-

Posts

24.580 -

Joined

-

Days Won

272

Everything posted by Lion.Kanzen

-

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

==[Brainstorming]== for cheats units

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Eyecandy, custom projects and misc.

- 180 replies

-

- brainstorming

- art

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

Eurosasian Nomadic culture art.

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Tutorials, references and art help

Why not? That's much more complex than I thought,. I basically need new art references for Scythians and for the Xiongnu. In other words, it is more specialized than others. Do you have any other precedent? If I remember we don't have any patterns topic. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

Eurosasian Nomadic culture art.

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Tutorials, references and art help

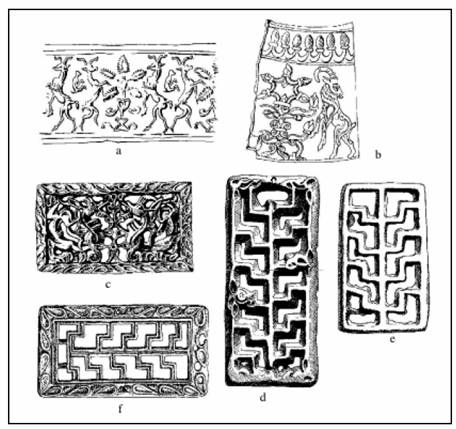

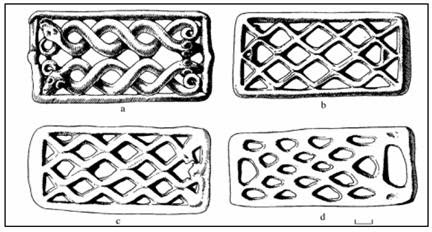

Xiongnu Art http://xiongnu.atspace.com/art.htm Introduction The so-called zoomorphic bronzes (plaques and buckles of various forms, buttons etc.) which display illustrations of various animals can be considered to be among the most impressive examples of Hsiungnu art. Examples of this artwork have been encountered in the Hsiung-nu sites of Trans-Baikalia, south Siberia , Mongolia and northern China . As a whole, there is no doubt that many of the images of Hsiungnu art, including the decorative bronzes, have parallels with the “Scytho-Siberian Zoomorphic Style”. Consequently, scholars have considered Hsiungnu art to be one of the developmental stages of this style. At the same time, however, a number of other Hsiungnu bronzes can be described using terms derived from a geometric style. These designs include “latticework” or “openwork” which can be found on belt plates, in addition to smaller artifacts including points and buttons. The origins of the geometric component of the art of the Hsiungnu are not entirely clear, since these objects do not find direct analogies among the Scythian cultures of Siberia and Central Asia . A detailed analysis of these artifacts has identified an evolutionary sequence which sees their origin in the zoomorphous “Scytho-Siberian” representations, most of which were strongly influenced by Near Eastern art. The objective of the following paper is to illustrate this origin through an examination of a number of pieces of the Hsiungnu geometric artwork. Buckle plaques for the upper belt of a dress It is possible to most clearly demonstrate the origins of “lattice-work” buckle plates. One of the most famous compositions of this style is a scene displayed on a gold plaque from the Peter the Great Collection, which displays fantastic animals standing beside a symbolic tree (Fig. 1c). The piece is encompassed by a rectangular frame, positioned on which are leaf-shaped pits for the inlay. The tree and the animals are well modeled, and the animal heads are quite realistic. It is probable that plates of this type were the prototypes for the manufacture of Hsiungnu bronze plaques, but during the course of repeated copying and re-casting many original details have been lost. The heads of animals, rendered in the same manner as those on gold plates from the Peter the Great Collection, are preserved in the frames of a number of bronze plates; probably the earliest examples of such objects. The composition as a whole at this stage, however, does not yet display evidence for a geometric interpretation. The frames of the plates become smoother, the branches of the tree disappear and it is transformed into broken zigzag lines combined with animal paws. These zigzags tie the frame of the plate to a direct line in the center of the piece which may depict the trunk of the initial symbolical tree in an extremely stylized manner (Fig. 1d). As a result of repeated reproduction, a stylization of the initial zoomorphic scene is apparent; the animal heads are now depicted by several pits, but eventually these pits also disappear. Consequently, the original scene depicting animals stranding beside a tree has developed into a geometric composition. The latest buckle plates have the appearance of trapeziums with zigzag edges and have little, if anything, in common with the original composition (Fig. 1e). The later craftspeople who moulded the buckles added a number of different details to the compositions in some cases including “foliage” on the framework of buckles which display “zigzags” (Fig. 1f ). It is probable, however, that by this stage the semantics and images of the initial scene were not clearly understoo -

-

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

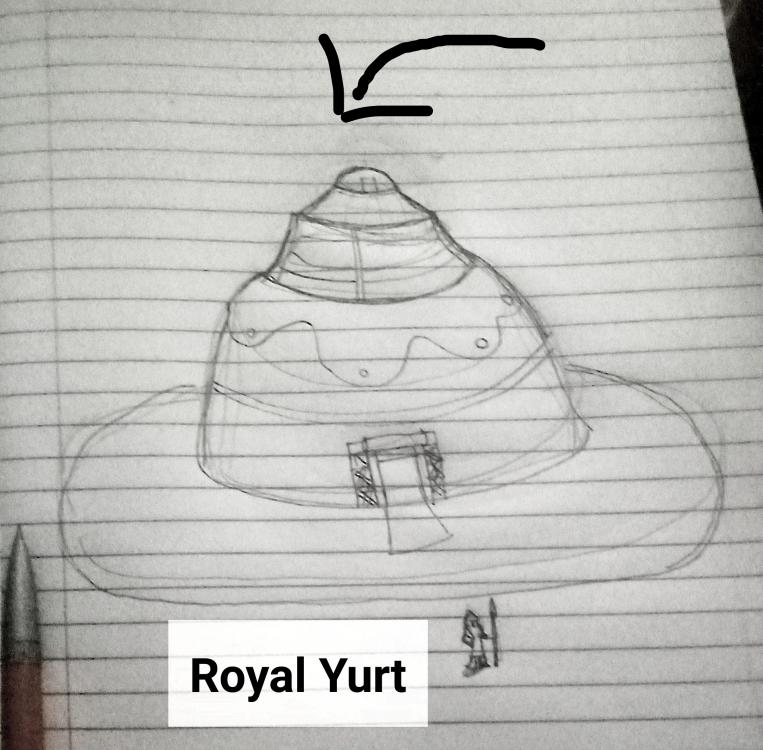

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

Yes, Xiongnu leaders used to use larger and more luxurious yurts compared to the standard yurts used by the majority of the population. These larger and more highly decorated yurts were reserved for the leaders and their families, as well as for important events and ceremonies. The leaders' yurts were often richly decorated with ornate fabrics, tapestries, carpets and other items that reflected their social status and power within the confederacy. Xiongnu leaders' yurts not only served as residences, but also functioned as centers of power and decision-making for the community. These structures highlighted the cultural, social and political importance of the leaders within nomadic society. Given the importance and status of the Xiongnu leaders, it is likely that they would have had special yurts designed for their use, with more luxurious and decorative features than the standard yurts used by the rest of the population. These "royalty" yurts would have served as residences and power centers for Xiongnu leaders, and are likely to have been larger, richly decorated, and equipped with additional luxuries. However, specific information on the royal yurts used by Xiongnu leaders may be limited due to the ancient nature of this civilization. Archaeological evidence, historical sources, and artistic depictions may provide clues about the appearance and use of these special yurts. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

Chat GPT about royal yurts. I decided to start with easy questions. Mongolian royal yurts were magnificent! They were much more than simple dwellings; they were symbols of power, status and tradition. These yurts were large and spacious, designed to house not only the Mongol leader, but also his court, guards and entourage. Compared to ordinary yurts, royal yurts were more luxurious and ornate. They were decorated with exquisite fabrics, furs and elaborate embroidery, often in bright colors. The interior of a royal yurt might include finely carved furniture, sumptuous carpets and other valuables. The design and layout of the royal yurt also reflected the hierarchical structure of Mongol society. There were designated areas for the leader, his family members, advisors and high officials, each with its own purpose and symbolism. In addition, the royal yurts were designed to be disassembled and transported quickly, allowing the Mongol leader to maintain his mobility during military campaigns and expeditions. This mobility was essential to the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols, as it allowed them to adapt to changing terrain and conditions. In short, royal yurts were impressive structures that reflected the wealth, power and unique culture of the Mongol leaders. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

I based myself on all these designs and on some 3D models. Obviously it needs more elements and props but this is the basic central idea. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

From the beginning I thought of it as one of the references I had, except that it is a Yurt (a circus/carnival tent, kind) much bigger than a simple tent, in theory the way it has been built with three levels: first a big gigantic tent then the second level of constructions a small tent of natural size and finally a kind of golden Dome maybe made of wood and bathed with gold or bronze. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

-

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[==Task==] Xiongnu Yurts Royal (textures and models)

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Official tasks

The main idea would be to brainstorm to create the original designs and base ideas. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

Art needed: remaining nomadic structures

Lion.Kanzen replied to real_tabasco_sauce's topic in Art Development

-

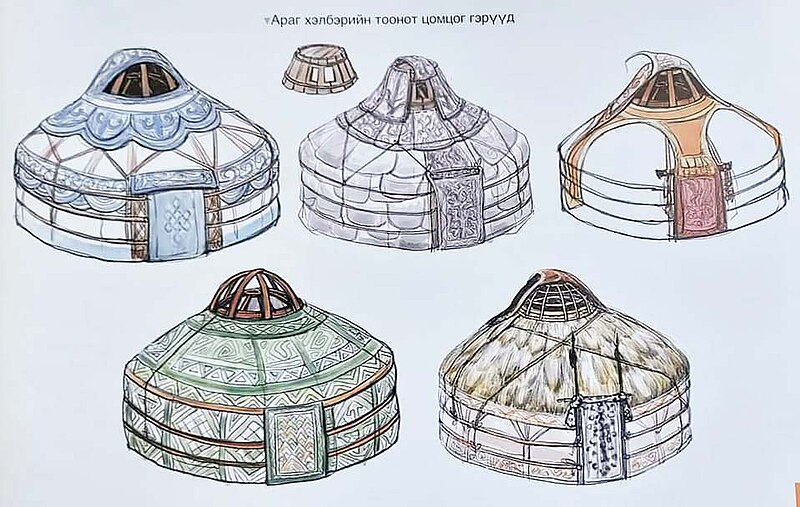

References for models (form) The shape, the props and the decorations. The decorations and the wooden door and the counter frame. Texture and colors.

-

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

Art needed: remaining nomadic structures

Lion.Kanzen replied to real_tabasco_sauce's topic in Art Development

I can try. I can start with research for a change or have enough variations. Then I draw. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

Art needed: remaining nomadic structures

Lion.Kanzen replied to real_tabasco_sauce's topic in Art Development

Are needed. New textures for this one, a prettier version. But I don't know how that would be historically correct. Patterns and symbols are needed for both cultures. It takes a lot of research and references. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[eye candy] Divine statues and myths.

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Tutorials, references and art help

In Hittite art, all weather gods, among them Teshub, were depicted similarly, with long hair and beard, dressed in conical headdress decorated with horns, a kilt and shoes with upturned toe area, and with a mace either resting on the shoulder or held in a smiting position.[59] In the Yazılıkaya sanctuary, Teshub is portrayed holding a three-pronged lightning bolt[e] in his hand and standing on two mountains,[37] possibly to be identified as Namni and Ḫazzi.[61] He is also depicted on a Neo-Hittite relief from Malatya, where he rides in his chariot drawn with bulls and is armed with a triple lightning bolt.[37 ------- To whom the descriptions refer quite a bit to themes that I have touched on such as The Sacred Bull. Edit2. Teshub was considered analogous to the Mesopotamian weather god, Adad.[102][15] A degree of syncretism between them occurred across northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia in the second millennium BCE due to the proliferation of new Hurrian dynasties, and eventually the rise of the empire of Mitanni, but its precise development is not possible to study yet due to lack of sources which could be a basis for case studies.[104] While Hurrian rulers are not absent from sources from the Old Babylonian period, they attained greater relevance from the sixteenth century onwards, replacing the formerly predominant Amorite dynasties.[105] As a result of this process, Teshub came to be regarded as the weather god of Aleppo.[79] However, as Semitic languages continued to be spoken across the region, both names of weather gods continued to be used across the middle Euphrates area. In Ugarit, Teshub was identified with the local weather god, Baal.[12] It is presumed that the latter developed through the replacement of the main name of the weather god by his epithet on the Mediterranean coast in the fifteenth century BCE.[115] In modern scholarship, comparisons have been made between myths focused on their respective struggles for kingship among the gods.[116] While Baal does not directly fight against El, the senior god in the Ugaritic pantheon, the relationship between them has nonetheless been compared to the hostility between their Hurrian counterparts, Kumarbi and Teshub.[117] Additionally, similarly to how Baal fought Yam, god of the sea, the Kiaše was also counted among Teshub's mythical adversaries, and both battles were associated with the same mountain, Ḫazzi.[118] However, myths about Baal also contain elements which find no parallel in these focused on Teshub, such as the confrontation with Mot, the personification of death, and his temporary death resulting from it.[117] In contrast with Teshub, Baal also did not have a wife, and in Ugarit Ḫepat was seemingly recognized as a counterpart of Pidray, who was regarded as his daughter, rather than spouse -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

[eye candy] Divine statues and myths.

Lion.Kanzen replied to Lion.Kanzen's topic in Tutorials, references and art help

Another Baal, Zeus equivalent. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teshub But this is Hittite-Hurrian. The iconography is similar to Baal. It must be said that the Hittites are quite related to the Greeks. So there are origins of some myths in the Hittite religion. -

.thumb.png.0d87fc71cb8a644c5d862ceabac1e0d5.png)

0 A.D. 2v2 Tournament (Team finding Thread)

Lion.Kanzen replied to DerekO's topic in Announcements / News

Again a spammer roachbot. -

About Manichaeism.

-

I was watching a video about the martyrdom of the Sassanids. The video is obviously in Spanish but I know that some very interesting conclusions regarding religion and also Parthians. The video talks about how the persecution of Sassanids was much more brutal than the Roman persecutions. The video says: Also that the Parthians were completely tolerant towards Christianity. And not only towards Christianity also towards Manichaeism. In fact, it was more intolerant to practice Manichaeism than Christianity. Christianity was well established in Western Persia. During the 2th and 4th centuries, the Church spread much deeper into Persia. On the other side of the map, in Rome, the harassment of Christians was generally of a local character, that is, it was confined to a region. But there were two major periods of persecution, which encompassed the majority of the population. regions at the same time. These are the ones that emperors Decius and Valerian. [...] was much closer to the Christian faith than Roman polytheism. Zoroastrianism was a dualistic religion centered on the conflict between good and evil, and there were superficial similarities with Christianity, such as the belief in a messiah and in the judgment after death. As a result, Christians did not emphasizei n Persian society as much as they did in the pagan society of the Roman Empire. The political situation in Persia changed radically at the beginning of the 1st century. The major invasions by Roman forces fueled a popular rebellion against the Roman The political situation in Persia changed radically at the beginning of the 1st century. The major invasions by Roman forces fueled a popular rebellion against the Roman peaceful Parthian dynasty. The Sassanids, a regime much more authoritarian, they won popular favor. with the platform of keeping Persia safe from the Romans and, in 224, they took control. The Sassanids were strict Zoroastrians they became of this religion the national faith of Persia. This period also saw the emergence of Manichaeism, another form of dualism, which competed directly with Persian religion. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martyrs_of_Persia_under_Shapur_II https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manichaeism

.png.d4530bab137daa46af7fda083abf92ce.png)

.jpg.75f8d4d4cef4b150676e37ba0f53a334.jpg)

.jpg.5640438607292380dc0d9d86d2f1cf77.jpg)

.png.7b25b485472d7e07b720531896d65fad.png)

.jpg.8c0cf8cbf966723ffa7f840f1e225e97.jpg)