-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

all that are not Celts. Lusitanian, Edetani, Turdetani, Vettones. It is the only faction that we have not defined well. We are separating Lusitanias from the rest. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iberians

-

Spain + Portugal.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Cavalry archer turret mechanic

Lion.Kanzen replied to Yekaterina's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

Again its needed some patches (programming), there are already open tickets. @Stan` Get to know patches better. We have animation issues with mounted units. -

we need some code (patches) to allow to do that.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

=[TASK]= Roman Cataphract Horse Armor (2nd Century)

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Art Development

there would be several Roman factions later. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Minimap Icons

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Game Development & Technical Discussion

-

ironic is finding art of yours looking for things to make new things. https://aom.heavengames.com/downloads/showfile.php?fileid=11228 4 years after I made the faction symbol.

-

It seems to me that we do not have this animation, it should be reported as -missing-. But I must say that I don't know if the engine supports a reload animation like that. Or if it's convenient. @Stan`

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

===[TASK]=== Updated Cursors

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I meant the different actions. The truth was looking for the one from AoE I. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

===[TASK]=== Updated Cursors

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

-

But do we have to correct the weapon, I mean 3D model?

-

It would be useful to see how this weapon is used to shot. Animated, i.e. in motion.

-

Another thing I read, the Qin dynasty Bronze helmets were still used at this time.

-

Yikes.. We got the wrong weapon, apparently.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

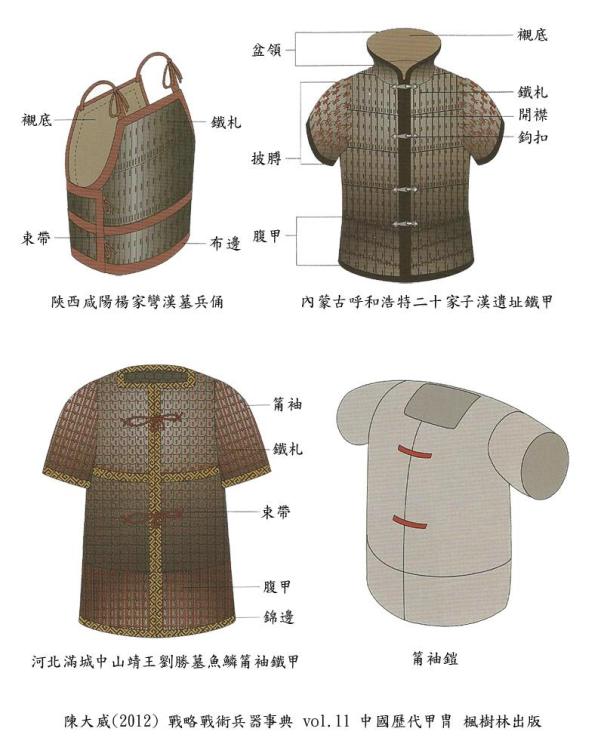

task [Task] Han Equipement (Armor, weapons, tools)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

No problem. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

task [Task] Han Equipement (Armor, weapons, tools)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

@AIEND Siege engines and weapons that you feel are missing? -

The armor looks good. Is it very impractical?

-

This one, I have a topic for many asian Factions. We have many fans of Asian cultures.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

task [Task] Han Equipement (Armor, weapons, tools)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

by the way we don't have a siege ram for Han. -

A new concept for me. I saw this in some Korean armor and some Kushans (Yuanzhi) armor.

-

you have to examples of these weapons?

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

===[TASK]=== Updated Cursors

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

The problem is that the current cursor has a good size and volume. It will be difficult to replace. The others are excellent. ------ there should be a cursor for attack move units only (control+Q click). Maybe a variant of current Control+ Click ( normal attack move).