-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

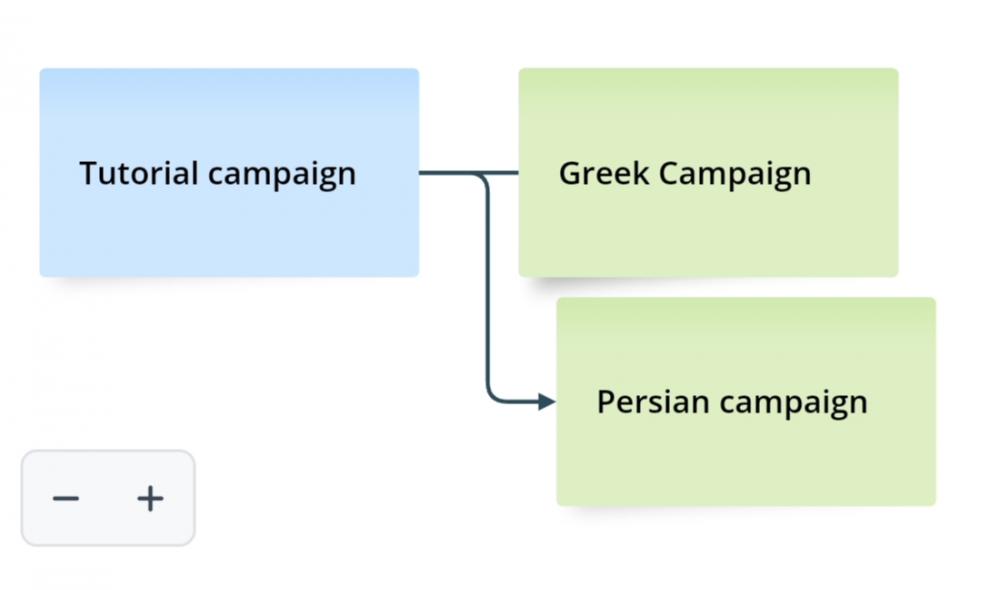

After the tutorial.. I must make a conceptual map so that you understand me better. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

We can also make a sub version, that is, a modified version for the campaign. -

This? It's just a video from someone who uploaded it for some reason. This user had never seen it before. Indeed, there is nothing special, I hope he uploads better videos.

-

It has an emoji and it won't let me paste it in the forum https://youtu.be/5cK0ltZA4Oc?si=yiCw-Pq9PdZ9JMvN

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Others RTS - Discuss / Analysis

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Introductions & Off-Topic Discussion

I definitely want to try it. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

gameplays Age of Empires 2 stuff

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Introductions & Off-Topic Discussion

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

We use the faction that most closely resembles it. We can add to them campaign units. (available only in the atlas editor). That happens in all RTS: special campaign units. https://empireearth.fandom.com/wiki/Scenario_editor-only_units -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

The initial campaign is Greek, the Greco-Persian Wars. I don't know whether to make a single story for the Greek factions(classical) or separate them. The second is the Persian campaign. I imagine a screen menu and a character being selected. It would be no different than how they appear in Total War Attila. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

This is a tutorial campaign, you can skip it. It is a series of learning scenarios. In fact, there is a prologue before the main campaigns. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

One of my candidates is Tarentum, another is Syracuse and another is Agrigentum. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

gameplays Age of Empires 2 stuff

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Introductions & Off-Topic Discussion

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

It is supposed to start with a colony or expansion of a colony. you can start without the CC. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

Because we don't have any history with a shipwreck.It is supposed to have a historical background. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

Might work with AoE III deck + game stats. Stats determine the resources and the number of soldiers, which would be like a piggy bank. You could save the resources and the soldiers would remain in the form of cards. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

I imagined that it will be stored in the profile, as a statistic. Before starting, similar in AoE III and with the decks. (I didn't play battle for middle earth). @wowgetoffyourcellphone likes battle for middle earth. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

The topic of continuity is interesting and would be novel. Saving resources from one map to another, the difficult part would be transferring troops from one scenario to another. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

GUI ScrollPanel

Lion.Kanzen replied to trompetin17's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

Por fin alguien arreglo ese desastre con el árbol tecnológico. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

If we choose a story, it will happen on its own. But what if we do a poll? what colony will it be? If we start from the Mediterranean everything will be connected. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

I had exactly this in mind. The missions should be made diverse. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

You can start in nomadic mode with a large army. And then the locals(enemy) send in small waves of soldiers. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

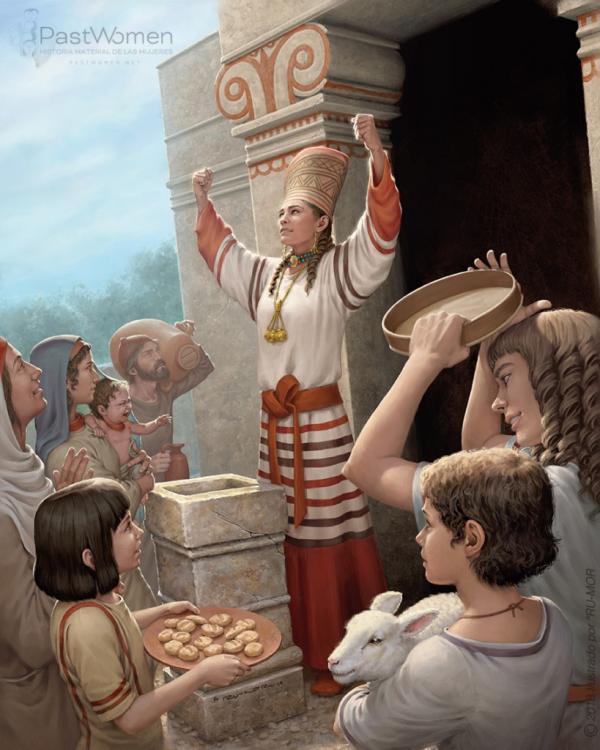

==[TASK]== Improved Carthaginian Priestess

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

About the goddess and their cult: I have found some new information and will do a quick review. Asherah (] Hebrew: אֲשֵׁרָה, romanized: ʾĂšērā; Ugaritic, romanized: ʾAṯiratu; Akkadia, romanized: Aširat;[3] Qatabanian: ʾṯrt)[4] was a goddess in ancient Semitic religions. She also appears in Hittite writings as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s) (Hittite: , romanized: a-e-ir-tu4),[5] and as Athirat in Ugarit. Some scholars hold that Yahweh and Asherah were a consort pair in ancient Israel and Judah,[6][7][8][9] while others disagree.[10][11][12] ----This as an introduction and review---- At that time, YHWH was the lord of the South and Baal was the lord of the North, according to Professor Jesús Mendoza. That is a minor but important detail to understand the Canaanite-Semitic pantheon. So Baal is the god of rain, which is important to people living in the desert, Asherah is the goddess of fertility, and YHWH was relegated to the god of war. The new thing I found is this: Queen of Heaven was a title given to several ancient sky goddesses worshipped throughout the ancient Mediterranean and the ancient Near East. Goddesses known to have been referred to by the title include Inanna, Anat, Isis, Nut, Astarte, and possibly Asherah (by the prophet Jeremiah). In Greco-Roman times, Hera and Juno bore this title. Forms and content of worship varied. ---It caught my attention that Isis is in that category.---- Isis was venerated first in Egypt. As per the Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, Isis was the only goddess worshiped by all Egyptians alike,[27] and whose influence was so widespread by that point, that she had become syncretic with the Greek goddess Demeter.[28] It is after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, and the Hellenization of the Egyptian culture initiated by Ptolemy I Soter, that she eventually became known as 'Queen of Heaven'. Astarte in the Levant and Egypt Regardless of how she was depicted in texts, archaeological evidence demonstrates her popularity throughout the Levant. She was worshipped in Baalbek, Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre, and in Baalbek, the chief city of Baal worship, she had more temples and shrines than he did. From the Levant it traveled along the trade routes to Cyprus, where it became equally popular, and the same is observed in Greece and Egypt. She arrived in Egypt during the 18th Dynasty of the New Empire (c. 1550-1292 BC) and is mentioned on the Sphinx Stele erected by Amenhotep II (r. 1427-1401 BC) as being "very pleased" with her handling of horses. Along with Anat, who traveled with her, she was considered the divine protector of the pharaoh in battle, specifically of his chariot and horses. She was understood to be the daughter of the god Ra (or maybe Ptah) and the consort of Set along with Anat. Her association with Set is explained in the popular story of The Confrontation of Horus and Set, a tale of the struggle of the two gods for the throne. The background to the action is the cycle of Osiris and Set in which the rightful king, Osiris, is murdered by his brother Set because of jealousy, is revived by his sister and wife Isis and his other sister, Nephthys, but because he is incomplete after the resurrection, he descends to the underworld to become the Judge of the dead. Isis raises her son Horus, and when he reaches maturity he challenges Set for the throne. In The Confrontation of Horus and Set, Horus and Set compete in the presence of a council of the gods to present their claim to the throne, and decide that they will have to settle their differences through a series of contests. Most of the gods believe that Horus should rule since he is the son of Osiris, but Ra believes that he is too young and inexperienced and that Set has the maturity to be a better king. These competitions drag on for 80 years, until Isis intervenes and convinces Ra, who grants the kingship to Horus. ----This divine council resembles that of the Semites---- https://www.worldhistory.org/astarte/ Other significant locations where she was introduced by Phoenician sailors and colonists were Cythera, Malta, and Eryx in Sicily from which she became known to the Romans as Venus Erycina. Three inscriptions from the Pyrgi Tablets dating to about 500 BC found near Caere in Etruria mentions the construction of a shrine to Astarte in the temple of the local goddess Uni-Astre [23][24] At Carthage Astarte was worshipped alongside the goddess Tanit, and frequently appeared as a theophoric element in personal names. Iconographic portrayal of Astarte, very similar to that of Tanit,[26] often depicts her naked and in presence of lions, identified respectively with symbols of sexuality and war. She is also depicted as winged, carrying the solar disk and the crescent moon as a headdress, and with her lions either lying prostrate to her feet or directly under those.[27] Aside from the lion, she's associated to the dove and the bee. She has also been associated with botanic wildlife like the palm tree and the lotus flower.[28] A particular artistic motif assimilates Astarte to Europa, portraying her as riding a bull that would represent a partner deity. Similarly, after the popularization of her worship in Egypt, it was frequent to associate her with the war chariot of Ra or Horus, as well as a kind of weapon, the crescent axe.[27] Within Iberian culture, it has been proposed that native sculptures like those of Baza, Elche or Cerro de los Santos might represent an Iberized image of Astarte or Tanit. ---I had no idea that I had arrived so early in Egypt.----- That explains all the iconography found in Spain. But that iconography did not reach the West.Neither in Greece nor in Rome did he arrive with wings or hats.