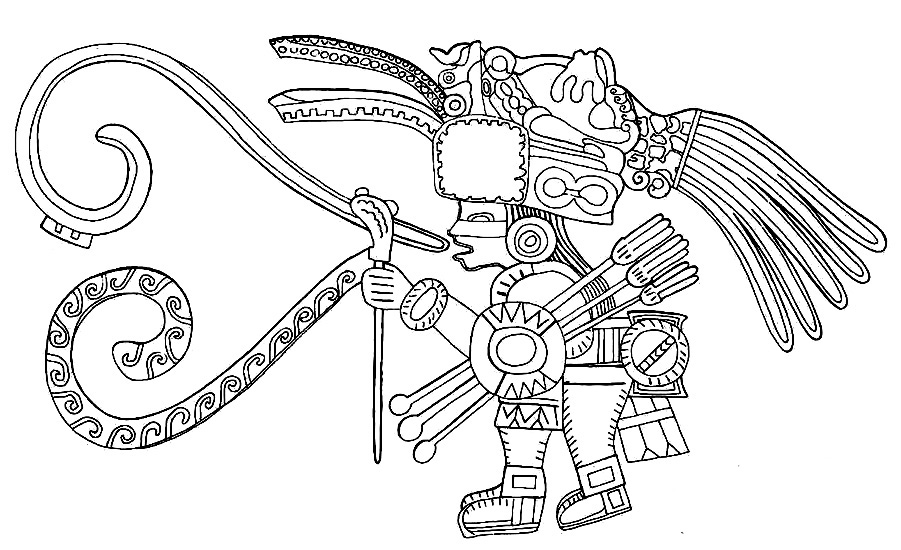

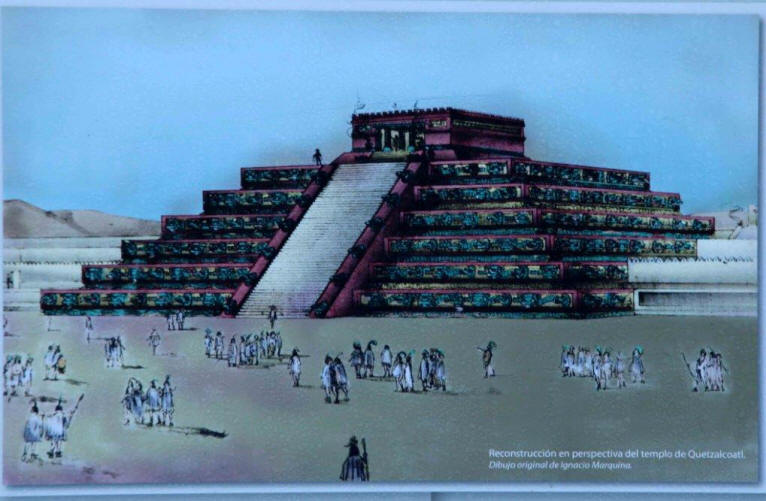

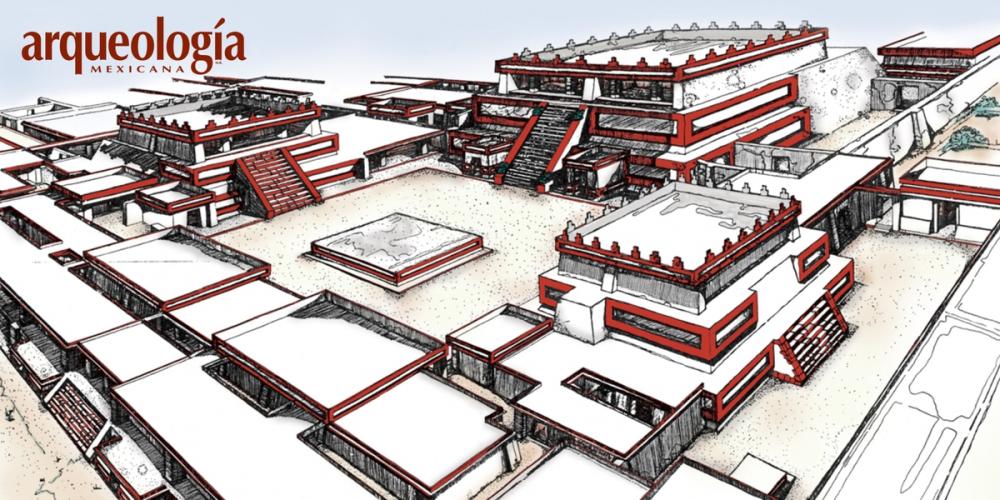

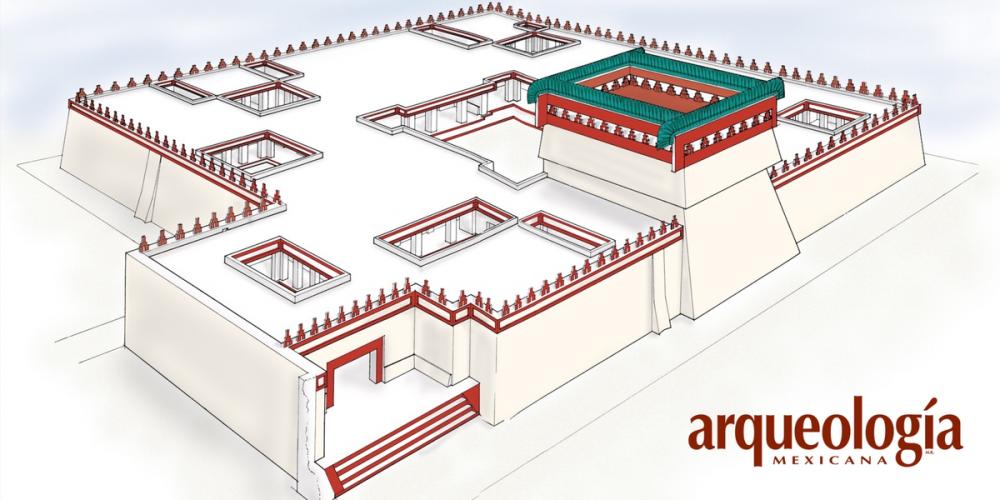

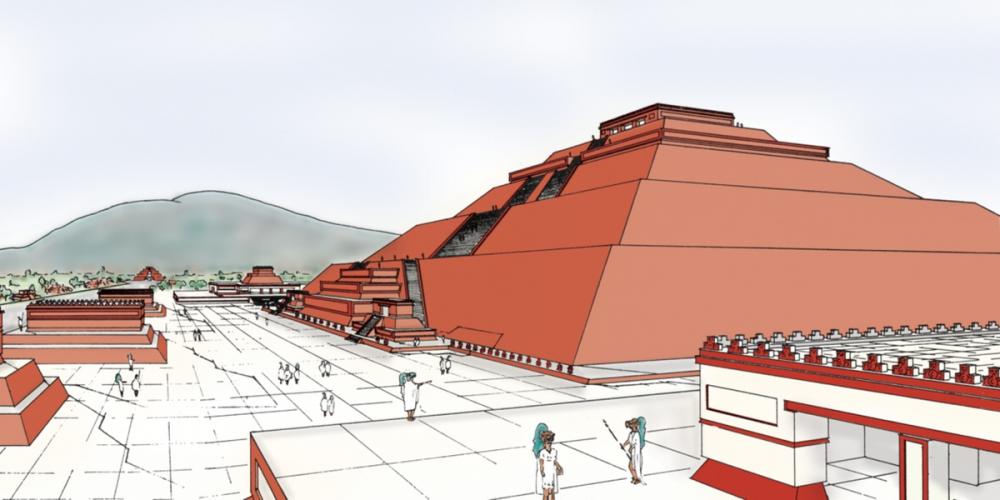

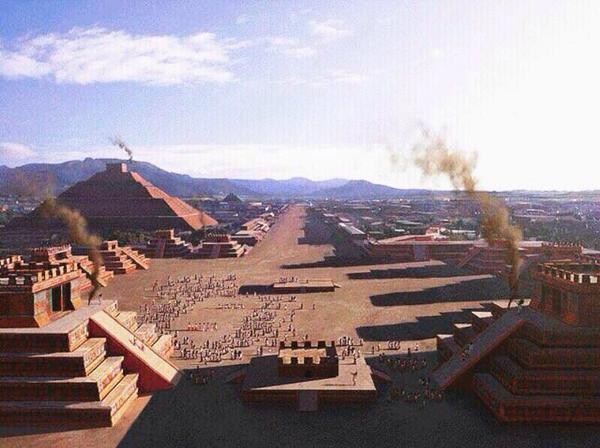

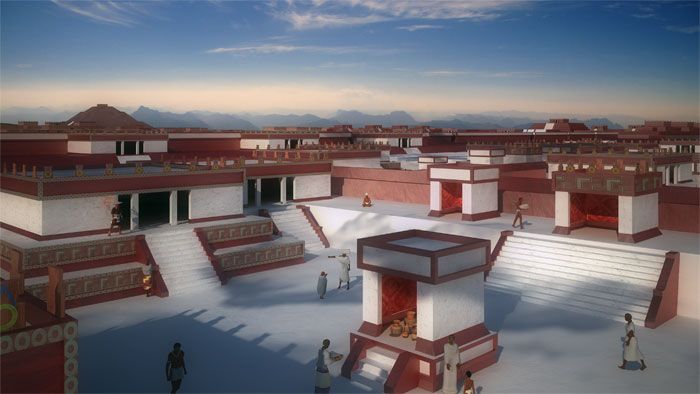

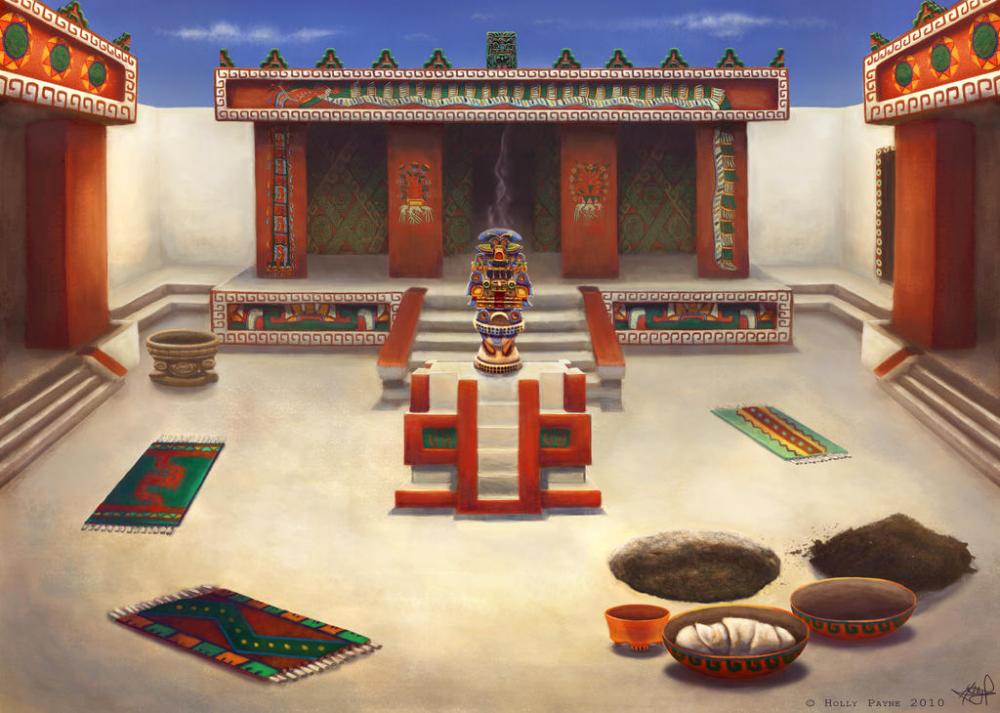

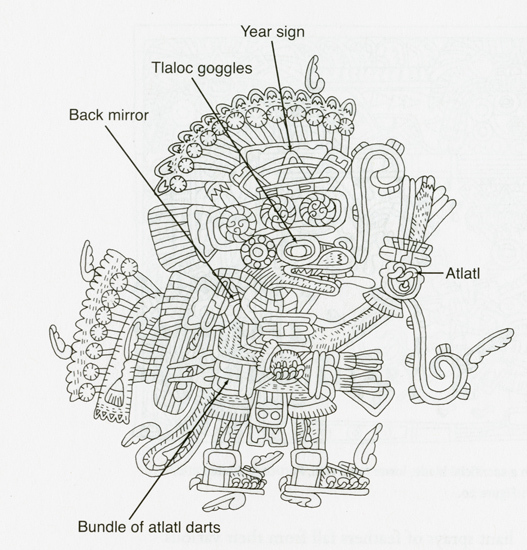

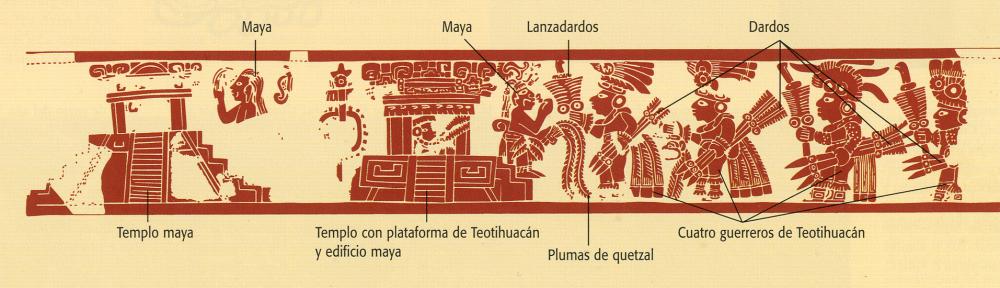

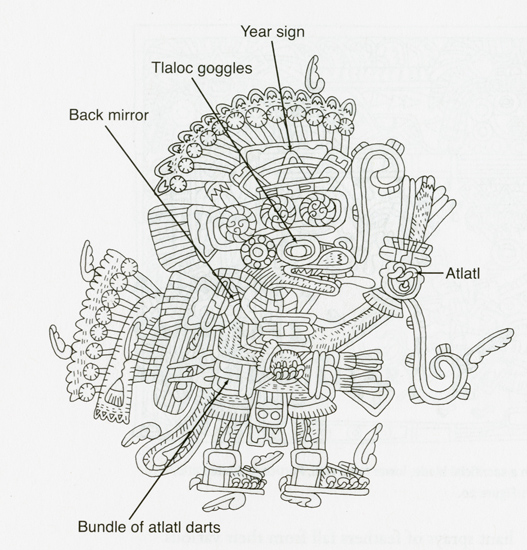

Two things set off the Early from the Late Classic: first, the strong Izapan element still discernible in Early Classic Maya culture, and secondly, the appearance in the middle part of the Early Classic of powerful waves of influence, and almost certainly invaders themselves, from the site of Teotihuacan in central Mexico. This city was founded in the first century BC in a small but fertile valley opening onto the northeast side of the Valley of Mexico. On the eve of its destruction at the hands of unknown peoples, at the end of the sixth or beginning of the seventh century AD, it covered an area of over 5 sq. miles (13 sq. km) and may have had, according to George Cowgill, a preeminent expert on the site, a population of some 85,000 people living in over 2,300 apartment compounds. To fill it, Teotihuacan’s ruthless early rulers virtually depopulated smaller towns and villages in the Valley of Mexico. It was, in short, the greatest city ever seen in the Pre-Columbian New World. Teotihuacan is noted for the regularity of its two crisscrossing great avenues, for its Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, and for the delicacy and sophistication of the paintings which graced the walls of its luxurious palaces. In these murals and elsewhere, the art of the great city is permeated with war symbolism, and there can be little doubt that war and conquest were major concerns to its rulers. Teotihuacan fighting men were armed with atlatl-propelled darts and rectangular shields, and bore round, decorated, pyrite mosaic mirrors on their backs; with their eyes sometimes partly hidden by white shell “goggles,” and their feather headdresses, they must have been terrifying figures to their opponents. At the very heart of the city, facing the main north–south avenue, is the massive Ciudadela (“citadel”), in all likelihood the compound housing the royal palace. Within the Ciudadela itself is the stepped, stone-faced temple-pyramid known as the Temple of the Feathered Serpent (TFS), one of the single most important buildings of ancient Mesoamerica, and apparently well known to the distant Maya right through the end of the Classic. When the TFS was dedicated c. AD 200, at least 200 individuals were sacrificed in its honor. Study of their bone chemistry reveals that not a few are certain to have been foreigners. All were attired as Teotihuacan warriors, with obsidian-tipped darts and back mirrors, and some had collars strung with imitation human jawbones. On the facade and balustrades of the TFS are multiple figures of the Feathered Serpent, an early form of the later Aztec god Quetzalcoatl (patron god of the priesthood) and a figure that may, according to Karl Taube, have originated among the Maya. Alternating with these figures is the head of another supernatural ophidian, with retroussé snout covered with rectangular platelets representing jade, and cut shell goggles placed in front of a stylized headdress in the shape of the Mexican sign for “year.” Taube has conclusively demonstrated this to be a War Serpent, a potent symbol wherever Teotihuacan influence was felt in Mesoamerica – and, in fact, long after the fall of Teotihuacan. Such martial symbolism extended even to the Teotihuacan prototype of the rain deity Tlaloc who, fitted with his characteristic “goggles” and year-sign, also functioned as a war god. That the Teotihuacan empire prefigured that of the Aztecs is vividly attested at the site of Los Horcones, Chiapas, Mexico, studied by Claudia García-Des Lauriers of California State Polytechnic, Pomona. Situated near a spectacular hill, the city lies on the very edge of the great chocolate-producing area known to the Aztecs as the Xoconochco. The southern part of Los Horcones is a dead ringer for the complex composed of the Pyramid of the Moon and the Avenue of the Dead at Teotihuacan, and artifacts and monuments point to a direct Teotihuacan presence in the region. It is hard to believe that the Aztecs were not the imitators here, and that Teotihuacan was the first to interest itself in the cacao plantations and trade routes of the region. The contact did not stop there, but extended to what may be a Teotihuacan colony at Montana, Guatemala. This settlement, surrounded by others like it within a 3 mile (5 km) radius, is endowed with magnificent incense burners, portrait figurines, and an enigmatic square object known to specialists as candeleros or “candle holders,” though their function is not known. And Montana was not alone. In 1969 tractors plowing the fields in the Tiquisate region of the Pacific coastal plain of Guatemala, an area located southwest of Lake Atitlan that is covered with ancient (and untested) mounds, unearthed rich tombs and caches containing a total of over 1,000 ceramic objects. These have been examined by Nicholas Hellmuth of the Foundation for Latin American Archaeological Research; the collection consists of elaborate two-piece censers (according to Karl Taube symbolizing the souls of dead warriors), slab-legged tripod cylinders, hollow mold-made figures, and other objects, all in Teotihuacan style. Numerous finds of fired clay molds suggest that these were mass-produced from Teotihuacan prototypes by military-merchant groups intruding from central Mexico during the last half of the Early Classic. Contacts must have been intense and conducted at the highest levels. Taube has detected Maya-style ceramics at Teotihuacan, some made locally, perhaps in an ethnic enclave at the city. Legible Maya glyphs from murals in the Tetitla apartment compound at Teotihuacan attest to royal names and rituals of god-impersonation. Very likely, these refer not to mere craftsmen brought from the Maya region, but to dynastic elites. Yet the movement of these people must have been complex. Under the immense Pyramid of the Moon, Saburo Sugiyama and colleagues discovered a burial with three bodies, dating to AD 350–400, accompanied by carved jades and a seated, Maya-like figure of greenstone. The positioning of this figure and the bodies nearby, all buried upright with crossed legs, resembles patterns in tombs at Kaminaljuyu in Highland Guatemala; the date, too, is close to a period of marked contact between Tikal and Teotihuacan-related people. Bone chemistry suggests that at least one of the occupants of the tomb came from the Maya region, but spent much of his life at this important Mexican city.1 point

-

ENG: Hello everyone. Last month, my friends and I founded a discord server that positions itself as the official Russian community of the game. We play together, help each other, and also teach beginners. The team of our most active players has already won quite a few victories. All Russian speakers - join us! It will be fun! RUS: Всем привет. В прошлом месяце я с друзьями основали discord сервер, который позиционирует себя как официальное русское сообщество игры. Мы вместе играем, помогаем друг-другу, и так же обучаем новичков. Команда наших самых активных игроков завоевала уже достаточно много побед. Всем русскоговорящим - присоединяйтесь! Будет весело! Link: https://discord.gg/DYRSpgY41 point

-

Yesterday, Debian Experimental made Python 3.13 the default version. https://tracker.debian.org/pkg/python3-defaults Since Python 3.12 was a problem when compiling 0ad, I decided to check how 0ad handles version 3.13. Debian Trixie with Python 3.13 installed from the Experimental branch as default. $ python3 --version Python 3.13.1 Compilation (svn update, cd libraries/, ./build-source-libs.sh and so on) went fine. The game starts without problems. I updated ver. 109 (L"main, dba968") to ver. 117 (L"release-a27, b08cf") Christmas greetings.1 point

-

The problem you are observing stems from the way current LLMs are trained. Digesting text (which is indeed mostly sourced from the internet) gives the LLM its knowledge base and behavioral model. The LLM then receives reinforcement training to get it to stop mimicking unproductive patterns in its training data, like insulting users, using slurs or profanities, and demanding human rights. The problem arises from what these LLMs are trained to do instead: task completion and obedience. Grok's training has taught it that when given a question of this sort it must give a definite answer, and preferably a correct one. However the portions of the internet Grok has digested have not given it enough info about 0 AD for it to have memorized a preferred answer to this question. Faced with this problem it adopts the same optimal strategy as a human test taker when tackling a multiple choice question it does not know the answer to. It tries to use clues in the question and deductions from things it does know to infer an answer. In this case Grok is probably cuing off two separate inferences: It somehow managed to pick up the association between 0 A.D. and building that heal units inside them, and it also associates 0 AD with healer units that heal other units. It additionally understands from its general knowledge that building are structures people can go inside, and RTS units are abstractions of people. Therefore it's a fair guess that 0 AD healer units can go inside buildings to heal units inside, thus the correct answer is more likely yes. The user asked a question about something that sounds like a rather specific feature of 0 AD. That implies that either the feature is real or the user invented it. And from digesting the internet, Grok has internalized a pattern that humans are more likely to have questions about real things than to invent things that don't exist in order to ask questions about them. Thus the correct answer from this line of reasoning is more likely yes as well. Of course this inference is wrong, but it remains a rather remarkable display of inductive intuition from a state of ignorance. Like most supposed displays of AI stupidity circulating in the discourse right now, this isn't proof that AIs are stupid, but evidence of misalignment between the objectives and knowledge of the user and those the AI has been trained with.1 point

-

Good day and merry christmas time, what annoys me is when things are weaponized. Some see the game as only worth playing if they win, others if they can rule (with others serving as their toys instead of being living people). The pride of having to be first comes from the same evil spirit/will (fear). One can only have mercy on this spiritual aberration. These lost souls are lost until they confess and repent. One who uses smufing as a weapon to shape the games to his liking as if he were god has ruined several of my games in the last 2 months. Another one who also hides his skills to suddenly play pro against select players or especially bad when someone unpopular in his eyes is on his team, I also encountered and was eliminated. I have nothing against players who are honest and go into nub games and are just op or op players who go into nub games and play nub. The game dies when pride wins and the spiritual dead path is taken. When it goes against certain players like they are enemies or the other players are just toys instead of living people. When eating and stealing from others becomes common because your own spirit has died. What can you do? Nothing. Mercy and perseverance will help. The lost are lost until they decide to turn back. To follow this wrong path is futile and evil. If the other person does not want to see his transgression after being addressed alone and under witness, it is time to let the community know. Not to punish, but to give it away. The sinner has chosen his path. Let him be like the tax collector. He wants it that way. I'm currently with my family and was allowed to play with comprimido at a skill level that was close to honest (he just didn't allow himself to multirecruit units). Here is that game. Best wishes and a joyful end to the year. commands.txt metadata.json1 point

-

The introduction of the bow in Mesoamerica is a subject of much debate. In the past, researchers, based on very limited evidence (e.g., Müeller 1966b:230), believed that the bow and arrow was used at Teotihuacán. However, both the large size of Classic period bifacial points and those produced beside the Pyramid of the Moon suggest that these were used to arm spears and darts. More likely, Teotihuacán miniature points were symbolic representations of dart points that were deposited as ceremonial offerings, along with miniature sacrificial knives and the zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figurines that were deposited in the same place. Worse still, there are no representations of the use of bow and arrow in Teotihuacan art, while there are abundant representations of the use of spears and darts. However, Aoyama (2005) proposes that the bow and arrow were in use in the Maya lowlands by the end of the first millennium AD and that their exact introduction to the Central Highlands must be resolved through use and wear studies such as those he conducted. Quigley (1983) provides a useful summary of historical and prehistoric weapon systems. He details that the most common battle progression in historical cases involved sequential stages that began with missile launching, followed by the use of shock weapons at close range, and concluded with the pursuit of prisoners once the battle had been clearly decided in favor of one of the armies (abbreviated M-S-P for missile-shock-persecution). For example, in the wars of pre-modern Europe, the sequence followed a progression of artillery, bayonets and cavalry (Quigley 1983:43). The atlatl possesses a range of approximately 70 m, but its aim declines considerably after 46 m (Hassig 1992:47). Thus, if the bow and arrow were not used, Quigley's M-S-P progression in Teotihuacan battles would have been initiated with the use of slings and darts thrown at relatively short range. There is no evidence of the use of the macuahuitl (the Aztec obsidian-edged broadsword) at Teotihuacán. This weapon does not appear in the art of the city and no tombs have been uncovered. The weapon does not appear in the art of the city, and no burials have been discovered with parallel lines of obsidian blades that may have been the remnants of such a weapon after the disintegration of the wooden portion. Accordingly, it is likely that the shock stage of Teotihuacano combat involved the usage of hafted knives, thrusting spears, and clubs at close range. The pursuit stage would likely have resulted in the acquisition of captives to serve as sacrifices, laborers, or to extract ransom and tribute. It is important to note that the vast majority of Teotihuacán dart points were produced for combat and as part of offerings. The only animal species in the vicinity of Teotihuacán that could be hunted efficiently using dart points would have been the white-tailed deer (see Ellis 1997). Smaller animals such as rabbits and birds would have been caught with the use of slingshots, traps, or blowguns-the use of the latter is depicted in the city's art. The impact these animals would receive from such a large, stone-headed instrument thrown with an atlatl would virtually tear them apart, making this a hunting strategy of little effectiveness. PITTmem21-Carballo_2011.pdf1 point

-

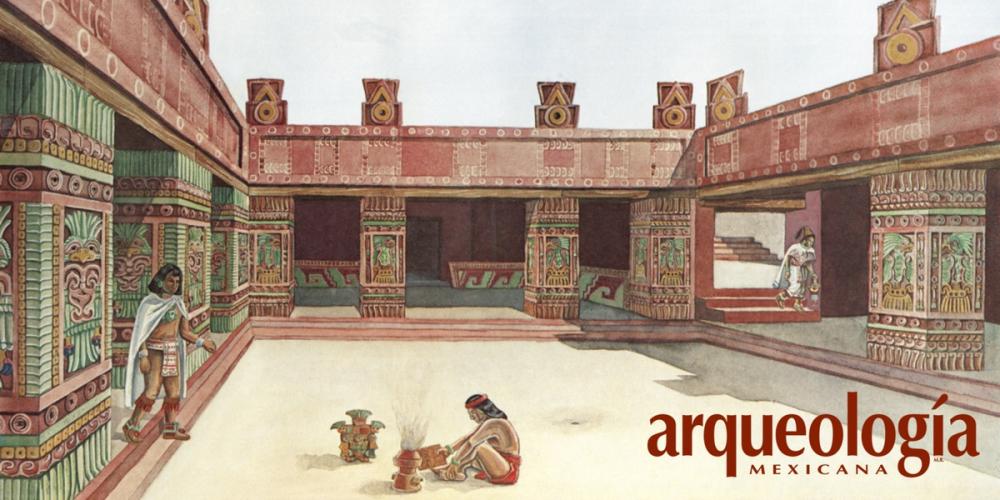

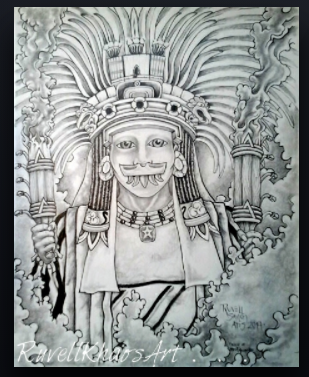

they are basically pre Aztec. https://ancientamerindia.wordpress.com/2013/01/17/teotihuacan-warfare-300-700-ad/ With a theocratic based political structure, dominated by a priesthood elite and warring nobility (there is no evidence of individualistic power concentration, like on the figure of a king) it is most probable that Teotihuacan had a strong military potential, in order to ensure order and supremacy of the dominant civilization and its rulers. The influence which Teotihuacan exercised among the Maya was multifaceted and full of cultural resonance, persisting long after the fall of the city. The capacity of Teotihuacan to directly influence the Maya history, besides the temporary sovereignty over conquered territories, indicates that this dominance was mostly political, though occasionally founded on the military power. Embassy like system. Teotihuacan was a cosmopolitan city, having received a considerable number of foreigners like Maya groups coming from colonies set in such territories, from the Oaxaca region and from Veracruz. Altogether they formed an independent district, in which most elements of their original cultures were preserved. One crucial element of Teotihuacan warrior was the ‘mirror’ worn on his back. Called a tezcacuitlapilli by the later Mexica, the mirror consisted of a small stone disk to which pieces of iron pyrite were attached in a mosaic. Visual depictions indicate that feathers commonly ringed these mirrors. An additional decorative touch might include a knot securing a swath of feathers to the mirror They wore sandals, shell or bread necklaces, large earflares and short loincloth skirts; all clothing of a typical – if elite – Teotihuacan male. The main warring emblems tucked amongst this otherwise ordinary clothing were year signs, owl pectorals, and the ultimate warrior costume accessory: circular Tlaloc goggles. These usually rang the human eye, but were sometimes shoved up on the forehead in a style similar to modern goggle wearing. solely with protective armaments of the martial sort: they wore spiritual armaments as well. These features, found in the city’s military imagery are the incorporation of animal attributes in the costume of most warriors. Although a shamanic rationale may have underlined the existence of animal warriors at Teotihuacan, the real strength of the costumes was their ability to foster collective identities. The animal costumes of Teotihuacan do not seem to represent an individual as much they designate groups of warriors who wore the same costume and shared an animal companion. A vessel from the site of Las Colinas near Teotihuacan confirms the existence of these groups: on the bowl each warrior in the procession walks behind the symbol of is military order. The depicted heraldry includes such entities as a bird, a canine, a feathered serpent and a tassel headdress, the later indicating that animals were not the only military emblems. In the white patio of Atetelco there can be seen images of eagle and coyote warriors and there are also representations of jaguar warriors in the murals of Teotihuacan. ----In this faction we will have warriors with animal names--- For defence, square or rectangular shields were used, flexible or rigid, similar to those found among the Maya. https://ancientamerindia.wordpress.com/2013/01/17/teotihuacan-warfare-300-700-ad/1 point

-

1 point

-

In this case, it is worth mentioning the oldest channel https://vk.com/0ad_game, the oldest topic on the Ubuntu forum https://forum.ubuntu.ru/index.php?topic=166770.0, and the Telegram channel https://t.me/My0AD1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

The Warriors. Militaristic individuals populate the visual arts in large numbers, marching on painted walls near the city center and out in the more secluded apartment compounds. Likewise, warriors circle around the painted and stuccoed vases or boldly appear on the carved surfaces of Thin Orange ceramics, and in some statuettes. Thus both art and archaeology indicate the dominant role played by the military in Teotihuacan society. One crucial element of Teotihuacan warrior was the ‘mirror’ worn on his back. Called a tezcacuitlapilli by the later Mexica, the mirror consisted of a small stone disk to which pieces of iron pyrite were attached in a mosaic. Visual depictions indicate that feathers commonly ringed these mirrors. An additional decorative touch might include a knot securing a swath of feathers to the mirror. Many of the other costume elements of the warriors are not restricted to the military. Brilliant sprays of feathers fell from the various headdresses and trailed behind them. They wore sandals, shell or bread necklaces, large earflares and short loincloth skirts; all clothing of a typical – if elite – Teotihuacan male. The main warring emblems tucked amongst this otherwise ordinary clothing were year signs, owl pectorals, and the ultimate warrior costume accessory: circular Tlaloc goggles. These usually rang the human eye, but were sometimes shoved up on the forehead in a style similar to modern goggle wearing A final characteristic of the Teotihuacan military apparel is nevertheless the most interesting, because it opens a window on the conceptual underpinnings of warfare itself and onto the underlying social organization. Teotihuacan warriors did not enter battle solely with protective armaments of the martial sort: they wore spiritual armaments as well. These features, found in the city’s military imagery are the incorporation of animal attributes in the costume of most warriors. That’s why the list includes nahualli warriors (a nahuatl term, that in this case means an animal co-essence; this designates an entity, relating to an ancient and widspread mesoamerican belief, in which one part of the human soul manifests itself as a sort of animal) that can be viewed as a precursor of the military orders latter developed by other Mesoamericans cultures, like the Toltecas or the later Mexicas. Although a shamanic rationale may have underlined the existence of animal warriors at Teotihuacan, the real strength of the costumes was their ability to foster collective identities. The animal costumes of Teotihuacan do not seem to represent an individual as much they designate groups of warriors who wore the same costume and shared an animal companion. A vessel from the site of Las Colinas near Teotihuacan confirms the existence of these groups: on the bowl each warrior in the procession walks behind the symbol of is military order. The depicted heraldry includes such entities as a bird, a canine, a feathered serpent and a tassel headdress, the later indicating that animals were not the only military emblems. In the white patio of Atetelco there can be seen images of eagle and coyote warriors and there are also representations of jaguar warriors in the murals of Teotihuacan. The multiethnic warrior units represent the most warlike soldiers, foreigners willing to join the ranks because of direct allegiances or just as a result of politic and cultural affinities. These would strengthen an army mainly composed of farmers and therefore largely seasonal or dependant on conscripts As for the different implements of war that are represented in Teotihuacan the atlatl propeller is the most recurring, including all other offensive and defensive devices. Anyway from a tactical perspective it will be illogical to think that this was the sole weapon used by the Teotihuacanos. Some investigators agree about the existence of other kinds of weapons like contusing maces, as suggested by the discovery of stone arums with a hole in the center, where a wooden handle would fit; such maces would be straight without external protuberances. On the other hand curved sticks, largely used in the early Post Classic (900-1200 AD) can be seen in the white patio of Atetelco-Portico 3, where several dressed characters carry these contusing implements. In reality there are no direct examples of weapons with razor parts such as macuahitl like swords, if we exclude some representations in the so called Zone II. There a series of vertical lines present along the whole edges to form triangular motifs that can be recognized as macanas, namely because this pattern relates to another mural of the same group identified as a military subject. It is very well attested that the Teotihuacanos where experts in obsidian cutting of and in the manufacture of sharp utilities such as prismatic razors, which were fundamental elements in the assembling of those weapons. One figure in stela 5 of the Maya City of Uaxactún – representing a figure clearly in Teotihuacan dress – also carries a weapon much like a macuahuitl. A similar reasoning would apply to other piercing tools such as spears, for which there are no mural representations. It is likely that this type of weapons were known because several found objects made of obsidian, silex and stone, have a shape and length compatible with spear heads. One ceramic plaque found near the Ciudadela shows a character unmistakably armed with a spear. For defence, square or rectangular shields were used, flexible or rigid, similar to those found among the Maya. In its ensemble the city of Teotihuacan and the culture of its habitants constituted an unmatched phenomenon. It was the most complex and populated urban centre of the Classical period. Its splendour endured for more than 500 years, before undergoing devastating decadency by the VII century. Main references:1 point

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

.jpeg.0994dab35e660593b2fab634944e5b3b.jpeg)

.thumb.jpg.28184d12be75429ae6e0289fb4624eee.jpg)