-

Posts

25.684 -

Joined

-

Days Won

302

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

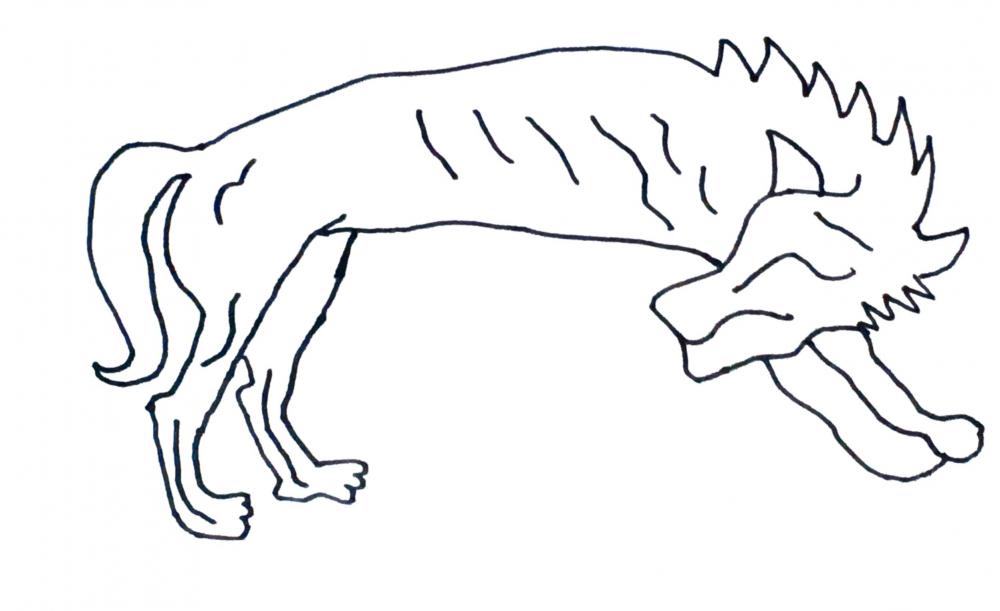

To be honest, just reference or avoid using any copyright. But only as a guide to improve our techniques or to inspire. With the she-wolf it didn't work for me using the AI that Jason used. With Rome as a goddess, it seems like an American Express, but that's the idea. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Increasing social media markting effort for 0ad visibility

Lion.Kanzen replied to Darkcity's topic in General Discussion

I'll try again with 0 AD in Spanish. I'm going to try to bring artists again. Additionally, I will be in art groups on FB and will bring new artists. In the past we brought people in from social media. -

https://techlandia.com/hay-manera-suavizar-lineas-lapicera-illustrator-como_304946/ Illustrator have a similar option. I draw using vectorial graphics, so I don't have to deal with pixels. It is always difficult and I also use my right hand to draw and not my left. I'm left handed.

-

Esto? No, ese dibujo lo hice a mano calcando desde la pantalla me servirá de base. Me da ganas de probar krita pero últimamente me gusta dibujar en el teléfono.

-

Estabilizador?

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[Brainstorming]== for cheats units

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Eyecandy, custom projects and misc.

- 198 replies

-

- brainstorming

- art

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

==[Brainstorming]== for cheats units

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Eyecandy, custom projects and misc.

It was deleted... https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Log?type=delete&user=&page=Jba_fofi&wpdate=&tagfilter=&subtype=&wpFormIdentifier=logeventslist- 198 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- brainstorming

- art

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I forget, you hate AI but you don't support art, you don't participate in the art forum. They don't support us much and then the rest of the art stagnates, nor do they give suggestions when you don't like it. -

-

-

-

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I need to find an aesthetic drawing that does not exist, how do I adapt the goddess Roma? AI gave me the ideas. It wasn't the only source material, but it provided the art didn't exist. the difference is very big. -

Today I have more time, I will try to do something today despite the physical fatigue from yesterday.

-

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

Nuclear energy is the future. Germany shut down its nuclear power and made Russian gas more expensive. Now Germany, the locomotive of Europe, is sinking. Solar panels and windmills are not going to save them from that. They destroy large natural environments for this. And worse... if they are damaged, they are not recyclable. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

If we didn't have low payments you wouldn't have cheap things. That is why all the production went to Asia, China became rich while the West sank. India and China are emerging from poverty thanks to this. I'm not complaining about a lower salary, the point is to have a salary rather than not to have one. But that's another topic. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

AI serves more as a teacher, it helps when there are mental blocks resulting from dedicating too many hours to something. It happens to me all the time, on this forum you will see that the works that did not make it to the game or some mod are my mental blocks. It's basically when all the initial inspiration is lost. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

Take screenshots of progress. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Narrative Campaign General Discussion?

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Gameplay Discussion

This I haven't been able to see it due to lack of time. I don't think I'll have time at Christmas, before and after as well. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

Interview by the Linux Professional Institute (LPI)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Stan`'s topic in Announcements / News

I hope so. It's one of Wow's favorites. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I don't think so. I don't think we'll have any artists for a while. Battle for Wesnoth It's not the same type of art required. We need to be more honest in the art department and put in some power. We need to make more noise on social media. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

I haven't started modifying them yet. I already said it above. If you can write we are not going to replace you with an AI. We've said that several times. We haven't even started using it yet. +++++++ I'll leave this here. I will use it as a tool to generate ideas. Not as 100% of my work. -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

Gracias -

.thumb.png.ce58cea22940c255f5b0a735d5abee36.png)

On the usage of AI to generate 0 A.D. content

Lion.Kanzen replied to wowgetoffyourcellphone's topic in Official tasks

.jpeg.5232e21079534e79dce0491bf5820123.jpeg)

.png.db54889a2617d1b1c0401e9b3bb22b1a.png)

.thumb.jpeg.10e4f563f42a6b649a826256d8f8dbc4.jpeg)